Fewer Births Can Lead to a Greater Society

Written by John Seager | Published: September 13, 2021

Elon Musk took a moment away from his astronautical machinations to deliver a finger-wagging Twitter warning for humanity: “Population collapse is potentially the greatest risk to the future of civilization.” Just how the annual global population increase of some 80 million people on our planet translates into a collapse seems like murky Musk math. The father of seven also thought we should know that “Mars has a great need for people, seeing as population is currently zero.” Zero population on Mars will come as news to, well, no one. It’s been zero humans since the dawn of time.

So far, 2021 has seen a riotous insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, extreme weather, water shortages, and the continued profound threat posed by Covid. Yet Musk is but one of many voices sounding false alarms about a spurious people shortage around the world and in the United States.

The Week breathlessly proclaimed the “doom-loop of a falling fertility rate.” CNBC posted this alarming headline: “Researchers expect the U.S. to face underpopulation, blaming a falling birth rate and economic crises,” while strangely failing to cite any such research. And the Wall Street Journal ran a story entitled, “U.S. Population Growth, an Economic Driver, Grinds to a Halt.”

Coverage was triggered by a 4 percent reduction in the U.S. birth rate from one year ago. Given the hysteria, you’d think it was a 40 percent decline. And just how much did the U.S. population plummet in 2020? Well, it didn’t. Rather, it rose by nearly one million, notwithstanding all the excess deaths related to Covid.

Leaving aside fuzzy arithmetic, what’s the fuss about? In a crisis-ridden world, do we need to push the panic button because women in the U.S. and many other places are choosing to have smaller families and to have them later in life?

In fact, these shifts can help solve some of our most intractable problems. They may avert some of the worst climate catastrophes. They can create opportunities for those who are often left out of our economy. And they might even help bring some measure of peace and quiet into a world that somehow feels like it’s spinning faster by the day.

Smaller Families, Older Americans

All across America, millions of women and couples are moving toward smaller families. Even Utah—home to many members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (better known as Mormons), long associated with large families—is now below replacement rate in terms of childbearing.

