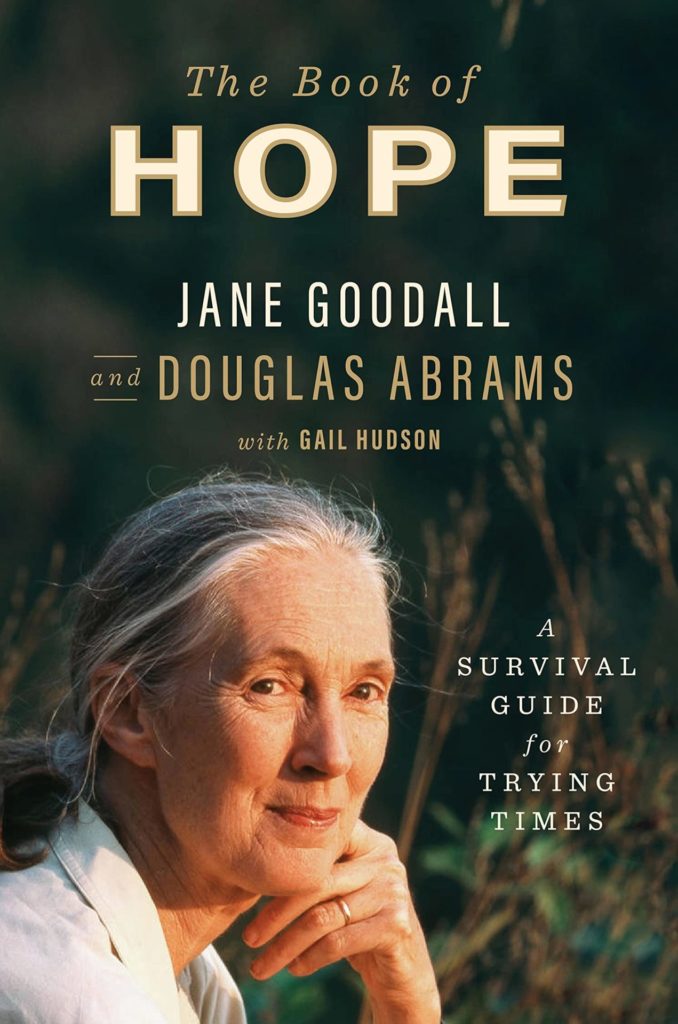

Excerpts From The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times

Written by Jane Goodall and Douglas Abrams | Published: December 13, 2021

Copyright (c) 2021 by the authors and reprinted with permission of Celadon Books, a division of Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC.

The Book of Hope is largely a transcript of several long-form interviews that author Douglas Abrams conducted with Jane Goodall over the course of several months—in Tanzania, in Belgium, and over Zoom, once the pandemic prevented them from continuing to meet up in person. I read it quickly, over a few hours on a Sunday evening, my mind’s eye picturing the stories Dr. Jane told of her breathtaking encounters with wild animals in East Africa. From the seminal experience of witnessing a male chimpanzee use a long piece of grass to fish termites out of a hole in the ground, which taught us that humans aren’t the only animal that uses tools, to the poisonous snake that slithered over her legs when she was first living in what later became Gombe Stream National Park, to the embrace from a female chimp as she was being released from rehabilitation, Dr. Jane’s stories inspire awe and reverence.

She is endlessly dedicated to mitigating the intergenerational injustice she [rightly] feels we are committing against today’s youth as we destroy nature and threaten the planet to the point of uninhabitability. And through her Roots & Shoots program, which asks kids to take on projects that make the world a better place for people, animals, and the environment, she empowers hundreds of thousands of young people across 68 countries to help reverse the damage their elders have inflicted on the earth. I think she’d really like our Population Education program, which is similarly dedicated to empowering young people to be better planetary stewards than the generations that came before them.

Please enjoy the following selected excerpts from her new book and purchase your copy in time to read it before our January Page Turners book club meeting! We’ll be discussing The Book of Hope as a group on Zoom on January 27, 2022. Details and the link to register are on our website at popconnect.org/virtual-events/book-club/. See you there!

