Nepal, Gagged

Written by Lisa J. Shannon | Published: March 2, 2020

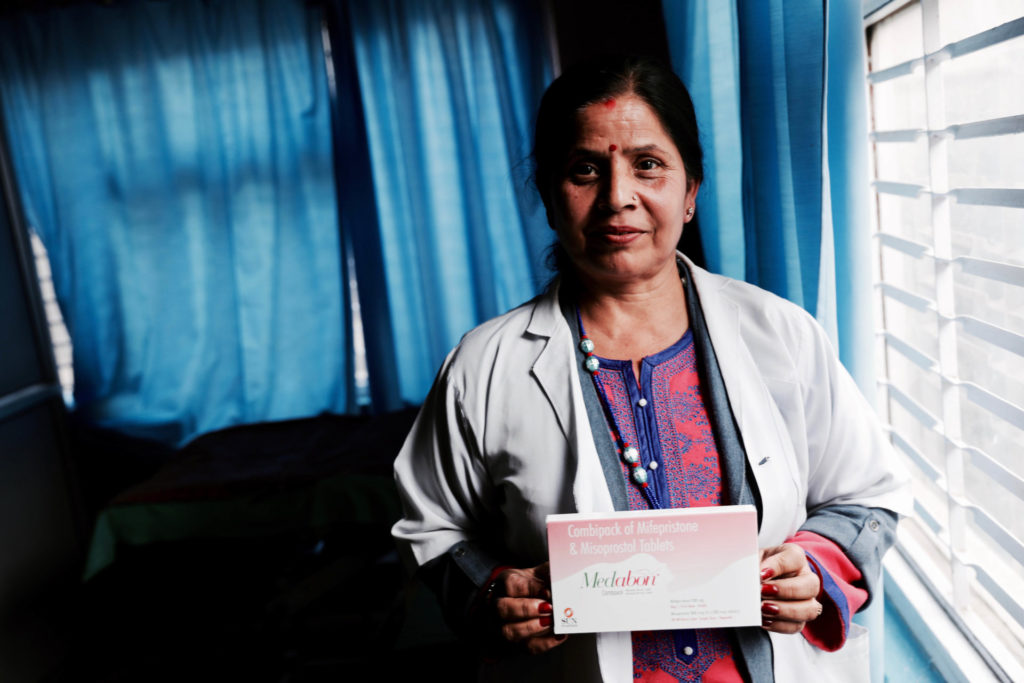

Today is my last day. Closing. Phase out,” Babita Bist says, with a bubbly Nepali accent. She’s wearing a loose ponytail and street clothes—no lab coat to indicate her nursing credentials. It’s late October 2018, and all things reproductive health in Nepal are changing. Due to the funding cuts that have come with Trump’s Global Gag Rule, Babita Bist has just completed her last day in the field, working in mobile clinics. Babita repeats herself, perhaps for clarity, perhaps to drive the point home: “Phase out.”

We are sitting in an office-turned-exam-room at the Kathmandu headquarters of Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), founded in 1959, before Nepal even had a Ministry of Health. Small stainless steel desks and office chairs are surrounded by shiny lime curtains, canary yellow walls, and an assortment of rubber gloves and medical supplies. Patients are ushered in and out of the exam room by Babita’s fellow nurse, 35-year-old Saraswati Upreti. Babita sits at a desk, contemplating the change. As of today, Babita will not be heading out to the field. She says, “Funding is finished. Mobile clinics are closed.”

Babita had worked training government health staff in remote locales, focusing on marginalized communities. It was an Obama-era USAID project designed to “target those groups and disadvantaged populations with the highest unmet need for family planning services,” first implemented in 2010 by Marie Stopes Nepal and FPAN. The second phase of the work constituted a $10 million investment over four years, beginning in 2015. It was scheduled for completion in mid-2019, but due to Trump’s Global Gag Rule, funding was withdrawn mid-project, and the effort to make five methods of contraception widely available in Nepal was curbed.

Nepal, Poster Child for Successful Policy Change

Babita and Saraswati were both coming of age when Nepal liberalized its abortion law in 2002, legalizing abortion up to 12 weeks gestation on request, 18 weeks in the case of rape or incest, and at any point if there was a fetal anomaly or serious health risk to the pregnant woman. In 2018, the law was liberalized even further: The Safe Motherhood and Reproductive Health Rights Act acknowledged access to abortion as a human right and extended abortion availability from 18 to 28 weeks gestation in cases of rape, incest, fetal anomaly, threat to a woman’s health or life, or when the woman has an incurable disease.

Prior to the 2002 law change, access to abortion was severely restricted, only permitted in pregnancies that threatened a pregnant woman’s life. The law was changed by necessity: Nepal’s maternal mortality ratio in 1996 was an astronomical 539 deaths per 100,000 live births.

The leading driver of these high rates? Complications from unsafe, illegal abortion, accounting for more than half of maternal deaths in hospitals.

