Population Education (PopEd) Found Its Feet 50 Years Ago

Written by Pamela Wasserman, Senior Vice President for Education | Published: December 8, 2025

In 2025, PopEd is the only remaining program of its kind in the United States, preparing educators to teach about human population growth and its effects on the environment and human wellbeing. But, in 1975, when Zero Population Growth (ZPG), the founding name of Population Connection, launched PopEd, universal, K–12 population education had the backing of state and national policymakers and teacher associations.

In 2025, PopEd is the only remaining program of its kind in the United States, preparing educators to teach about human population growth and its effects on the environment and human wellbeing. But, in 1975, when Zero Population Growth (ZPG), the founding name of Population Connection, launched PopEd, universal, K–12 population education had the backing of state and national policymakers and teacher associations.

This widespread support for teaching American students about population challenges existed thanks to the environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s. In 1970, 20 million Americans gathered for the first Earth Day to protest polluted air, river fires, and industrial chemicals poisoning wildlife and drinking water. The public outcry produced dramatic results. In rapid succession, Congress and the Nixon administration created the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and passed bipartisan legislation to ensure clean air and water, protect endangered species, and fund environmental education.

The Environmental Education Act of 1970 set up the US Office of Environmental Education (OEE) within what was then the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, to promote and fund environmental education programs, teacher training, and curriculum development. The Act defined environmental education as the “educational process dealing with man’s relationship with his natural and manmade surroundings, and includes the relation of population, pollution, resource allocation and depletion, conservation, transportation, technology, and urban and rural planning to the total human environment.”

Advisors to President Nixon went even further, specifically addressing the need for population education. The President’s Commission on Population and the American Future in 1972 proposed the passage of a Population Education Act to “assist school systems in establishing well-planned population education programs so that present and future generations will be better prepared to meet the challenge arising from population change.” While the recommendation was never taken up by Congress, it may have contributed to a growing interest in population studies. Five states (Delaware, Florida, New Jersey, New York, and Washington) acted on their own, mandating the development of teaching materials on population.

Major teacher organizations encouraged the inclusion of population education in school curricula, including the National Education Association, the American Home Economics Association, the National Association of Biology Teachers, and the National Council for the Social Studies.

Baltimore adopted population education as part of the social studies curriculum for all grade levels after hosting a series of well-received workshops for the city’s teachers. Those workshops and lessons became the basis of ZPG’s first teaching materials. In 1975, the OEE provided a grant of $27,216 to ZPG to begin conducting population education teacher workshops during the 1975–76 school year. Staff coordinated with state departments of education, university faculty, and environmental organizations to host one- and two-day training sessions for school principals and teachers in Delaware, Florida, Maryland, New Jersey, and Ohio. ZPG’s Population Education program was off and running.

A different approach for ZPG

While ZPG had previously published materials to educate the adult public, these were all part of the organization’s advocacy efforts to pass policies to stabilize global and US population. The new PopEd program needed to take a different approach, in line with best practices in “value-fair” instruction for K–12 students. That approach has been recommended by educational leaders for decades. We want students to use critical thinking skills and inquiry to guide their learning around population issues, rather than being told what or how to think.

Elaine Murphy, the first director of the program, explained in a 1978 issue of the ZPG National Reporter (the precursor to this magazine):

“Beyond political and legal reasons, there are philosophical reasons — based on beliefs about learning — for avoiding a preachy approach. […] I believe that long-lasting change comes from a person’s own involvement with issues, weighing information and research findings and finally integrating such learning into one’s own set of values. That is why ZPG workshops are blends of information and involvement activities that permit participants to draw their own conclusions.”

The scope of the curriculum would include activities to understand population dynamics, how people use finite resources and impact ecosystems, and the social and economic factors that influence population growth in different regions of the world.

