China's population has peaked — that's good news

Written by Olivia Nater | Published: January 20, 2023

The country with the largest population for the past 300 years, now home to 1.4 billion people, has officially begun shrinking, according to new demographic data. Many media outlets are painting this development as a potential disaster — it isn’t. Rather, it represents a necessary transition to a more sustainable future.

The news

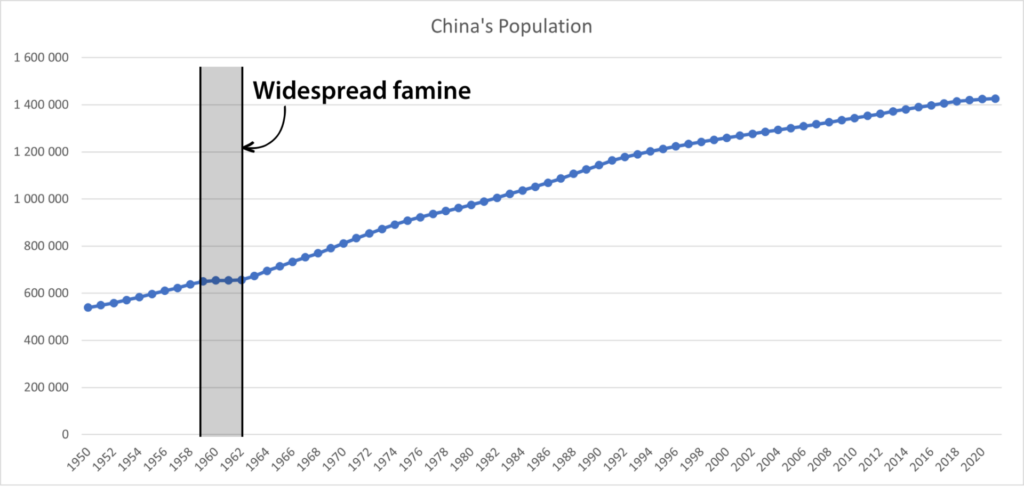

On Tuesday, China’s National Bureau of Statistics announced that its population declined by roughly 850,000 people between 2021 and 2022, the first shrinkage since the 1960s. This was not unexpected — according to UN data, China’s fertility rate (the average number of children per woman) dropped below two back in 1991 and now stands at only 1.2.

If the Chinese data are accurate, it means India may now be the most populous country, by just a few million. To be clear, China’s population is nowhere near collapse — the UN projects a gradual decrease, to 1.3 billion in 2050.

