California's Catastrophic Wildfires in Three Charts

Written by Article by Isabella Isaacs-Thomas | Charts by Megan McGrew | Published: December 14, 2020

Originally published by PBS on September 14, 2020

The devastating wildfires tearing across California, Oregon, Washington, and several other Western states are an increasingly familiar scene, as blazes have become larger and more destructive over the past several decades.

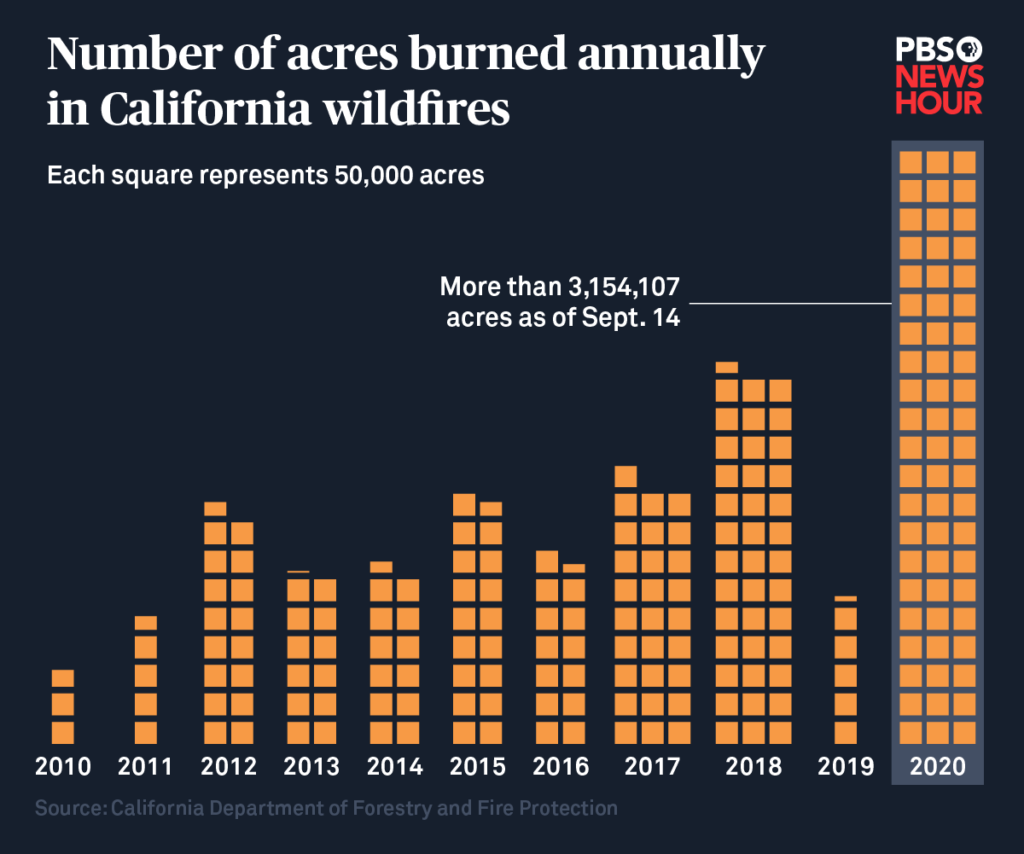

Seven of the top 10 most destructive fires in California’s history have occurred since 2015, and this year’s fires have already burned an unprecedented 3.1 million acres in that state so far, driven in part by lightning storms and an extreme heat wave.

The autumn winds that typically fuel the bulk of destruction during California’s wildfire season have already begun to blow, contributing to dangerous conditions like low humidity and dry vegetation that have helped fuel fires including the yet-uncontained August Complex, now the largest fire in California history.

Meanwhile, about 10 percent of Oregon’s population were placed under some level of evacuation notice last week, and although wildfires burned more slowly in that state over the weekend, smoke created unhealthy to hazardous air quality that is forcing residents across that state and the broader Pacific Northwest to stay inside. At least 35 deaths have been confirmed across California, Washington, and Oregon, and officials have said the toll is expected to grow.

