Demographic Delusions: Interview with Dr. Jane Nancy O’Sullivan

Written by Marian Starkey | Published: December 11, 2023

“Population Change and Its Impact on the Environment, Society, and Economy” is the title of a recent special issue of the academic journal World, edited by Drs. Jane O’Sullivan and Céline Delacroix. The articles, by researchers from Australia, Canada, Europe, South Africa, and the United States, are open access, so anyone can read them without having a subscription to World. Population Connection members with an interest in demography and a curiosity about how population is discussed in scholarly settings can take a look at the special issue here.

Dr. O’Sullivan co-wrote one of the papers, “Advancing the Welfare of People and the Planet with a Common Agenda for Reproductive Justice, Population, and the Environment,” with a former Chair of our Board of Directors, Dr. J. Joseph Speidel. She authored another paper on her own, “Demographic Delusions: World Population Growth Is Exceeding Most Projections and Jeopardizing Scenarios for Sustainable Futures,” questioning the assumptions the major demographic agencies and institutions make in their population projections. That paper is the subject of the following interview.

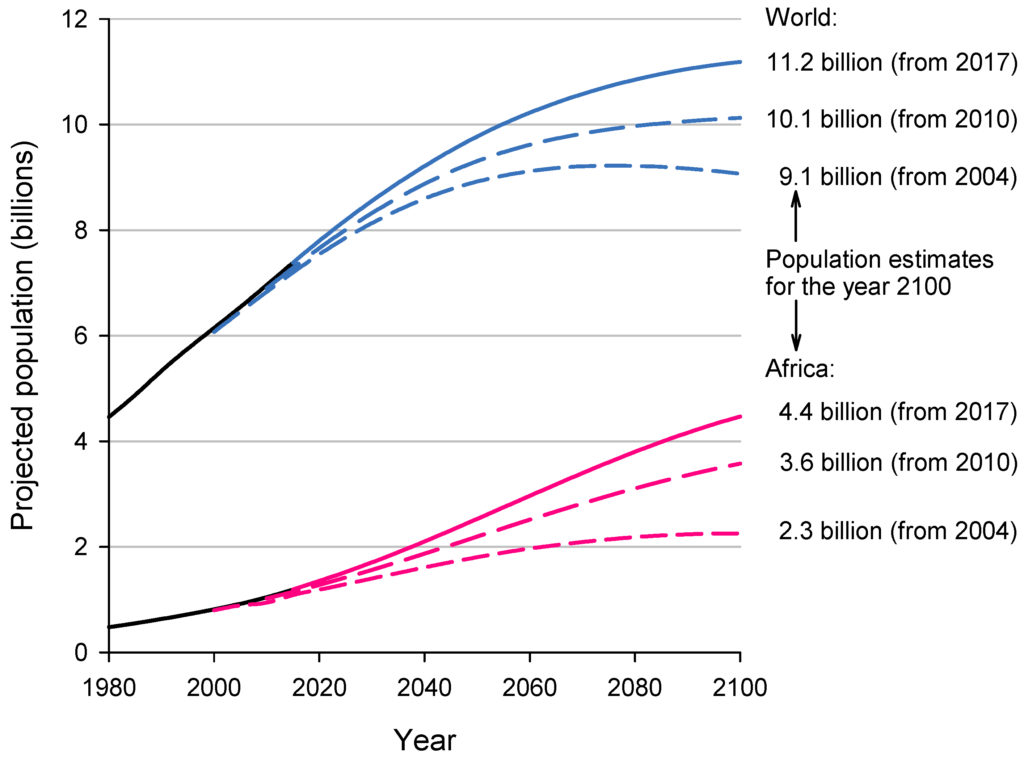

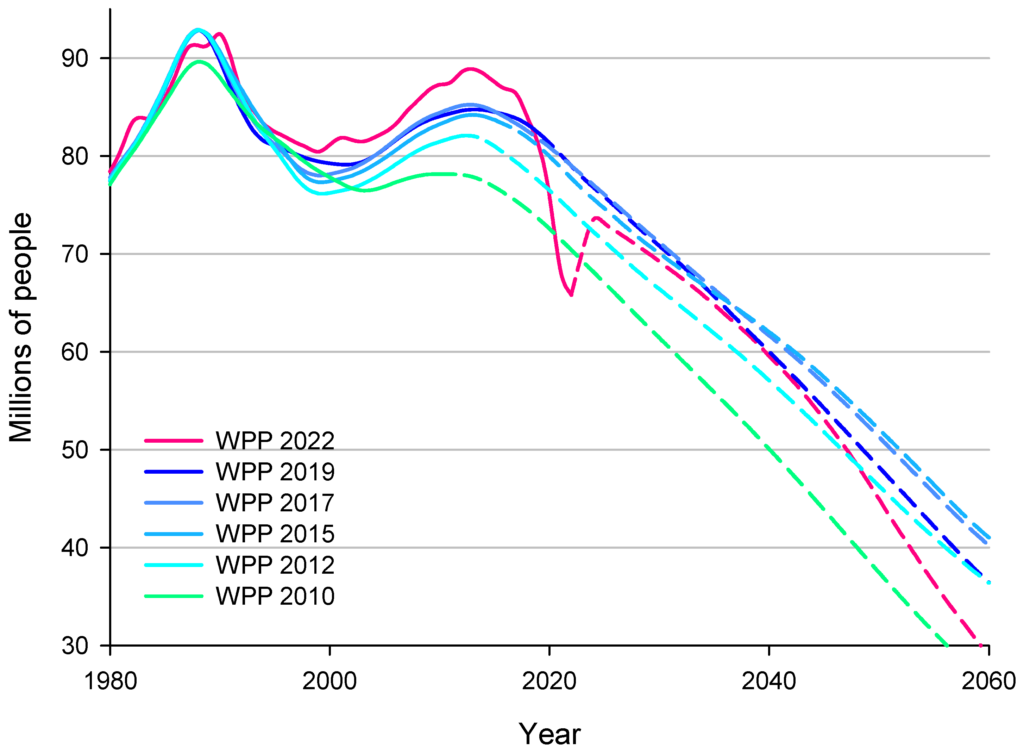

In her paper, Dr. O’Sullivan argues that the future fertility assumptions demographers have made in each new revision of the UN’s population projections over the past two decades have been unrealistically optimistic given recent trends in high-fertility countries. Demographers model future population growth assuming birth rates will decline in the remaining high-fertility countries the same way they did in countries that were early adopters of family planning decades ago. But with each new revision, the data show that this is not happening. And yet, UN demographers continue to make projections using the same optimistic assumptions. Dr. O’Sullivan rhetorically asks: “Is it reasonable to project the future to diverge so dramatically from the recent past?”

She argues that “model-forcing” has led demographers to underestimate future population size time and again, which Dr. O’Sullivan partially blames for the “population complacency” that prevents those in a position to effect change from making policy decisions that would voluntarily lower birth rates and thus slow population growth, speed economic development, and arrest environmental damage. She writes, “[Family planning] is no panacea for the environmental crises our crowded world now suffers, but it is an indispensable ingredient in any sustainable future.”

Please enjoy the interview. The endnotes are mine, added for reader clarity. –Marian