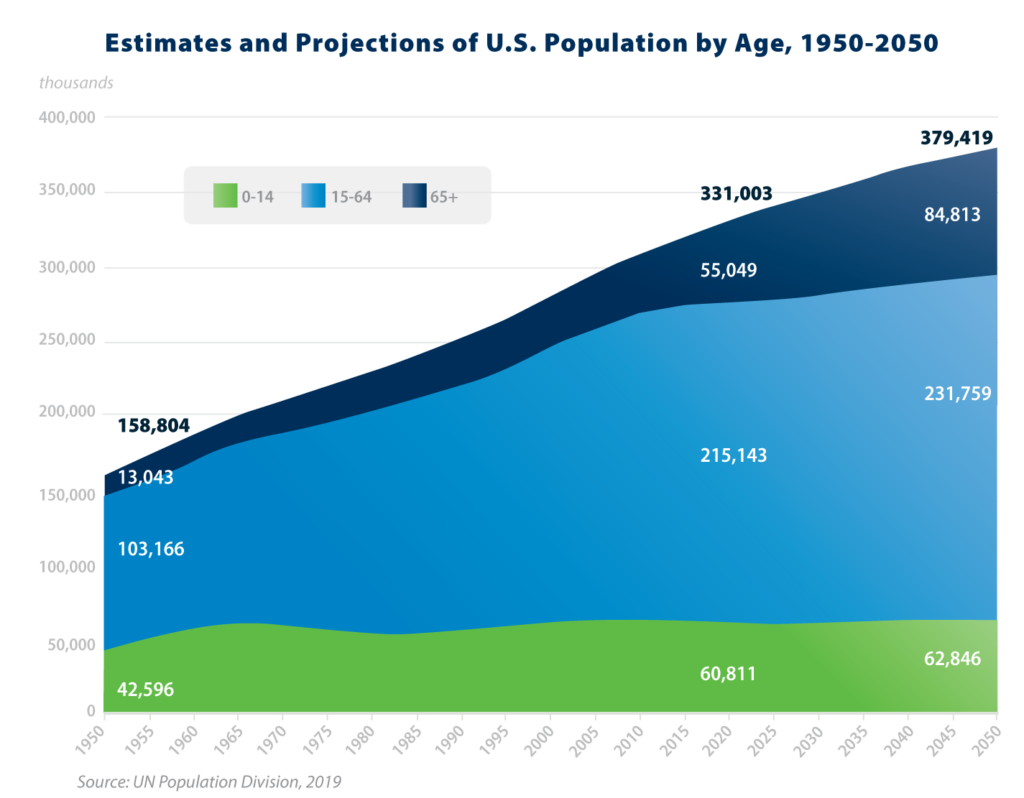

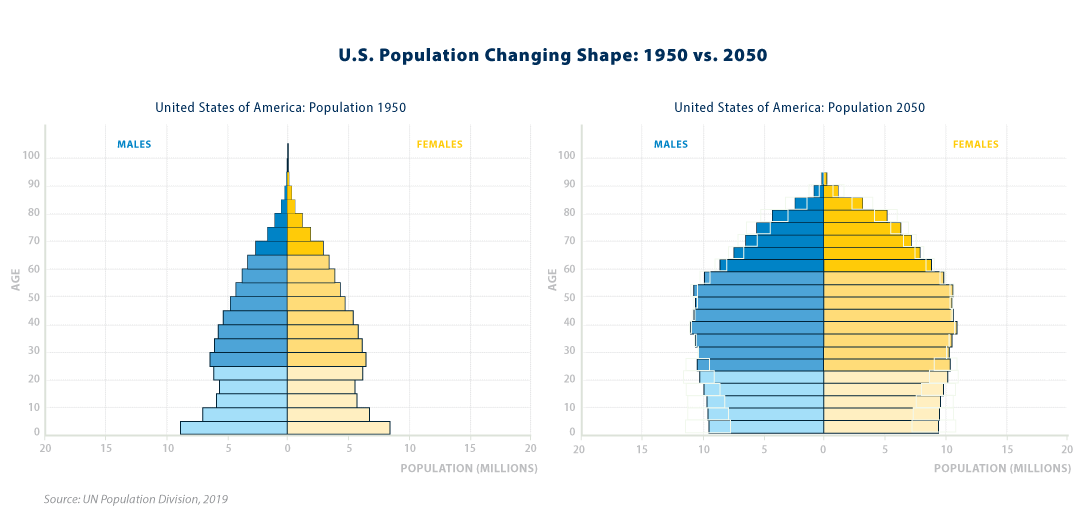

Demographic changes now underway can represent an extraordinary opportunity for us to focus on creating a greater society—as opposed to a larger one. In the midst of an unprecedented climate crisis and continued socioeconomic inequities, the age profile of Americans is undergoing a significant, albeit gradual, shift as birth rates decline. Certainly, we’ll need more nursing homes, but we’ll also need fewer nursery schools. More senior transportation services, but fewer school buses. More gerontologists, but fewer obstetricians. Yes, the ratio of workers to retirees will shrink, but the ratio of workers to young dependents will rise.