Annual wildfires occur naturally in multiple states, but highly populated California has a lot to lose when fires burn widely and out of control. A 2019 report from the company CoreLogic found that California’s metropolitan areas “dominate” a list of the top 15 regions most at risk for wildfire damage, due to its “high density of homes located in wildfire-susceptible areas.”

Given the ongoing destruction, oppressive air, and ominous skies turned orange by the smoke, many are once again drawing a connection between the changing climate, extreme weather events, and wildfire season. As the planet continues to warm, experts predict that droughts and heat waves—both factors that paved the way for this year’s catastrophic fires—will only intensify with time.

The effects of climate change are already being felt, but that’s not to say that a future marked by regular, widespread devastation of communities and ecosystems, in addition to loss of life, is completely unavoidable.

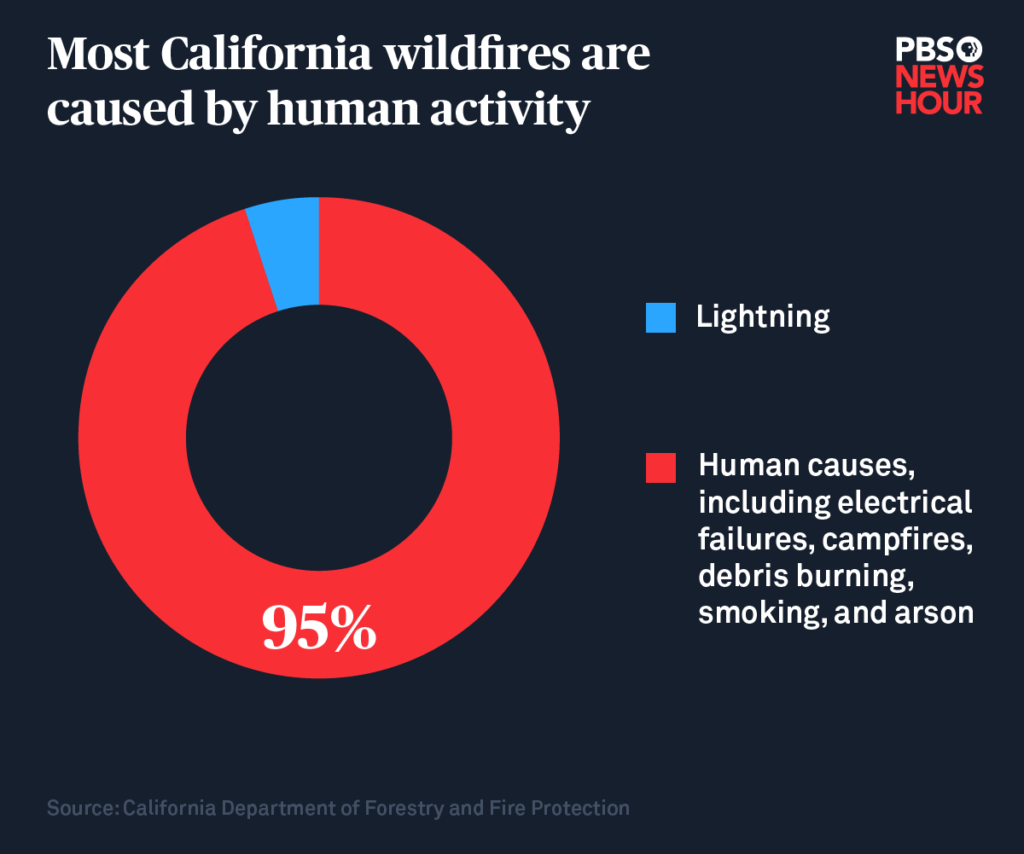

Ninety-five percent of wildfires in California are caused by human activity. Although we can’t control the yearly winds that fuel those fires in the fall, or the droughts that regularly choke the region, we can address the daily human decisions that have a direct impact on how and why wildfires break out in the first place.

Here are three charts to help you understand those fires, and what experts say we need to keep in mind if we want to reduce the risk of future disaster.

For a sense of how wildfire season is worsening in California, Lynne Tolmachoff, who serves as chief of the CalStats program at the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire), points to how long that season lasts now, compared to previous years.

When Tolmachoff started at CalFire two decades ago, seasonal firefighters were expected to work about five months out of the year, from around mid-July to early October. Now, she said, some firefighters are working as many as nine months out of the year, as the season has begun to start earlier and end later than it has in the past.

