Editor's Note, June 2021

Written by Marian Starkey, Vice President for Communications | Published: June 14, 2021

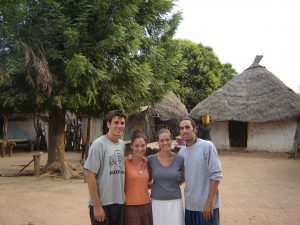

Just after finishing graduate school, and before looking for a job in my chosen field, I seized the life-changing opportunity to spend three months in Senegal, the westernmost country in the African Sahel region. I went with my husband, Alex, and a couple, Laura and John, who had become some of our closest friends during the time that Laura and I attended the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). Having both just gotten our masters degrees in Population and Development, we felt that it was important that we actually spend some time living and interning in a developing country—the decision to choose a francophone one was ambitious and probably ill advised, given that none of us were even close to fluent in French. (Oh, the enviable optimism of youth.)

We started out in a homestay about an hour north of the capital city of Dakar, attending daily French classes with a local eccentric on his rooftop and getting to know our neighborhood and playing with the children who screamed “toubab” (white person) every time they spotted us. We visited the beaches where the fishermen came ashore with their daily hauls, and where waiting women collected their catches to sell at the nearby markets. We attended a World Cup qualifier game in a stadium peppered with young police carrying machine guns. We sat around late into the night with our hosts’ neighbors, eating thiéboudienne (the national dish, which consists of fish, rice, and vegetables) with our hands out of the same large bowl, laughing about our cultural differences and trying to convince them that we were being truthful when we said we were full.

After leaving our homestay to live in an apartment in Dakar on our own for a couple weeks, we headed eight hours east to the inland town of Tambacounda, where Laura and I had secured internships with the NGO Africare. Our assignment was to visit remote villages in the region and talk with women about their health histories and barriers to access to reproductive health care, including family planning. Africare was considering setting up new health posts and wanted to make sure there was interest among these very rural communities in having a local clinic before getting to work on the process of creating one. In order to communicate with the women, Laura and I spoke in flawed French to a translator who spoke to the women in whichever of the three regional languages they spoke. The stories of loss we heard from these women were devastating. Many of them had lost babies and children to illness—some had lost more than one. And all of the women we talked with knew women who had died during pregnancy or childbirth or in the period shortly after. And yet, when we asked the women whether they would use contraception if they had a new health post in their village, it seemed as though many of them weren’t even sure what contraception was or how it could possibly prevent pregnancy. To be fair, this was 15 years ago, and I’m hoping that outreach to remote areas has improved since then.

As the Sahel region grapples with extremely high fertility and population growth, drought and other consequences of climate change, and entrenched poverty, the United States can (and should) help by scaling up its foreign assistance. The Biden administration is releasing its FY22 budget soon, but a preview of the numbers shows that the global health request is going to be $800 million higher than our current spending level. We hope that much of that increase will be directed toward international family planning programs, which the U.S. is underfunding by more than $1 billion, according to the commitment we made at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo. For the sake of women and girls in Senegal, in the entire Sahel region, and in all low- and lower-middle-income countries, it’s time that we make good on our pledge and provide the assistance needed to improve health and well-being and tackle global population challenges.

Marian Starkey

marian@popconnect.org