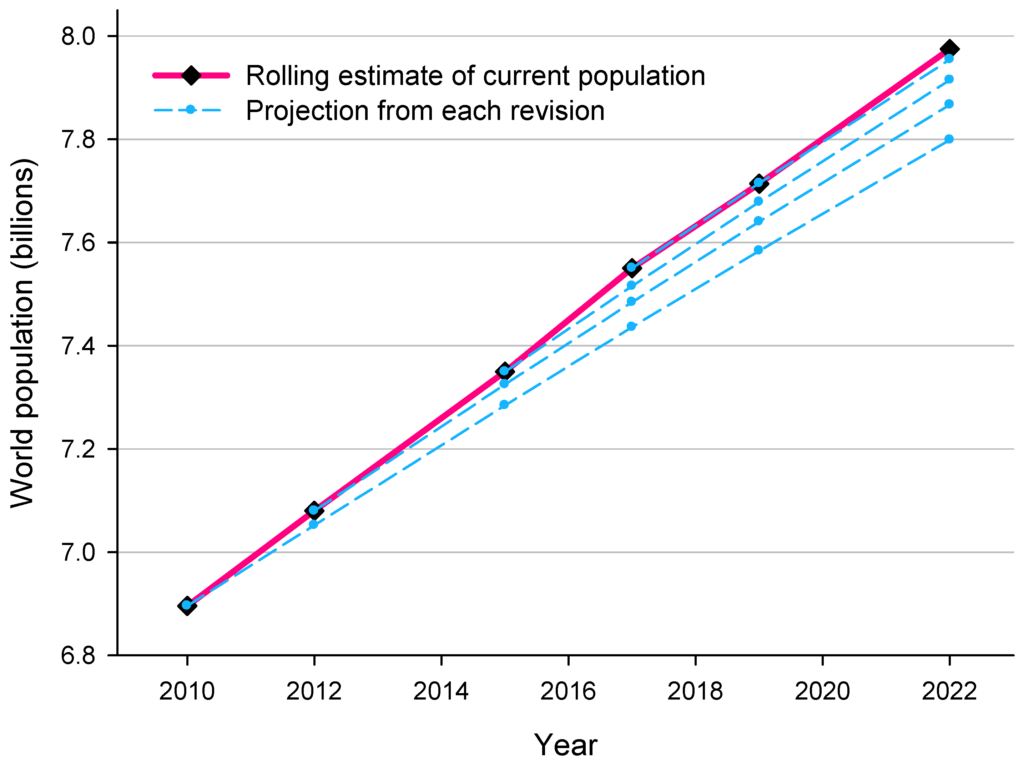

You wrote about the difference between the UN Population Division’s 2000 population projection for 2022 and its 2022 population estimate in 2022. Relatively speaking, is an “excess population” of 253 million over 22 years so far off the original projection?

It’s about two-thirds of the difference between the 2000 Revision’s medium and high projections1. They didn’t publish probabilistic projections then, but it would be well above the range within the 95% confidence interval. It’s only 15% more than the total growth anticipated over those 22 years, but the projections diverge over time, so it represents a difference of several billion by the end of the century. So, yes, it is a considerable failure.

The bigger problem is that their consistent error has not led to a revision of the model calibration and has not led to any circumspection about how “successful” the post-Cairo2 policy settings have been.

Do you think the UN Population Division has an agenda it’s trying to support with its projections, or do you think demographers there truly believe that with each data revision we’re on the cusp of rapid fertility decline?

I think the UN demographers are doing their best to produce accurate projections. I think they would see it as beyond their remit to explore what changes different interventions might cause, but the consequence is that they present projections as if they are purely a matter of chance and there is nothing we can do about it. I think the probabilistic projections probably further suppressed ideas about how future population could be influenced: The focus on chance to some extent displaced the focus on choices.

I can see how the rapid fertility transitions experienced by some countries in the 1970s and ’80s influenced the expected transitions in the remaining high-fertility countries. But it concerns me that they are not adjusting the model to reflect the much slower transitions that have been the norm over the post-Cairo2 period.

Is it unreasonable to assume that high-fertility countries would experience rapid fertility decline if those countries and the donor community committed the amount of funding necessary to address all unmet need for family planning? In other words, if they experienced the “active family planning programs” that many countries in the 1970s to 1990s experienced? Or is lingering high fertility due to large family size preferences?

The family planning programs in the 1970s did more than address access to contraception—they actively sought to reduce people’s family size preferences. They engaged in a wide range of messaging, from posters and radio announcements to in-home advice from health workers. It is politically correct these days to regard all such efforts to influence reproductive choices as coercive, lumped together with forced sterilizations and abortions. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) has been guilty of gratuitously linking population concern with forced sterilizations. There is no other instance where giving people truthful advice about the impacts of their choices is regarded as unacceptable. Is it coercive to promote immunization programs, or to tell people that smoking can harm their health? There has always been a role for persuasion in public health campaigns, and persuasion is not coercion.