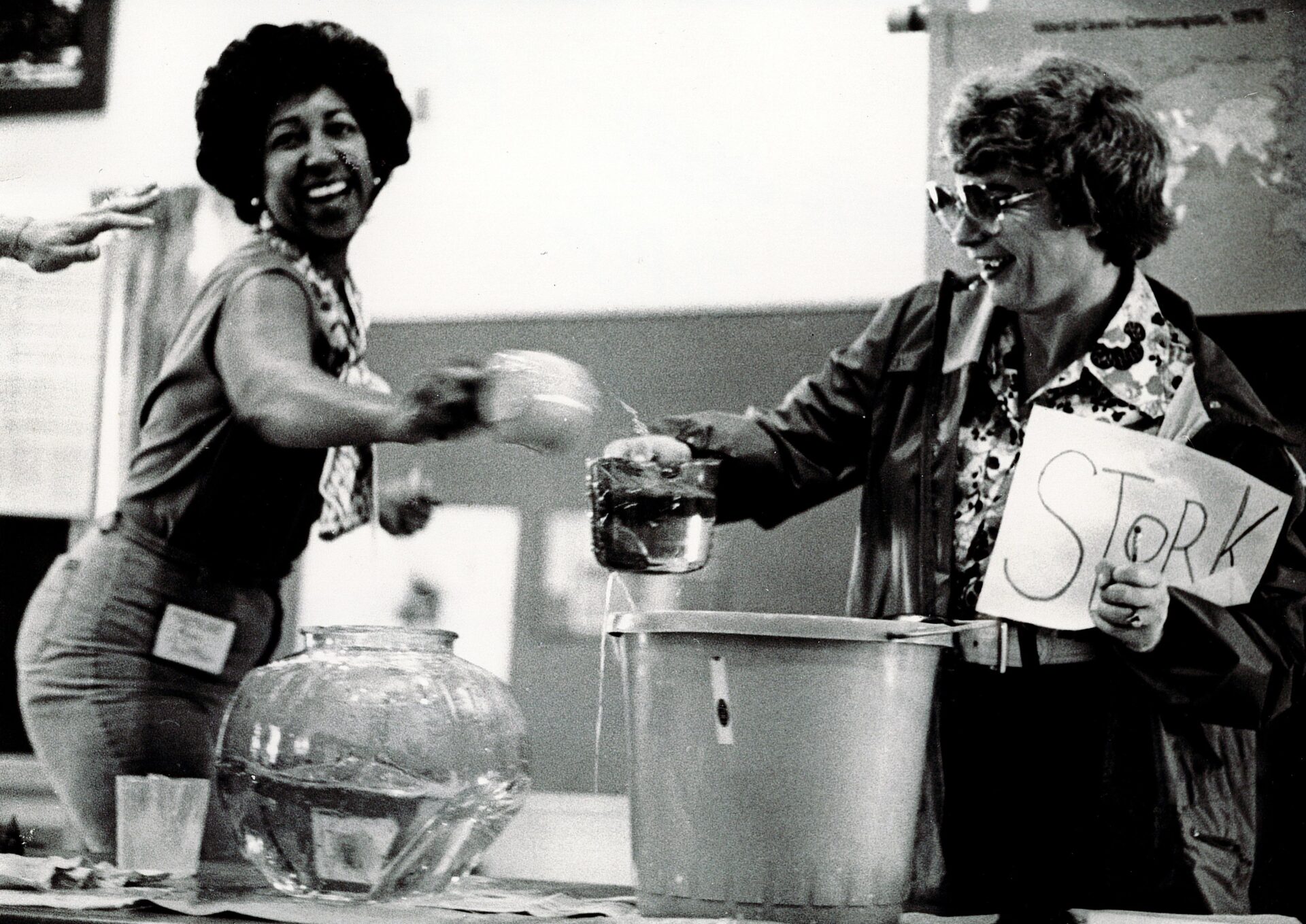

The ZPG Population Education Resource Kit, published in 1976, was PopEd’s first collection of teacher materials. It included math riddles to illustrate exponential growth and the magnitude of a billion (world population had just reached 4 billion). A global simulation game, Food for Thought, divided the class into world regions to compare data on population growth, wealth, health, energy use, and women’s roles. In The Stork and the Grim Reaper, students used different sized measuring cups and bowls of water to demonstrate how birth and death rates change the population. Those activities are all still in use today, along with a dozen more that have stood the test of time.

Sustaining PopEd

The OEE shuttered years ago, and experiments in mandated population education at the state level were short-lived. Fortunately, private funders (ZPG/Population Connection members and foundations) built on that very first government grant in 1975, enabling PopEd to continue developing curricula and hosting workshops. Over the last five decades, PopEd staff and volunteers have trained hundreds of thousands of educators, who have engaged tens of millions of students, in activities for a sustainable future.

A “Dot” Video for the Ages

Before there was even a PopEd program, there was World Population: A Graphic Simulation of the History of Human Population Growth, a short film developed by the ZPG chapter at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale.