–Marian Starkey

During my early days in Gombe I was in my own magical world, continually learning new things about the chimpanzees and the forest. But in 1986 everything changed. By then there were several other field sites across Africa and I helped to organize a conference to bring these scientists together.”

It was at this conference that Jane learned that in every place where chimps were being studied across their range their numbers were dropping and their forests were being destroyed. They were being hunted for bushmeat, caught in snares, and exposed to human diseases. Mothers were shot so their infants could be taken and sold as pets or to zoos, or trained for the circus, or used for medical research.

Jane told me how she secured funding to visit six different countries across the chimpanzee range in Africa. “I learned a great deal about the problems facing the chimps,” she said, “but I also learned about the problems facing human populations living in and around chimpanzee forests. The crippling poverty, lack of good education and health facilities, degradation of the land as their populations grew.

“More people were living there than the land could support, too poor to buy food from elsewhere, struggling to survive.”

“When I went to Gombe in 1960,” Jane said, “it was part of the great equatorial forest belt that stretched across Africa. By 1990, it had become a tiny oasis of forest surrounded by completely bare hills. More people were living there than the land could support, too poor to buy food from elsewhere, struggling to survive. Trees had been cleared to grow food or make charcoal.

“I realized that if we couldn’t help people find a way of making a living without destroying the environment, there was no way we could try to save the chimpanzees.”

(pp. 23-24)

“So, yes,” Jane continued, “I honestly think it was the explosion of the human intellect that took a rather weak and unexceptional species of prehistoric apes and turned them into the self-appointed masters of the world.”

“But if we’re so much more intelligent than other animals, how come we do so many stupid things?” I asked.

“Ah!” said Jane. “That’s why I say ‘intellectual’ rather than ‘intelligent.’ An intelligent animal would not destroy its only home—which is what we have been doing for a very long time. Of course, some people are indeed highly intelligent, but so many are not. We labeled ourselves Homo sapiens, the ‘wise man,’ but unfortunately there is not enough wisdom in the world today.”

(p. 46)

“So it is really strange, isn’t it, that this amazing human intellect has also gotten us into this mess we’re in,” I said. “This very same intellect has created a world out of balance. One could argue that the human intellect was the greatest mistake in evolution—a mistake that is now threatening all life on the planet.”

“Yes, we have certainly made a mess of things,” Jane agreed. “But it’s the way we have used the intellect that has made the mess, not the intellect per se. It’s a mixture of greed, hate, fear, and desire for power that has caused us to use our intellect in unfortunate ways. But the good news is that an intellect smart enough to create nuclear weapons and AI is also, surely, capable of coming up with ways to heal the harm we have inflicted on this poor old planet. And indeed, now that we’ve become more and more aware of what we’ve done, we have begun to use our creativity and inventiveness to start healing the harm we’ve caused. Already there are innovative solutions, including renewable energy, regenerative farming and permaculture, moving toward a plant-based diet, and many others, that are directed toward creating a new way of doing things. And, as individuals, we are recognizing that we need to leave a lighter ecological footprint and we are thinking of ways to do it.”

“So our intellect in itself is neither good nor bad—it depends on how we humans choose to use it—to make the world better or to destroy it?”

“Yes, that’s where our intellect and our use of words makes us different from other animals. We are both worse and better, because we have the ability to choose.” Jane smiled. “We’re half sinner and half saint.”

(pp. 47-48)

“I think that wisdom involves using our powerful intellect to recognize the consequences of our actions and to think of the well-being of the whole. Unfortunately, Doug, we have lost the long-term perspective, and we are suffering from an absurd and very unwise belief that there can be unlimited economic development on a planet of finite natural resources, focusing on short-term results or profits at the expense of long-term interests. And if we carry on like this—well, I don’t like to think what will happen. And it is most definitely not the behavior of a ‘wise ape.’

“When making decisions most people ask, ‘Will it help me or my family now or the next shareholders’ meeting or my next election campaign?’ The hallmark of wisdom is asking, ‘What effects will the decision I make today have on future generations? On the health of the planet?’

“There are over seven billion of us today, and already, in many places, we have used up nature’s finite natural resources faster than nature can replenish them.”