The reason small family promotion is necessary is that cultural norms are very sticky. It is true that most African women express a preference for large families, but within their culture, this is more about expectation and conformity than a considered choice. People need to be given license to question cultural norms, and moral support to resist them. Voluntary family planning programs have been very effective in shifting these norms. They might enlist religious leaders to endorse contraception, or radio dramas to show people how characters just like themselves explore the issues and are empowered to change. When relieved of cultural pressures to marry early and produce children, and when permitted to pursue education and economic opportunities, most women do choose small families. But just providing access to contraception will not get them there.

Some commentary suggests that Africa is unique in its resistance to fertility decline, but I am unconvinced that African countries wouldn’t respond to proactive family planning efforts as well as other regions. There is certainly nothing to lose by trying. There are examples in Africa of rapid fertility changes, at the national or project level, in response to family planning interventions, but these efforts have not had the scale or duration to bring fertility down very far. Funding should not be a barrier—several studies have shown that family planning efforts save more money than they cost in unneeded health services for mothers and infants. It is a matter of political will.

Like you, we have been frustrated by UNFPA’s dismissal of population concerns and its celebration of the world reaching the 8 billion milestone, especially since supporting UNFPA is one of our legislative priorities. Do you know how much the UN agencies “talk” to each other? It seems odd that just about every UN agency besides the one founded to address population challenges regularly discusses how population growth drives or exacerbates various health, development, and environmental challenges.

I really don’t have much knowledge of the inner workings of the UN, beyond the accounts others have written. I know the Vatican has invested a lot of effort into countering the idea that population growth is bad for development, because this inconvenient fact places their ban on contraception in moral conflict. UNFPA is an obvious focus for them. The international women’s health movement was very influential at ICPD in 1994, and has maintained its influence with the implementation of the Cairo Programme of Action within the UN and family planning agencies. The origin of its bizarre conviction that all efforts to reduce birth rates were anti-women is a mystery to me, but smells like a well-seeded mythology. Institutional culture can be shifted over time by subtle influences over acceptable language and staff appointments.

Are there other explanations for the values shift that occurred at ICPD, which led to today’s “population complacency,” besides China’s one-child policy and India’s sterilization campaigns of the 1970s? It doesn’t make sense that warranted condemnation of these two coercive programs would be enough to dismiss an entire field of study and reject an entire suite of policy options when voluntary, rights-based programs were having such positive outcomes elsewhere.

The only way it makes sense to me is as a deliberate campaign of misinformation. I’m not suggesting that everyone involved is insincere, but the whole discourse has been carefully groomed to undermine the support that was once so widespread for population stabilization. The incidents of human rights abuses in China and India have been used to tar the whole family planning movement with the same brush.

A number of groups with different agendas have contributed to it. Anti-Malthusianism3 has always been a strong tenet for some leftists influenced by Karl Marx and Henry George4, but it equally suits global corporate elites who want ever more production and consumption to grow their enterprises, and ever more cheap labor to keep profit margins high. The leftists don’t seem to have cottoned on to their strange bedfellows, and how they themselves contribute to inequality and corporate globalization by stifling discussion of population growth and its negative impacts.

Developing country governments were initially skeptical also. There is always a tendency for political leaders to feel that their power is proportional to their country’s population. When the UN started to engage with population stabilization back in the 1960s and early ’70s, there was resistance from countries that suspected it was a Western agenda to prevent other races overpowering them. But this skepticism seemed to dissipate in the 1970s as countries started to realize that they really couldn’t make economic headway against such high rates of population growth, and as the successes of voluntary family planning were becoming evident especially in East- and Southeast Asia.