Before there was even a PopEd program, there was World Population: A Graphic Simulation of the History of Human Population Growth, a short film developed by the ZPG chapter at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale.

Produced in 1972, the film showed the exponential growth of the world’s population since 1 CE, with the addition of stick-on dots on a world map, each dot representing 1 million people. The early stop-motion animation was powerful, especially with a soundtrack of a heartbeat, growing louder and faster as the population increased. At the time, the global population was approaching 4 billion people — less than half of what it is today.

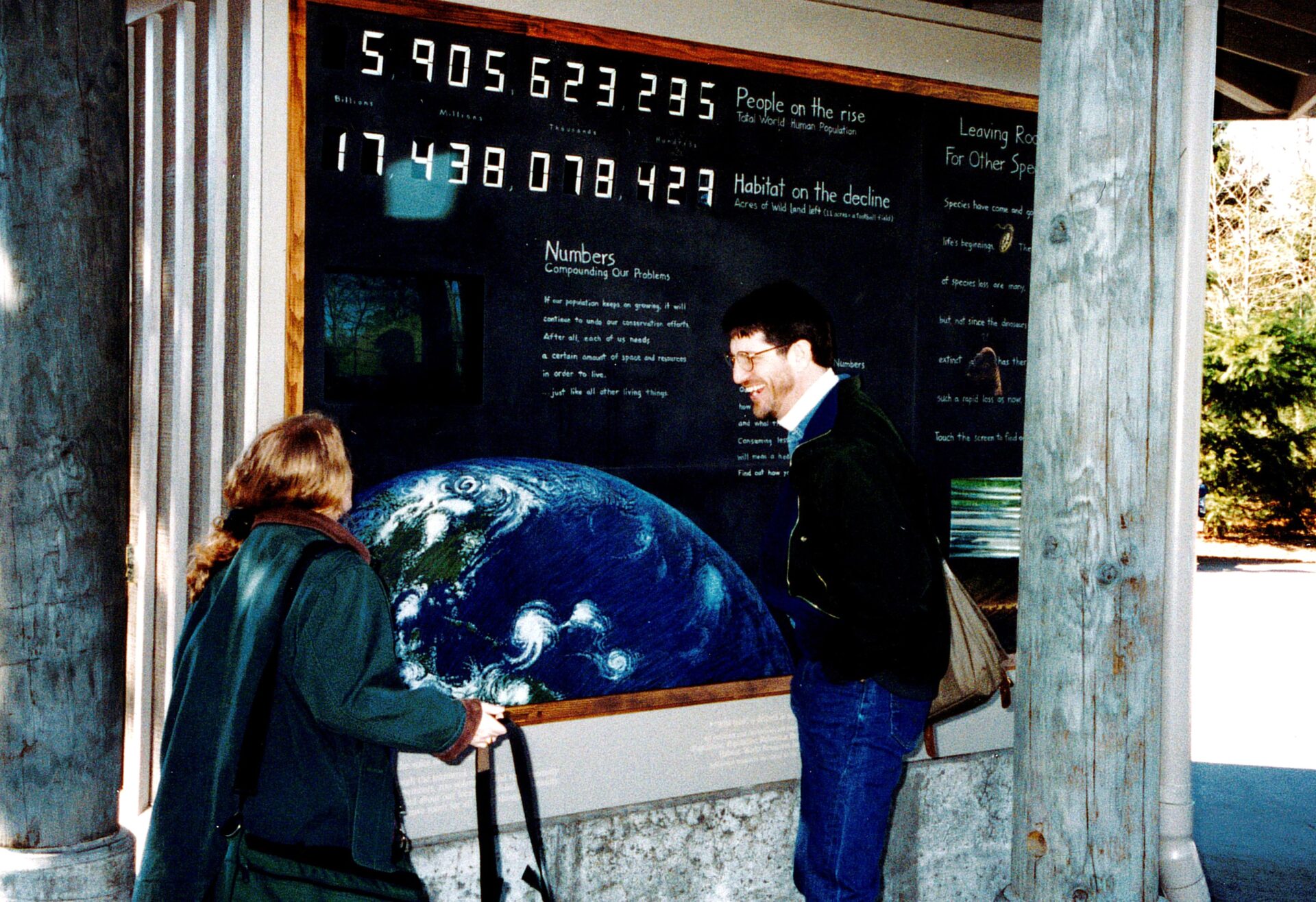

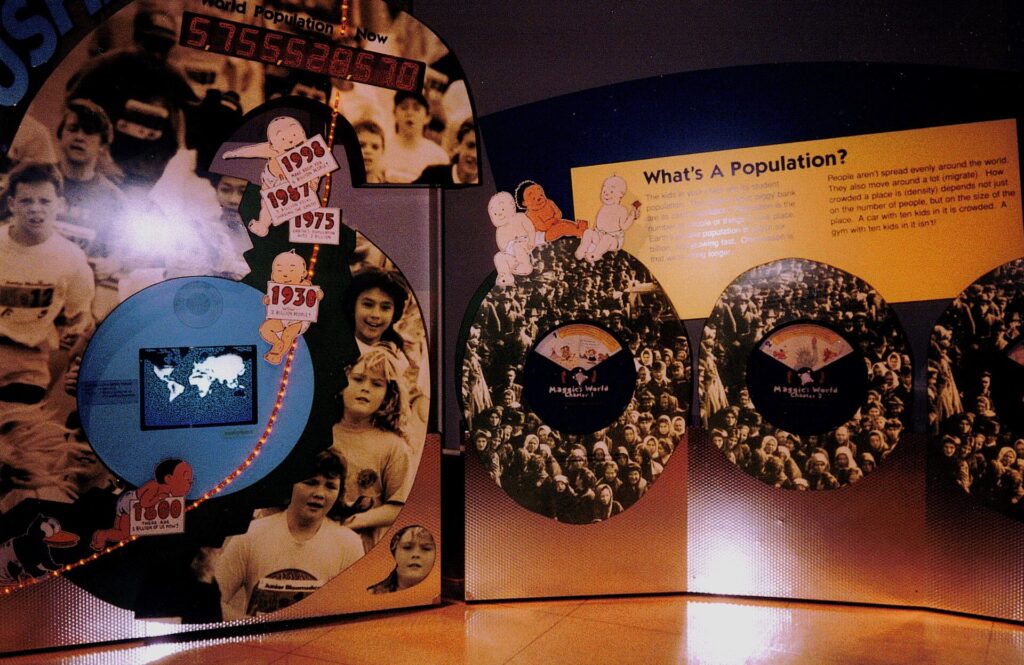

When ZPG launched PopEd three years later, the “dot video” became a staple of teacher workshops and was soon sold through school suppliers as a 16mm film. It remained on a film reel until our staff developed a new version for VHS in 1990. Global population had just surpassed 5 billion people, and the video projected a 2050 population of 8 billion (28 years later than the actual date that milestone was reached). In 1991, World Population took home the prize for Best Ecology Video from an international science film competition in Spain.

Over the next decade, the video’s use expanded beyond classrooms to reach a wider audience at museums and science centers around the world. These included a traveling exhibition hosted by the Smithsonian Institution and National Geographic, and permanent placement in the Hall of Biodiversity at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