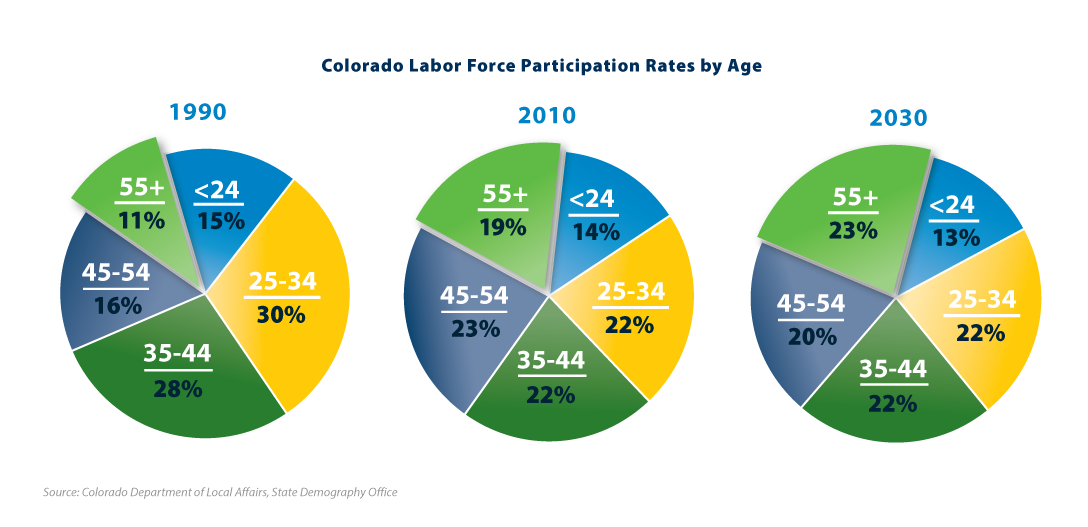

It’s fair to assert that age 65 doesn’t mean the same thing in a digital world as it did in prior eras when most jobs involved manual labor, which can exact a physical toll over time. And researchers have found that “connecting with other people through social activities and community programs can keep your brain active and help you feel less isolated and more engaged with the world around you.” One way to accomplish this is by remaining in the workforce. The U.S. labor force participation rate stood at 59.7 percent in June 1960. As of June 2021, it was 61.6 percent. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget office projects that it will be around 60.1 percent in 2050. In other words, no major changes. And no need for panic.

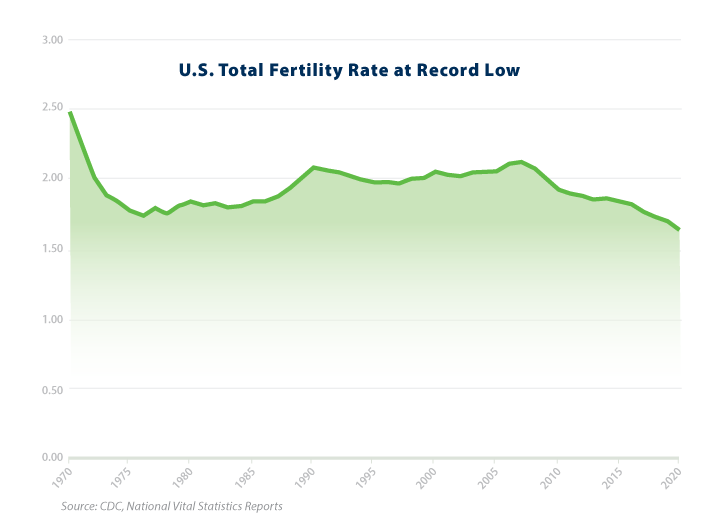

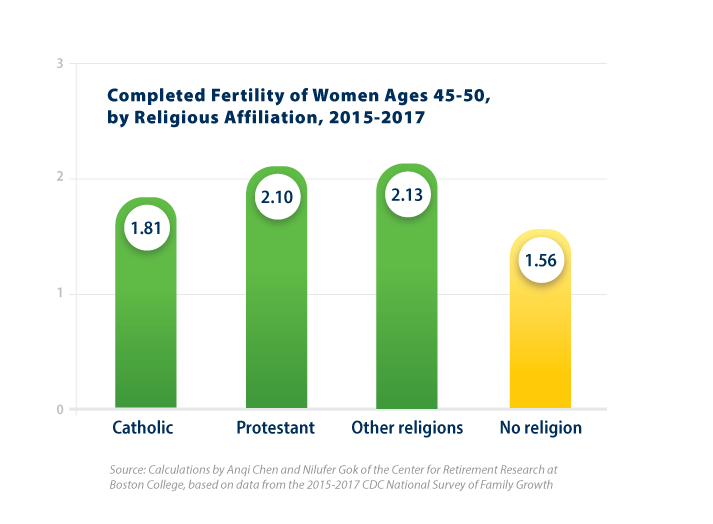

On a personal level, most Americans clearly understand that their own well-being and prosperity isn’t enhanced by having large families. Over the past several generations, the average American has stopped at two children or thereabouts. The total U.S. fertility rate in 2020 when Americans elected Joseph R. Biden, Jr., our second Roman Catholic President, was 1.78 children per women, as compared with 3.58 children per woman when we elected our first Catholic President, John F. Kennedy, in 1960. It may come as a surprise to many that U.S. Catholics have considerably smaller families than their Protestant counterparts. Those who practice no religion have even fewer children.