“And it’s the same sort of lack of wisdom shown by those in power who suppress certain sections of society—I mean, in America and the UK it is shameful the way certain sections of society are deliberately kept undereducated and underserved. And then the time comes when the resentment and anger of those people finally erupts, and they demand change. They want better wages or better health care or better schools. And this can lead to violence and bloodshed. Think of the French Revolution. And it was people fighting to end slavery that led to the American Civil War. Well, you and I both know of many stories of angry people coming together throughout history and using violence to overthrow oppressive political or social structures.”

(pp. 58-59)

How could we use this amazing human intellect wisely?

I put this question to Jane.

“Well, if we are ever going to do that—and I’ve already said that I think head and heart must work together—now is the time to prove that we can. Because if we don’t act wisely now to slow down the heating of the planet and the loss of plant and animal life, it may be too late. We need to come together and solve these existential threats to life on Earth. And to do so, we must solve four great challenges—I know these four by heart because I often speak about them in my talks.

“First—we must alleviate poverty. If you are living in crippling poverty, you will cut down the last tree to grow food. Or fish the last fish because you’re desperate to feed your family. In an urban area you will buy the cheapest food—you do not have the luxury of choosing a more ethically produced product.

“Second, we must reduce the unsustainable lifestyles of the affluent. Let’s face it, so many people have way more stuff than they need—or even want.

“Third, we must eliminate corruption, for without good governance and honest leadership, we cannot work together to solve our enormous social and environmental challenges.

“And finally, we must face up to the problems caused by growing populations of humans and their livestock. There are over seven billion of us today, and already, in many places, we have used up nature’s finite natural resources faster than nature can replenish them. And by 2050 there will apparently be closer to ten billion of us. If we carry on with business as usual, that spells the end of life on Earth as we know it.”

(pp. 59-60)

Of course, a great deal of our onslaught on Mother Nature is not really lack of intelligence but a lack of compassion for future generations and the health of the planet: sheer selfish greed for short-term benefits to increase the wealth and power of individuals, corporations, and governments. The rest is due to thoughtlessness, lack of education, and poverty. In other words, there seems to be a disconnect between our clever brain and our compassionate heart. True wisdom requires both thinking with our head and understanding with our heart.”

(p. 60)

A 2019 study published by the United Nations reports that species are going extinct tens to hundreds of times faster than would be natural and that a million species of animals and plants could become extinct in the next few decades as a result of human activity. We’ve already wiped out 60 percent of all mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles—scientists are calling it the “sixth great extinction.”

I shared these fears with Jane.

“It’s true,” she acknowledged. “There are indeed a lot of situations when nature seems to have been pushed to the breaking point by our destructive behavior.”

“Yet,” I said, “you still say you have hope in nature’s resilience. Honestly, the studies and projections about the future of our planet are so grim. Is it really possible for nature to survive this onslaught of human devastation?”

“So the big challenge faced by many species today is whether or not they can adapt to climate change and human encroachment into their habitats.”

“Actually, Doug, this is exactly why writing this book is so important. I meet so many people, including those who have worked to protect nature, who have lost all hope. They see places they have loved destroyed, projects they have worked on fail, efforts to save an area of wildlife overturned because governments and businesses put short-term gain, immediate profit, before protecting the environment for future generations. And because of all this there are more and more people of all ages who are feeling anxious and sometimes deeply depressed because of what they know is happening.”

“There’s a term for it,” I said. “Eco-grief.”

(pp. 72-73)

“The trouble is that not enough people are taking action,” I said. “You say more people are aware of the problems we face—so why aren’t more trying to do something about it?”

“It’s mostly because people are so overwhelmed by the magnitude of our folly that they feel helpless,” she replied. “They sink into apathy and despair, lose hope, and so do nothing. We must find ways to help people understand that each one of us has a role to play, no matter how small. Every day we make some impact on the planet. And the cumulative effect of millions of small ethical actions will truly make a difference. That’s the message I take around the world.”

“But sometimes don’t you feel that the problems are so huge that you are too overwhelmed to act, or else feel that anything you do is insignificant in the face of such enormous hurdles?”