That’s when the misinformation started to emerge as a major influence. Through the Global Gag Rule, family planning was linked to abortion, despite contraception being the biggest preventer of abortions. UNFPA was accused of aiding and abetting China’s human rights abuses, when all the evidence showed it was a moderating influence. The economic revisionism, which claimed population growth could be a boon for development, was led by Julian Simon5, who evidently received backing and promotion from the Catholic Church. And myths that family planning programs had had no influence on fertility, that population concern was “politically motivated” and proven wrong by the Green Revolution6, and that its proponents were linked to racism and eugenics7, all coalesced into a rewriting of history.

In your research, have you encountered others who believe that ICPD had the inadvertent effect of diminishing the urgency around family planning programs and enthusiasm for financially supporting them? Has anyone in a position to affect funding levels been receptive to this consideration?

It’s an unfortunate fact that “women’s reproductive health” does not attract the same level of political commitment as “rapid population growth will scupper economic development.” There are plenty of people who commented at the time of ICPD that reducing the focus on population growth would reduce political commitment and funding for the services delivering women’s reproductive health and rights. Stanley Johnson anticipated this in his 1995 book The Politics of Population: Cairo 1994. Steven Sinding8 documented the decline in funding, as did the impressive inquiry report by the UK All-Parliamentary Committee on Population and Development in 2009. These voices contributed to motivating the 2012 London Family Planning Summit, which was a very welcome and somewhat successful attempt to renew the funding. However, its implementation body, Family Planning 2020 (FP2020), only achieved half its goal by 2020, which, given population growth in the meantime, was not enough to diminish the number of women with unmet needs at all. FP2030 is continuing the cause, but without recognizing the pivotal importance of fertility decline for development and security, it is just one of many pressing agendas in health portfolios. As Malcolm Potts9 has commented, “The ultimate tragedy is that the idealism at Cairo2 has actually left women worse off.”

One sentence in your paper really surprised me: “Little if any effect of education has been observed on desired family size.” Why do you suppose so much emphasis has been placed on female education as a way to reduce fertility if the evidence doesn’t show that it works (in the absence of strong family planning programs)?

The relationship between education and fertility is complex. There seems to be wide consensus that more educated women are better able to avoid unwanted pregnancies, so they have fewer unwanted and mistimed children. There might also be an effect of the job opportunities available to more educated women causing them to delay childbearing. But education per se doesn’t seem to change their desired family size, unless it includes learning about the benefits of smaller families and dispels negative misconceptions about modern contraception. The main point is that the difference between countries where fertility has declined rapidly and those where fertility declined slowly can’t be attributed to levels of education or efforts to improve education for girls. Those differences are overwhelmingly attributable to family planning program efforts.

I think the emphasis on girls’ education has been encouraged as a dismissal of the need for family planning promotion. It is part of building the myth that voluntary family planning programs didn’t work. That feeds into the myth that all the people who promoted such programs in the past had other, racist, or misanthropic motives—in UNFPA’s words, that they “prioritized population control without heed to people’s reproductive aspirations, their health, or the health of their children”—and that they achieved nothing apart from human rights abuses. To quote UNFPA again, “[E]ngineering population numbers has not proven successful in the past. Rather, it only serves to undermine human rights, including reproductive rights…” These are gross misrepresentations, for which UNFPA has not been called to account because it controls the discourse. By holding this line, it has actually become a barrier to effective assistance for poor countries.

Of course, most of the people who believe, and repeat, that girls’ education is the key to population stabilization, don’t understand that they are harming people in high-fertility countries by undermining effective approaches to fertility reduction.

What does influence women’s desired family sizes? The presence of strong family planning programs alone?

Culture is the biggest influence on desired family size. There doesn’t seem to be an innate instinct driving women or men to have many children, but they are strongly influenced by cultural norms. With the fall in infant mortality, those norms became maladaptive. Family planning promotion has been vital for overcoming cultural resistance and allowing people to embrace fertility choices as an empowering freedom.