The fate of our nation—and our world—need not be tied to population growth. In fact, the opposite is true. A peer-reviewed scientific study concluded that we could achieve between 37 percent and 41 percent of needed reductions in greenhouse gas emissions by moving to a lower global population trajectory. The conspicuous silence of most environmental groups on this topic seems bewildering given the climate crisis.

While change can be disruptive, economic transformation is a fact of modern life. For example, none of today’s five largest U.S. companies even existed when the U.S. population hit 200 million in 1967. Remember when Amazon was just a river in South America? One need not view either the rise of the “new” Amazon or the destruction of rainforests in the original Amazon with equanimity to realize we must develop new strategies as our world changes. Finding ways to live well with a stable or declining population could ease the crushing pressures we’re now placing on our living planet.

Escaping the Poverty Trap

A stable U.S. population with fewer people entering the workforce could provide job opportunities for those members of the next generation who are currently trapped in poverty. When they grow up, they deserve the chance to find great jobs, which will benefit all of us.

While some have raised reasonable concerns that the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief legislation signed by President Biden, which includes a dramatic increase in child tax credits, may possibly result in some larger families, there are considerable benefits to ensuring that children grow up in stable environments. When it comes to population growth, stressed-out people simply don’t make great decisions about anything—including matters of reproduction. This landmark venture can help meet population challenges while improving children’s lives at the same time. Lifting the next generation out of poverty is key to population stabilization.

There are vital factors that can lead people everywhere to choose smaller families. We can act to make those outcomes more likely. There is strong evidence that Americans with higher incomes tend to use family planning more effectively. The Guttmacher Institute reports: “The rate of unintended pregnancy among women with incomes less than 100 percent of the [federal poverty level] was 112 per 1,000 in 2011, more than five times the rate among women with incomes of at least 200 percent of [the federal poverty level] (20 per 1,000 women).”

With 3.6 million U.S. births in 2020, and given that more than a third of U.S. births are unintended (37 percent, according to a 2012 CDC survey of new mothers), we can estimate that there were over 1.3 million unintended births in 2020. This outweighs our net immigration of 595,000 (in 2019—2020 data is not yet available) by more than a two-to-one ratio. If you’re looking for the leading source of U.S. population growth, it’s important to look first at unintended births.

Expansion of child tax credits could prove a great benefit for society by dramatically reducing the poverty rate. It could also help reduce population pressures. When you live in a state of constant worry about eviction, when your cupboards are bare, when you can’t pay the bills, and when you barely make enough money to get by even with two jobs, it’s hard to make positive decisions about anything—including family size.

Consider the nearly 12 million U.S. children who are trapped in poverty. Often, they suffer from poor health due to lack of adequate nutrition and medical care. Even before they begin school, they lag behind other students. Their parents are often so stressed out from working long hours that they can’t give their children needed care and attention. This is a prescription for social inequity at every level.

Even leaving aside the deep personal toll here, this represents an extraordinary waste of potential for a society that needs sophisticated, productive workers to compete in the Information Age. Children trapped in poverty tend to drop out of school and thus not advance their career opportunities.

More education strongly correlates with later childbearing—a Pew Research Center analysis of 2012 census data found that the average age at first birth for mothers ages 40-50 without a high school diploma was 24, while it was 30 for those with a Master’s degree. And later childbearing reduces a country’s total fertility rate. Consider “Emily,” who gives birth when she is 17, and “Jessica,” who doesn’t do so until she is 34. Jessica has essentially skipped an entire generation, which has a major impact in terms of reducing population growth.

The legislation signed by President Biden slashed the poverty rate for children in the United States by nearly 50 percent—at least temporarily, since the current measure expires at the end of the year. This reduction in poverty will mean healthier children. It will mean they’ll advance further in school. And down the road, it means they will, on average, postpone starting families.

The phrase “population stabilization” doesn’t appear in this landmark law, but no matter. Results are what count. We can shift from a vicious cycle of poverty and rapid population growth to a virtuous cycle of healthy, well-educated citizens who can make thoughtful decisions. Population stabilization won’t solve every problem, but it’s essential to achieving a sustainable future for all.