“Oh, Doug, I’m not immune to all that’s going on and sometimes it hits me. When, for instance, I return to an area that I remember as a peaceful patch of woodland with trees and birds singing—and find that in just two years it’s been razed to the ground for yet another shopping mall. Of course I feel sad. But I feel angry, too, and try to pull myself together. I think of all the places that are still wild and beautiful and that the fight to save them must intensify. And I think of the places that have been saved by community action. Those are the stories that people need to hear; stories of the successful battles, the people who succeed because they won’t give up. The people who, if they lose one battle, gear up for the next.”

“Can these community actions win the overall battle, though?” I asked. “So many species are being lost. So many habitats destroyed—seemingly beyond repair. Is it not too late for us to prevent a total collapse of the natural world?”

Jane’s eyes looked into mine, and her gaze was level and direct.

“Doug, I honestly believe we can turn things around. But—yes, there is a ‘but’—we must get together and act now. We only have a small window of opportunity—a window that is closing all the time. So each of us must do what we can to start healing the harms we have inflicted and do our bit to slow down biodiversity loss and climate change. I have seen or heard about hundreds of successful campaigns and met so many wonderful people. And sharing these stories gives people hope—hope that we can do better.”

(pp. 78-79)

“It’s our extraordinary success in adapting to different environments that has allowed humanity—and cockroaches and rats!—to spread across the world. So the big challenge faced by many species today is whether or not they can adapt to climate change and human encroachment into their habitats.”

(p. 84)

“The chimps in Gombe make a nest and go to bed at night, which is what most chimpanzees do. But the chimps in Senegal, where the temperatures are soaring and getting ever hotter, have adapted. They often forage on moonlit nights because it’s much cooler. And they will even spend time in caves, which are very unchimp-like habitats.

“And chimps in Uganda have learned to forage at night for a different reason. Their forest is being increasingly encroached upon as villages expand and people need more land for farming.”

“And chimps in Uganda have learned to forage at night for a different reason. Their forest is being increasingly encroached upon as villages expand and people need more land for farming. And so, with their traditional foods becoming scarcer, the chimps have learned to raid farms adjacent to the forest and make off with farmers’ crops. That in itself is remarkable, as chimpanzees are typically very conservative in their habits and almost never experiment with new foods at Gombe. And if an infant tries to do so, the mother or elder sibling will hit it away! But the Ugandan chimps have not only developed a taste for foods such as sugarcane, bananas, mangoes, and papaya, but they’ve learned to make their raids in the moonlight—when they are less likely to encounter humans.

(pp. 85-86)

“With so many people on the planet—and the vast majority of animals being humans and our livestock, including our pets—we must set some areas aside for wildlife. And the thing is, this rewilding is really beginning to work!”

(p. 88)

“And it’s not just about benefiting animals. I try to make people understand how much we humans depend on the natural world for food, air, water, clothing—everything. But ecosystems must be healthy to provide for our needs. When I was in Gombe I learned, from my hours in the rain forest, how every species has a role to play, how everything is interconnected. Each time a species goes extinct it is as though a hole is torn in that wonderful tapestry of life. And as more holes appear, the ecosystem is weakened. In more and more places, the tapestry is so tattered that it is close to ecosystem collapse. And this is when it becomes important to try to put things right.”

(p. 96)

I asked Jane if she was ever asked if the money spent on conserving animals should be better used to help all the people in desperate need.

“You bet, I get asked that a lot,” Jane said.

“How do you reply?”

“Well, I point out that I personally believe that animals have as much right to inhabit this planet as we do. But also that we are animals as well, and JGI, like many other conservation organizations today, does care about people. In fact, it has become increasingly clear that conservation efforts will not be successful and sustainable unless the local communities benefit in some way and become involved. They must go hand in hand.”

“And you initiated this kind of program around Gombe,” I said. “Can you tell me how that work began?”

“With so many people on the planet—and the vast majority of animals being humans and our livestock, including our pets—we must set some areas aside for wildlife.”