Demographic background

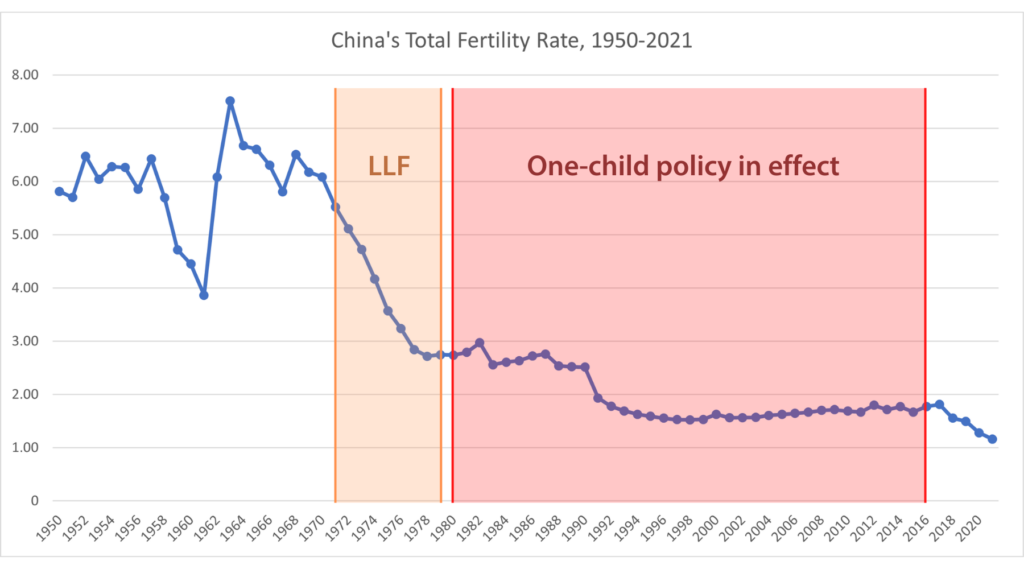

China has a rocky demographic history. Its infamous coercive one-child policy, in effect between 1980 and 2016, contributed to the decline in average family size, but it had a much smaller effect than many believe. The policy was a human rights violation, resorting to forced contraception and abortion, as well as economic sanctions for non-compliance, and resulted in a skewed sex ratio due to sex-selective abortion and female infanticide. It was also wholly unnecessary. China’s fertility rate began shrinking dramatically well before the one-child policy was enacted, as a result of a non-coercive “Later, Longer, Fewer” campaign encouraging a later start to childbearing, greater spacing of births, and smaller family size.

The Later, Longer, Fewer (LLF) policy, introduced in 1971, was precipitated by a national disaster in which, following rapid population growth and severe disruptions to China’s agriculture under Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward campaign, an estimated 20 million people died of starvation between 1959 and 1962.

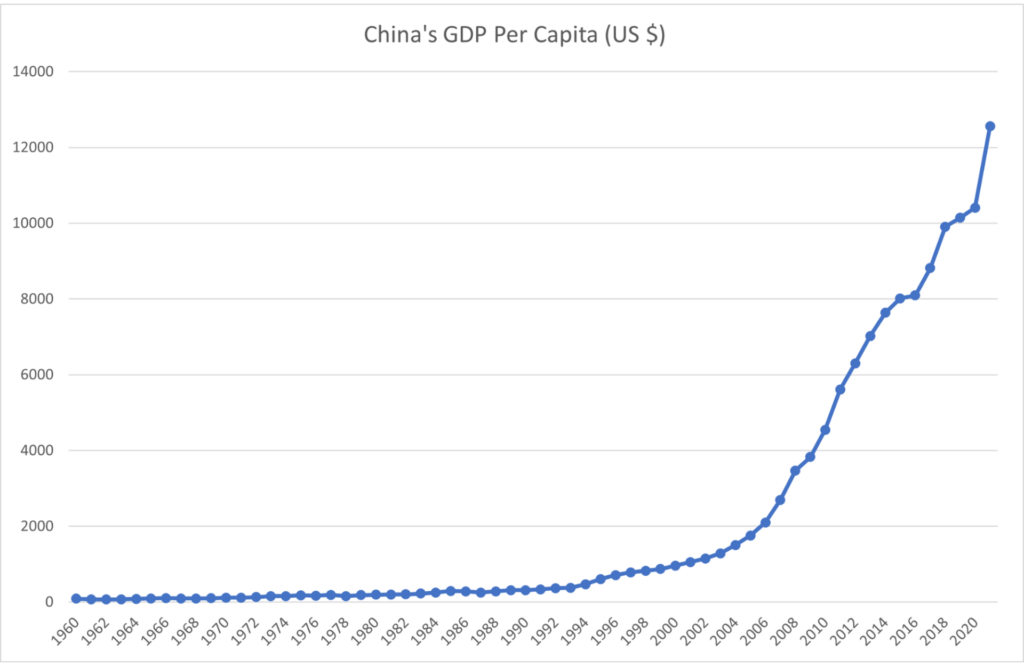

Slower population growth due to the LLF campaign helped alleviate food shortages and also fueled China’s economic development as couples with fewer children had more disposable income and more women were able to join the workforce.

With the fertility rate continuing to drop, however, the government began to worry about rapid population aging, a shrinking labor force, and economic stagnation. In 2016, the one-child policy was replaced with a two-child policy, and in 2021, the two-child limit was scrapped for a rather ludicrous three-child policy (instead of just removing restrictions on family size). This was accompanied by strong propaganda from the Communist Party promoting childbearing, as well as incentives such as tax deductions, longer maternity leave and housing subsidies. These measures have had no significant effect on the birth rate.

People want small families

The fact is, low fertility rates are here to stay — across the world, once women gain the power to use modern contraception and to pursue education and careers, they choose to have fewer children, on average. Raising many children is not only expensive but limits parents, especially mothers, in countless other ways.