The Change We Need

As for worries about Social Security running out of money, if the cap on earnings subject to the Social Security tax were eliminated, the Congressional Research Service reports that Social Security would be in good shape through 2085. Lifting this cap would only affect about 5.9 percent of current American workers. Adjustments to Social Security have been made in the past and will no doubt be needed from time to time in the future. A system that taxes every worker at the same current rate would put the system on solid footing.

As family size shrinks, higher employment among working-aged women, who are still the primary caregivers, can help offset the shrinking ratio of workers to retirees. Also, smaller families make it easier to invest more per child in terms of health and education, which is a boon to our future economic productivity. Tomorrow’s jobs will mostly demand a highly skilled workforce. If less-skilled labor is needed, a healthy society can afford to pay living wages for that sort of hard work. The work will get done if the price is right.

Some fear that we’re entering an age of diminished innovation partly as a result of slower population growth. Economist Lyman Stone argues that “slower population growth reduces innovation, entrepreneurship, and economic dynamism, making everyone worse off.” U.S. population growth slowed over the past decade—those, like Stone, who view this as lessening the flow of new ideas, might want to check out the newest iPhone, which performs 11 trillion operations per second. It seems a bit illogical to write an obituary for innovation.

Past the Boiling Point

In reality, slower population growth should be seen as a breath of fresh air. And speaking of fresh air, while our air and water are cleaner than they were 50 years ago, most Americans are still understandably worried about air and water pollution. And we are among the primary drivers of global climate change.

While we typically think of climate change affecting faraway places, there are serious challenges facing us here at home as well. Out West, the Colorado River is in peril. California—which produces most of our fruits, vegetables, and nuts—relies on that river for crop irrigation. Lake Mead and Lake Powell, which are key parts of a water system relied on by 40 million people, are at historic lows. Hydroelectric production at Hoover Dam has plummeted by 25 percent. Slower population growth would reduce demands on the shrinking supply of fresh water in the American West. Back East, coastal communities such as Miami already face “sunny day” flooding due to climate-related sea level rise. Overbuilding, triggered by rapid population growth, in increasingly flood-prone areas is a prescription for disaster.

Fewer Can Be Better

Economies are man-made. While we can modify them to reflect changing needs, societies cannot hope to thrive when natural capital is depleted. Preserving our planet is the real bottom line. Population stabilization and eventual decline can play a key role.

Manageable shifts can unfold over decades and generations—though sooner would be much better. Demographers still project that U.S. population may rise by more than 100 million by 2100, although there are now some welcome estimates that our population growth may slow. The Congressional Budget Office recently revised its figure for U.S. population in 2050 downward by 11 million people. That’s roughly equal to the number of people now living in our 11 least populous states.

Going forward, we’ll have more older people and fewer younger people. We’ll have more women entering and staying in the paid labor force. And we’ll have more jobs carried out through automation. We can also have more green spaces and wildlife habitats, more investment in each American, and more hope for a planet that can comfortably support future generations. In terms of a sustainable future, less can be more.

Colorado Can Lead the Way

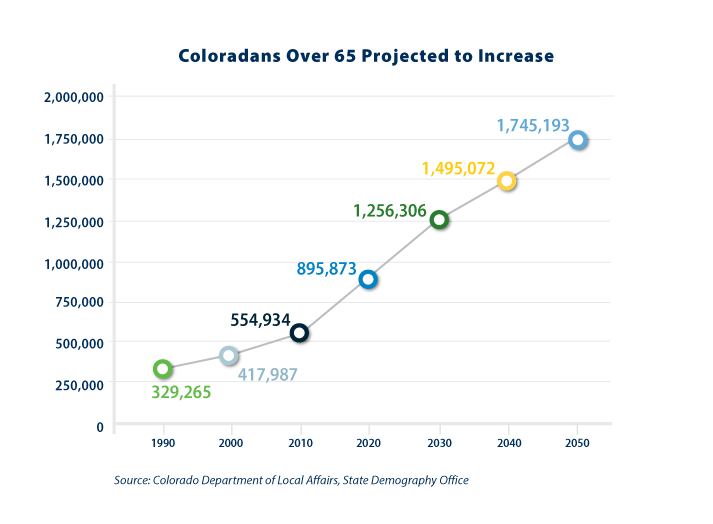

Older workers can be highly dependable, productive employees. Colorado, which has the second fastest growing number of people over 65, is taking the lead in identifying and removing barriers that prevent older Coloradans from participating in the workforce. According to the Bell Policy Center, older workers comprise the fastest growing segment of those who are employed in the state.