“Now we’re seeing it starting in May and going occasionally into November, and even a couple years ago, we had to go into December,” Tolmachoff said. “Sometimes, Southern California, depending on what happens with their weather patterns, may never even go out of fire season. They may have to stay staffed, because they’re seeing wildfires year-round.”

This year’s fires, which have already broken state records in terms of total acres burned, were largely caused by the more than 14,000 lightning strikes that hit California during the month of August in combination with severely dry conditions. Although lightning accounts for just 5 percent of wildfires in California, Tolmachoff said the fires it sparks tend to burn more acreage than those caused by humans.

That’s due in part to where lightning tends to strike—usually, in mountainous regions with high elevations where, if a fire does start, it can be harder to contain due to the inaccessible nature of the terrain. “Dry thunderstorms” occur when storms cause thunder and lightning, but most or all of their precipitation never actually reaches the ground, allowing flames to smolder.

A similar phenomenon occurred back in 2008 when a severe thunderstorm system in Northern and Central California caused more than 6,000 lightning strikes that met “record dry conditions” and sparked more than 2,000 fires, according to CalFire. At the time, that season was considered to be one of the most severe on record.

What has made 2020 unusual, Tolmachoff noted, is the fact that the lightning struck not just the mountains, but also flatland areas and parts of the state that are more populated. Two complexes, or groups of fires, caused completely or in part by lightning strikes in the Bay Area this year have already been named two of the 10 most destructive fires in California history.

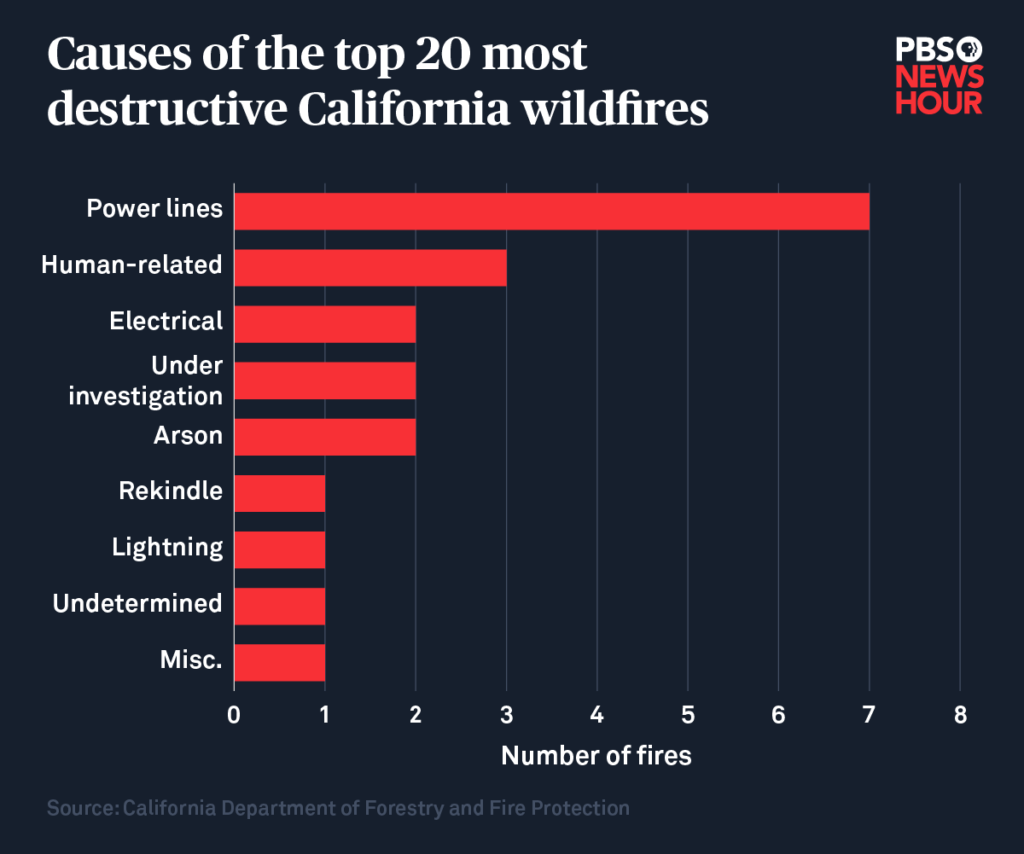

Although lightning fires cause immense damage, they account for just a fraction of the annual wildfire devastation in California during most years. The rest is caused by human activity and infrastructure like arson, power lines, and, recently, the use of a pyrotechnic device at a gender reveal party, which sparked the yet-uncontained El Dorado fire that began in early September.