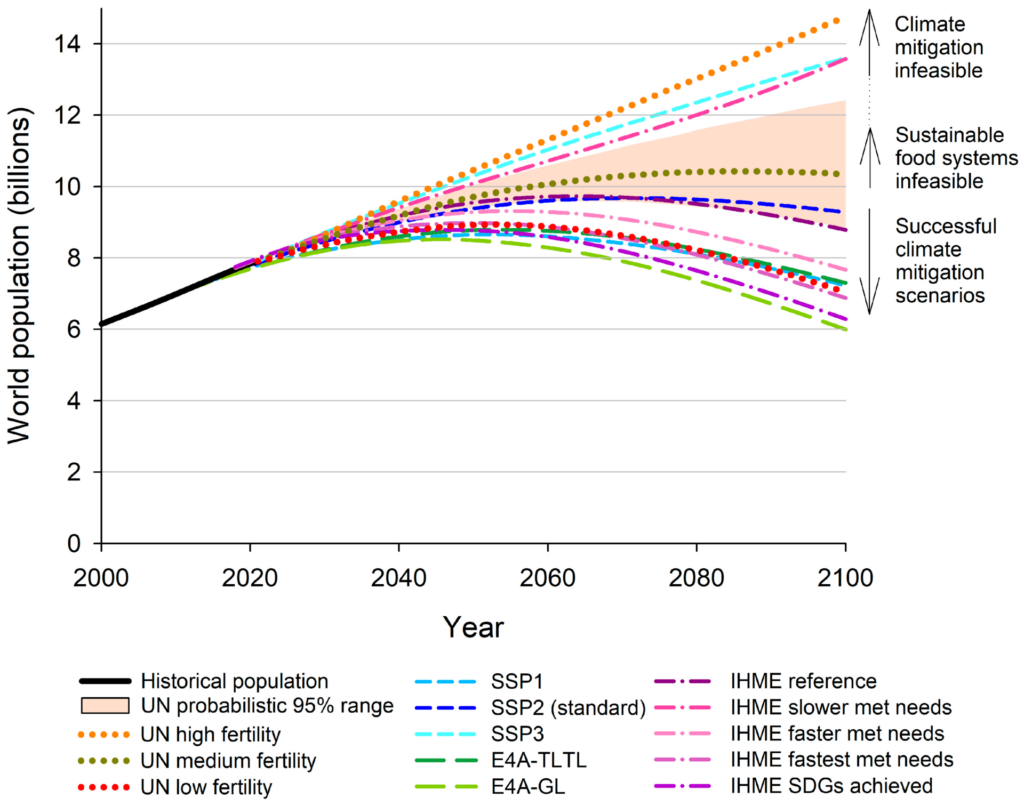

We were perplexed, as you were, by the Earth4All10 projections, especially the researchers’ declaration that the planet could support billions more people if we all lived just above the poverty line. Why would that be anyone’s vision for the future?

There are a lot of people motivated to play down the role of population growth in our global predicament, because they think it is a deliberate plot to blame the poor for the excesses of the rich. I suspect the Earth4All team is of this ilk. Their statements about population being unimportant and Earth being able to support billions more people don’t tally with their own results that show planetary boundaries for environmental impacts being exceeded even under their most optimistic scenarios.

Is there a similar Reproductive Justice movement in Australia to the one we have in the United States? If so, does it also denounce population concerns? (We are in complete support of the RJ agenda and work in coalition with many RJ groups. The one qualm we have with the movement is its patent dismissal of, and even hostility toward, any discussion around population challenges.)

Australia does not have the same controversy over abortion as in the U.S. In the last few years, there has been a flurry of state law reforms to decriminalize abortion and make it more accessible. Members of Sustainable Population Australia campaigned alongside reproductive rights organizations like Children by Choice to get these laws passed, and we were welcomed in those campaigns. We do face hostility from many people in environment and social justice movements who think population stabilization is all about racism, xenophobia, and eugenics. For many of them, justice must be about bringing down the oppressors, so anyone who suggests that poverty and deprivation can be endogenously generated by population growth is a blasphemous apologist for corporate elites and neocolonialism. I find it exasperating that they are unwittingly serving those corporate elites through this stance.

Can you explain why there is such strong support for the narrative that slower population growth will damage economies when there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that there are effective mitigating options and opportunities (working longer, automation and AI, eager would-be immigrants, etc.)?