“In 1987 I went to six countries in Africa where people were studying chimpanzees to find out more about why chimpanzee numbers were declining and what might be done about it. I learned a lot—about the destruction of forest habitats, the beginning of the bushmeat trade—that is, the commercial hunting of animals for food and the killing of mothers to sell their infants as pets or for entertainment. But during that same trip I began to realize also the plight faced by so many of the African people living in and around chimpanzee habitats. The terrible poverty, lack of health and education facilities, and degradation of the land.

“So I went on that trip to find out about chimp problems and realized they were inextricably linked to people problems. Unless we helped people, we could not help chimps. I began by learning more about the situation in the villages around Gombe.”

Jane told me that she thought most people found it hard to believe the level of poverty that existed then. There was no appropriate health care infrastructure, and no running water or electricity. Girls were expected to end their education after primary school to help in the house and on the farm and were married off as young as thirteen. Many older men had four wives and huge numbers of children.

“There was a primary school in each of the twelve villages around Gombe. The teachers had canes that were freely used, and much of the children’s time was spent in sweeping the bare earth of the schoolyard. Some villages had a clinic, but there were few medical supplies.

“And so, in 1994, JGI began Tacare. At the time it was a very new approach to conservation. George Strunden, who was the mastermind behind the program, selected a little team of seven local Tanzanians who went into the twelve villages and asked them what JGI could do to help. They wanted to grow more food and have better clinics and schools—so that’s where we started, working closely with Tanzanian government officials. We did not even talk about saving chimpanzees for the first few years.

“Because we started with local Tanzanians, the villagers came to trust us, and gradually we built a program that included tree planting and protecting water sources.”

“I heard you also set up microcredit banks?”

“Yes, I think this has been one of the really successful things we did. It was kind of magic that soon after Tacare began, Dr. Muhammad Yunus—who won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 and is one of my heroes—invited me to Bangladesh and introduced me to some of the women who had been among the first to receive tiny loans from his Grameen Bank. Dr. Yunus started this lending program because the big banks refused to give out small loans. The women told me it was the first time they had actually held money in their hands and the difference it had made. And that now they could afford to send their children to school. I was immediately determined to introduce this program to Tacare.

“On one of my subsequent visits to Gombe, the first recipients of the microloans that Tacare helped them obtain were invited to come and talk about the small businesses they had started. They were almost all women. One young woman—only about seventeen years old—was very shy but so eager to tell me how her life had changed. She had taken out a tiny loan and started a tree nursery, selling saplings for the village reforestation program. She was so proud. She had paid back her first loan; her business was making money; she was able to hire a young woman to help her; and she had actually been able to plan when she would have her second child, thanks to Tacare’s family planning information. And she told us she did not want more than three children because she wanted to be able to afford to educate them properly.”

“I know you see voluntarily curbing population growth,” I said, “and increasing access to education—especially for girls—as one of the keys to solving our environmental crisis.”

“Yes, absolutely essential. On a visit to another village,” Jane continued, “I gave a talk at the primary school and met one of the girls who had been awarded a Tacare scholarship that would enable her to move on to secondary education.

She was very shy but excited at the idea of going to a secondary school in town where she would be a boarder.”

Laughing, Jane told me how, at the start of this program, which was specifically designed to enable girls to stay in school during and after puberty, she had learned of a major problem. The girls were not going to school during their periods because the school latrines were stinky holes in the ground with no privacy whatsoever. Nor did they have any sanitary towels.

“So we planned to introduce ‘ventilator improved pit latrines.’ In America I suppose you would say VIP bathrooms. In the UK we’d say VIP loos!” She laughed again. “So that year I was asking for the money to build one of these as my birthday present. I raised enough for five! When they were built, I went to one of the schools for an official opening. It was a splendid event—parents in their smartest clothes, a few government officials, and a lot of excited children.

“The building had a cement floor, five little cubicles with doors that latched for the girls and, separated from these by a wall, three for boys. They had not yet been used. With great ceremony I cut the ribbon—then was escorted into the girls’ area by the headmistress and a photographer. I went into a cubical and, to do the thing properly, sat on the seat. But I didn’t pull my trousers down,” she ended with a mischievous grin.