Four major impediments for older workers have been identified:

- Age discrimination and negative perceptions of older workers

- Inflexible workplaces

- Inadequate training and skill development opportunities

- Lack of comprehensive, disaggregated information

Overcoming these barriers requires political leadership. By making the issue a high priority, governors such as Colorado’s Jared Polis can open doors for older workers.

“We know the current and future generations of older Coloradans will provide economic, social, and civic value to our communities for decades to come. We have an opportunity to harness this value.”

“Unlike states that focused more on long-term care and health care and other traditional aging topics, here we had a focus on workforce,” says Janine Vanderburg, head of Changing the Narrative, a campaign to alter the way people think, talk, and act about aging and ageism. “I am optimistic that despite post-pandemic worries, Colorado will be in the forefront of older workers.”

Under the leadership of then-Governor, now U.S. Senator John Hickenlooper, Colorado became one of the first three states to join the AARP Network of Age-Friendly States and Communities. Colorado’s Boomer Bond program supports programs that enable aging residents to remain in their own homes. Employment options are just one key part of the social infrastructure needed to address a changing age profile.

How to Shrink Smart

Paradoxically, some places, especially in the middle of our country, are emptying out despite U.S. population growth. Most cities in Iowa have lost population. It can be devastating when a community loses vital services like schools and stores and its only hospital. If we’re going to find new pathways that don’t depend on population growth, we need to help some of these places find ways to thrive so we can demonstrate that population decline can be fully compatible with a high quality of life.

That’s the mission of researchers at Iowa State University (ISU) who are seeking to understand why some communities that are losing population are faring well while others are not. As part of the Shrink-Smart initiative, David Peters, Associate Professor of Sociology at ISU, notes, “Instead of seeing population loss as a problem, we need to start looking at it as a process that needs to be managed.” Peters also commented that “people tend to think of rural America as declining. They equate decreases in population with overall decline in quality of life. We wanted to ask if that’s really true, and we found that it doesn’t have to be.”

According to a Shrink-Smart analysis:

- Residents of smart shrinking towns are more civically engaged and have stronger social networks.

- These residents tend to say their towns are more trusting, supportive, and tolerant.

- Smart shrinking towns have more private and public investment.

- Residents say their leaders work on behalf of everyone and newcomers are welcomed as leaders, showing strong “bridging social capital,” a term that refers to how people connect across society.

One positive example is the small city of Bancroft, Iowa. While Bancroft has lost about one-third of its population since 1980, it has strong citizen engagement, a healthy town center, and a public-owned local utility that provides revenue to the community. A key local employer, Aluma, provides nearly 200 local jobs as it builds and ships some 300 aluminum trailers each week. According to Zillow, a typical home in Bancroft costs about $100,000. Small town life in rural Iowa isn’t for everyone, but it might prove attractive for some who feel priced out and left behind in overcrowded coastal communities.

The Good Crisis

Here in the U.S., we can enhance productivity without relying on population growth. In The Good Crisis: How Population Stabilization Can Foster a Healthy U.S. Economy, published by Population Connection, David Bloom, Harvard Professor of Economics and Demography, and Jay Lorsch, Harvard Professor of Human Relations, emphasized:

Here in the U.S., we can enhance productivity without relying on population growth. In The Good Crisis: How Population Stabilization Can Foster a Healthy U.S. Economy, published by Population Connection, David Bloom, Harvard Professor of Economics and Demography, and Jay Lorsch, Harvard Professor of Human Relations, emphasized:

It is clear that the fortunes of the U.S. are tied closely to the education, training, and health of its future workforce. Investing in school and health can offset the projected decline in the share of the working-age in the population. Such investments have the potential to magnify the size of the effective labor force insofar as more and better education and better health results in more productive adults. Investments can also be disproportionately directed toward minority populations to promote their employment, productivity, and earnings and stem the tide of further increases in income inequality.

Download a free electronic copy of The Good Crisis: How Population Stabilization Can Foster a Healthy U.S. Economy or order a hard copy from your favorite bookstore!