This year’s heat wave—in addition to years of intense drought—has made California’s dried out vegetation particularly effective fuel. Annual fall winds may continue to exacerbate this already disastrous fire season—a possibility Tolmachoff is particularly concerned about. When humidity is low, even when temperatures cool down, those wind gusts can both fan fires and spread them into different areas, historically bringing the “largest, most devastating fires.”

“Until we get some significant rain, we will remain in fire season. Even if the temperatures cool, we’ll still see fire,” Tolmachoff said. “So that’s probably our biggest concern, is the fact that we’ve already burned over [3 million] acres and yet we still have probably two good months at least of fire season to go.”

The infamous 2018 Camp Fire, which killed 85 people, was caused by “electrical transmission lines owned and operated” by the utility company Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) and exacerbated by the usual fire-friendly forces of dry vegetation, low humidity, and strong winds. That year’s fire season held the title of the most destructive on record until this year unseated it, and it’s still considered the most deadly.

Jon Keeley, a research scientist with the United States Geological Survey, noted that the major, multi-year drought that hit California between 2011 and 2019 killed off an immense amount of vegetation in the state. He said that more than a million trees in the Sierra Nevada died over the course of that drought, providing ideal fuel for the fires that are devastating that region now.

Keeley acknowledges that climate change “almost certainly” exacerbates fire-friendly conditions in California, but says that’s only part of the story.

The landscape varies widely across California, and different parts of the state have different terrain and conditions that can sustain wildfires. But one thing that remains constant is the fact that humans are responsible for the vast majority of the blazes that occur every year. Keeley argues that the role of human activity should be emphasized when it comes to addressing root causes of massive wildfires, and points to both the practice of fire suppression and California’s increasing population as primary factors.

“The bottom line is this is a multifactor problem. It’s not just climate change, it’s not just the drought, it’s not just dieback. It’s management activities that have suppressed fires for over a century—a lot of things going on,” Keeley said. “The way I see the current situation in California, this is the perfect storm. Everything is coming together at once.”

While this summer’s fires were fueled by lightning storms in addition to human activity, Keeley noted that the fires fueled by yearly autumn winds are “always” started by people, whether by accident or on purpose. He said that power line failures have been responsible for the majority of large-scale fall fires in the state over the past two decades.

Inadequate maintenance is partly to blame, courts have found. According to The New York Times, PG&E’s electrical network—which serves approximately 16 million people in Central and Northern California—has been linked to multiple destructive fires, and regulators have determined that the company “violated state law or could have done more to make its equipment safer” in several cases.

Power grids have also expanded to accommodate growing communities in the state, creating more opportunity for disaster. Keeley emphasized that California’s population has grown by 6 million since the year 2000.

“That 6 million increase in population means more people pushed out into areas of urban sprawl, of dangerous fuels, increased ignition sources, increased potential for people getting killed, an increase in the electric grid,” Keeley said. “So if there’s anything that can explain the increase in fires in the last 20 years, my feeling is it’s population growth.”

In addition to infrastructural issues like power grids, mitigating human error on an individual level is key to preventing future disaster. That’s why one of CalFire’s goals is to educate as many Californians as possible about how wildfires work, what causes them, and the fact that they can affect communities in any part of the state—urban, rural, or anything in between.

This year’s wildfires aren’t the only natural disasters or extreme weather events to devastate communities over the past several months, renewing attention on the global need to mitigate the growing climate crisis. But given the magnitude of that task, in the context of the California wildfires, Keeley argues that looking toward tangible, human solutions to human-caused problems can offer some degree of hope.

“It’s a positive view that we don’t just have to feel like we’re doomed to climate change,” Keeley said. “We can change our outcomes, in part due to how we deal with these situations.”