Follow the money. Big business makes a lot of money from population growth, even as it impoverishes the general public. A stable or shrinking population would have many economic advantages, with a tighter labor market starting to narrow the gap between rich and poor, infrastructure improving rather than struggling to keep up with growth, and good housing becoming more affordable. But it doesn’t make big profits for capital. Demand for investment capital is lower, rents aren’t constantly inflating, and fewer people are in debt and paying interest to the banks.

To my mind, the focus on age structure and dependency ratios has been a huge red herring. It emerged as a side effect of the ‘demographic dividend’ theory, that high-fertility countries were not held back by population growth per se but by low proportions of “working age” people. The popularity of that theory seems to stem from its ability to at least partially explain the conspicuous economic success of every developing country that reduced fertility, in stark contrast to the stagnation in those that didn’t, without conceding that the “revisionists” were wrong and population growth impedes development after all. There is no real evidence that labor supply was or is an economic constraint in any high-fertility country. There is no evidence to date that labor supply is a constraint in any aging, low-fertility country. The constant cries of “labor shortages” have much more to do with profit margins getting tighter as energy prices climb, and cheaper labor being the obvious way out. But the countries that do have declining populations have seen greater workforce participation, lower unemployment, less income inequality, and greater productivity gains than similarly rich countries with rapid population growth due to immigration. As countries age, the pension bill is likely to be a bigger part of national spending, but that will be offset by lower costs for infrastructure, education, law and order, unemployment benefits, and environmental remediation.

Perhaps we need another decade to see how countries with shrinking populations perform. Hopefully that will dispel the fears and highlight the many advantages. However, it is difficult to feel confident that we have another decade of otherwise normal economic circumstances, given the rapid escalation of environmental disasters and geopolitical frictions. I hope we haven’t left our run too late.

Notes

- The UN Population Division’s medium population projection is the median of several thousand projections made using various fertility and mortality assumptions. The high projection assumes that the total fertility rate is 0.5 births higher than in the medium projection in each country throughout the projection period. For more details, see population.un.org/wpp/DefinitionOfProjectionScenarios.

- Cairo is shorthand for the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, Egypt, in 1994. This conference was a watershed moment in the population movement; it’s when the international agenda shifted from population stabilization via family planning programs to reproductive health, rights, and justice to the exclusion of population concerns. Although the Programme of Action that came out of the conference didn’t explicitly condemn population efforts, UNFPA’s subsequent interpretation of the conference’s mandate has ensured that population has been a third rail topic ever since.

- Thomas Robert Malthus wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population, published in 1798, about his concern that population growth would outstrip growth in agricultural yields, leading to famine and mass starvation.

- Henry George is the author of Progress and Poverty, published in 1879; he argued that people should only be taxed once, on the land they own.

- Julian Simon was a business professor who disputed the unsustainability of population growth and won a wager against Paul Ehrlich about whether the price of certain goods would rise or fall between 1980 and 1990.

- The Green Revolution saw the introduction of high-performing wheat, maize, and rice varieties in the 1960s and ’70s, together with fertilizers and other technologies, which dramatically increased food security in developing countries.

- Eugenics is the despicable, debunked theory that “desirable” human traits should be passed down through higher fertility of certain people and that less desirable traits should be stamped out by reducing/eliminating fertility of other people.

- Steven Sinding is a former Director-General of the International Planned Parenthood Federation who has had a decades-long career in population programming, funding, advising, and university education.

- Malcolm Potts is a human reproductive scientist and a professor of public health at the University of California, Berkeley.

- Earth4All is a collaborative initiative by the Club of Rome, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, the Stockholm Resilience Centre, and the Norwegian Business School.

Dr. Jane O’Sullivan is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, an Executive Member of Sustainable Population Australia, and a Co-convener of The Overpopulation Project. Trained as an agricultural scientist, she has led international research on tropical root crops in subsistence and semi-subsistence farming systems in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, before shifting her focus to the threats posed by population growth to food security, economic development, and ecological sustainability, and the effectiveness of measures available to limit population growth.