“So you see,” she added, “these girls are now empowered to elevate their lives out of poverty and now understand that without a thriving ecosystem their families cannot thrive.

“Almost all of these villages have a forest reserve that needs protecting—but by 1990 most of them had been severely degraded—for firewood, for charcoal, and clear-cutting for growing crops. As most of Tanzania’s remaining chimpanzees live in these reserves, the situation was not very promising. But now everything has changed. Our Tacare program is now in one hundred and four villages throughout the range of Tanzania’s two thousand or so wild chimpanzees.

“Last year I went to one of these villages and met Hassan, one of their two forest monitors who had learned how to use a smart phone. He was eager to take us into ‘his’ forest and show us how he used the phone to record where he had found an illegally cut tree and an animal trap. He pointed out where new trees were now growing. He told us that he was seeing more and more animals—three days before he had seen a pangolin on his way home in the evening. And most exciting of all, he had seen traces of chimpanzees—three sleeping nests and some feces.”

(pp. 97-102)

Jane told me that the Tacare method is now operating in the six other African countries where JGI is working; and as a result, the chimpanzees and their forests, along with the other wildlife, are being protected by the people who live there, in whose hands their future lies.

“I see what you’re saying about the link between nature’s resilience and human resilience,” I said. “How addressing human injustices like poverty and gender oppression makes us better able to create hope for people and the environment. Our efforts to protect endangered species preserve biodiversity on the Earth—and when we protect all life, we inherently protect our own.”

(pp. 103-104)

“The tragedy is that a pandemic such as this one has long been predicted by those studying zoonotic diseases. Approximately 75 percent of all new human diseases come from our interactions with animals. COVID-19 is likely one of them. They start when a pathogen, such as a bacteria or virus, spills over from an animal to a human and bonds with a cell in a human. And this may lead to a new disease. Unfortunately for us, COVID-19 is highly contagious and it spread rapidly, soon affecting almost every country around the globe.

“If only we had listened to the scientists studying zoonotic diseases who have long warned that such a pandemic was inevitable if we continued to disrespect nature and disrespect animals. But their warnings fell on deaf ears. We didn’t listen and now we are paying a terrible price.

“By destroying habitats we force animals into closer contact with people, thus creating situations for pathogens to form new human diseases. And as the human population grows, people and their livestock are penetrating ever deeper into remaining wilderness areas, wanting more space to expand their villages and to farm. And animals are hunted, killed, and eaten. They or their body parts are trafficked—along with their pathogens—around the world. They are sold in wildlife markets for food, clothing, medicine, or for the trade in exotic pets. Conditions in almost all of these markets are not only horribly cruel but usually extremely unhygienic—blood, urine, and feces from stressed animals all over the place. Perfect opportunity for a virus to hop onto a human—and it is thought that this pandemic, like SARS, was created in a Chinese wildlife market. HIV-1 and HIV-2 originated from chimpanzees sold for bushmeat in wildlife markets in Central Africa. Ebola possibly started from eating gorilla meat.

“And as the human population grows, people and their livestock are penetrating ever deeper into remaining wilderness areas, wanting more space to expand their villages and to farm.”

“The horrific conditions in which billions of domestic animals are bred for food, milk, and eggs have also led to the spawning of new diseases such as the contagious swine flu that started on a factory farm in Mexico and noninfectious ones like E. coli, MRSA (staph), and salmonella. And don’t forget that all the animals I’ve been talking about are individuals with personalities. Many—and especially pigs—are highly intelligent, and each one knows fear, misery, and feels pain.”

(pp. 226-227)

“…I have something very important I want to convey: we must not let this distract us from the far greater threat to our future—the climate crisis and the loss of biodiversity—for if we cannot solve these threats, then it will be the end of life on Earth as we know it, including our own. We cannot live on if the natural world dies.”

(pp. 231-232)

“Together we CAN! Together we WILL!

“Yes, we can, and we will—for we must. Let us use the gift of our lives to make this a better world. For the sake of our children and theirs. For the sake of those struggling in poverty. For the sake of the lonely. And for the sake of our brothers and sisters in the natural world—the animals, the plants, the trees.”

(p. 234)