The “millennium” edition of World Population was released in 2000, first on VHS, and later as a DVD. It was produced by Scott Vance, a graphic designer and longtime ZPG member, who also worked with Seattle’s Woodland Park Zoo to install the video in a new kiosk, linking population growth to habitat loss. Another Seattle landmark, the Starbucks headquarters, licensed use of the video for their new employee training.

Beginning in 2015, a new version streamed from its own microsite, WorldPopulationHistory.org. This edition was produced in multiple languages and is interactive, enabling site visitors to stop the animation at any point and learn more about the populations of different areas, from ancient civilizations to modern megacities. In 2019, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) added the video to its data visualizations playing on Science on a Sphere, a 6-foot, 3D globe with 175 locations around the world. And, of course, it’s still viewed in thousands of classrooms every year.

Beginning in 2015, a new version streamed from its own microsite, WorldPopulationHistory.org. This edition was produced in multiple languages and is interactive, enabling site visitors to stop the animation at any point and learn more about the populations of different areas, from ancient civilizations to modern megacities. In 2019, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) added the video to its data visualizations playing on Science on a Sphere, a 6-foot, 3D globe with 175 locations around the world. And, of course, it’s still viewed in thousands of classrooms every year.

Plans are underway for a new update to be released in 2027.

Pam Wasserman: pwasserman@populationeducation.org