A 33-year-old photographer in Beijing told The New York Times that she and her partner have embraced the “Double Income, No Kids” lifestyle, stating she “never had the desire to have children all along.”

Declining birth rates are a symbol of women’s emancipation and should be celebrated, not feared. This applies not only to China but to the many other countries that are trying to reverse this positive trend because of economic worries. The latter are often overblown — an older, shrinking population is still able to thrive.

Unjustified fears

Thanks to medical advances, people past retirement age are staying healthier and are able to contribute to society in multiple ways, from extending their working years, to providing childcare, to volunteering. We have proof that population aging and decline do not spell economic doom and societal collapse. Japan is an extreme example — its population is rapidly aging and has been shrinking since 2010. Despite this, the country’s GDP per capita has remained largely the same since the early 1990s, while its purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita is still increasing. Japan also ranks higher than the U.S. for quality of life.

Thanks to medical advances, people past retirement age are staying healthier and are able to contribute to society in multiple ways, from extending their working years, to providing childcare, to volunteering. We have proof that population aging and decline do not spell economic doom and societal collapse. Japan is an extreme example — its population is rapidly aging and has been shrinking since 2010. Despite this, the country’s GDP per capita has remained largely the same since the early 1990s, while its purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita is still increasing. Japan also ranks higher than the U.S. for quality of life.

Investing in preventive healthcare goes a long way towards reducing the burden of care for elderly citizens, while technological innovation can mitigate impacts of a shrinking labor force. Countries that are desperate to rejuvenate their populations could also welcome more young immigrants fleeing from areas where rapid population growth is outstripping already fragile infrastructure and services.

Environmental benefits

Reports on population decline also tend to neglect the enormous environmental gains this brings. At 8 billion and counting, and in the midst of escalating climate change, biodiversity loss and natural resource depletion, the last thing our overburdened planet needs is more growth.

China’s status as the most populous country (or perhaps second most populous now), and second largest economy (after the United States), makes it one of the worst culprits of environmental degradation. For example, China is the world’s biggest national emitter of greenhouse gases — a continuously growing Chinese consumer base, with increasing per capita consumption, is incompatible with global climate targets.

China’s growing food demand alone, especially for meat and dairy, is cause for concern. It is the largest country-level producer and consumer of meat, especially pork. The large number of livestock raised for meat requires a huge amount of feed — China is the biggest importer of soybeans globally, the cultivation of which is closely linked to deforestation, especially in the Amazon Basin. A 2019 report found that 43% of 2017 deforestation emissions from soybean cultivation in Brazil could be attributed to imports into China.

China’s growing food demand alone, especially for meat and dairy, is cause for concern. It is the largest country-level producer and consumer of meat, especially pork. The large number of livestock raised for meat requires a huge amount of feed — China is the biggest importer of soybeans globally, the cultivation of which is closely linked to deforestation, especially in the Amazon Basin. A 2019 report found that 43% of 2017 deforestation emissions from soybean cultivation in Brazil could be attributed to imports into China.

China’s role as a manufacturing hub for cheap, mass-produced products that are shipped around the world also takes a huge toll in terms of air, water and plastic pollution, as well as human rights abuses (although the blame lies just as much with the countries that create the demand for these products).

Degrowth is the future

Gradual population decline as a result of small family size becoming the norm is the best outcome we can hope for on our finite planet. Infinite growth, on the other hand, can only lead to disaster.

As Chinese politics specialist June Teufel Dreyer told the Associated Press,

“It amazes me how everyone seems to agree that the planet already has too many people whose demands for even the basics of existence like food, water and shelter are placing intolerable demands on the ecosystem — yet as soon as the population of a country begins to decline, its government reacts with near panic.”

Not to mention that all this fearmongering is fueling reproductive rights violations. In Iran, for example, public healthcare providers are now banned from offering free contraception, and voluntary sterilization is prohibited, alongside increasingly draconian abortion restrictions. Human rights advocates fear that China too may once again resort to coercive measures.

China’s demographic downturn is reason for hope, not a crisis. It is not the first country to go through this transition, and many others will follow. Let us embrace degrowth as a necessary pathway towards a more sustainable future in which human well-being and a safe environment are valued more than short-term profits.