To implement the new law, Nepal began offering safe abortions in government-run health clinics in each of the country’s 77 health districts. Today, those services are offered free of charge, as are a variety of methods of contraception.

In a dramatic turn, Nepal became a kind of poster child for successful policy change in reproductive health and rights: By 2016, Nepal had cut its maternal mortality ratio down to 239 deaths per 100,000 live births (a massive improvement, but still significantly higher than the Southern Asian average of 176 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births). The modern contraceptive prevalence rate climbed from 26 percent in 1996 to 43 percent in 2016. And the fertility rate dropped by half, from 4.6 to 2.3 children per woman.

Unsafe Abortion Persists Due to Stigma and Inaccessibility

Despite the aforementioned progress, nearly half (45 percent) of pregnancies in Nepal are still unintended. Nearly one-third of all pregnancies end in abortion. And the majority of abortions in Nepal are still unsafe. Of the roughly 323,000 abortions performed in 2014, more than half (58 percent) were of the self-administered or back-alley variety, causing more than 63,000 women to seek medical treatment for complications. Perhaps unsurprising, women in Nepal have a 1-in-167 chance of dying from maternal causes during their lifetimes.

Here’s the crux of the problem: Most Nepalis don’t know abortion is legal, never mind how to access it for free at government health clinics. Even if they do know, they have to get themselves to the clinic, which is no easy feat in a Himalayan nation. For many Nepali women, seeking medical care requires a multi-day trek across mountainous terrain.

And then there’s the stigma.

This is especially true for young, unmarried women and girls. Sajja Singh, the 23-year-old Vice President of YUWA, a Nepalese youth-led organization that educates on sexual and reproductive health and rights, explains:

Going to a safe abortion site takes huge courage. I’ve seen it myself. So I know that. They question. It’s your fault that you are pregnant. Most of the youth, they don’t prefer the government sites for safe abortion, because they feel it’s not confidential, or they might judge, or they might see someone they know. So they prefer to go to these private clinics that were funded by the United States. If they go to the safe abortion site, they will be asked, Are you married or not? The Nepali community believes in sex after marriage. Abortion is done after marriage. Before marriage is stigma. So what I’ve found is most of the women who come to the government sites are married. And they come with their husband or their relatives. It’s very hard for young people to go to the government site, all alone, unmarried. There is that judgmental look: Oh, she is unmarried, and she is coming for the safe abortion. Adolescents or teenagers may come, but either they are married, or they have children. At the age of 18, they have a three-year-old child. So they come with their husband to abort. I’ve seen no cases of an adolescent girl coming by herself to abort.

That bears repeating. During a month of conducting research at a peri-urban government clinic that provides abortion care, Sajja did not observe a single case of a childless, unmarried adolescent seeking a government-funded abortion.

Young people these days are entirely dependent upon the internet. They see everything. And they don’t realize every video is not to be followed, to be practiced. So they do unsafe abortions. Pierce rod inside vagina. Herbal medicines that are totally inappropriate. Beat on stomach.

Sajja describes meeting a 16-year-old girl at the clinic, five months pregnant, who was “kind of married.” (She said she was married.) She was accompanied by someone—not a relative. It was too late in her pregnancy to get an abortion, so she would have to carry it to term.

I asked if she knew about family planning, and she said no. I asked if she knew about condoms. She said yes. I asked, Why didn’t you go take condoms? She said, I’m shy. I’m shy. So young people are shy. They have this fear they will be judged. The condom is not to be talked about openly. The pharmacist will judge. Such kind of mentality has definitely led to more pregnancies among young people.

Bridging the Gap in Services Through Mobile Outreach

Even in cases of rape, with government documentation and advocates present, the government system can break down due to poorly trained staff.

Sajja observed a rape survivor in her mid-thirties who came to the government clinic for an abortion. Nepal has “one-stop crisis management” centers for rape survivors. Police sent details of the case to the clinic in advance. The survivor was accompanied by an advocate from the crisis center. When she arrived, there was a “rush of people.” But the doctors and nurses didn’t want to get mired in a complex legal case. Sajja explains:

Because it was a police case, the health providers were reluctant to provide the service. Because they require all details. They didn’t even enter the name of the client. They said it is a very risky case, we cannot handle it.

If a survivor, accompanied with police documentation and a government representative, is being refused legally mandated care, that is a gap in the system.

That’s where nurses like Babita come in. They offer welcoming, non-judgmental care, and train staff at government medical outposts to do the same. Building that trust is often the only way the most marginalized people will ever seek services—from teen girls to elderly women. Sometimes that means practitioners like Babita becoming a patient’s strongest advocate.

It’s not only victims of sexual assault that Babita advocates for. She recalls facilitating a cervical cancer screening clinic in a rural area. Such clinics normally focus on women ages 30 to 60, but “Reshma,” an 80-year-old woman, came a long way for a “gynie” (gynecological) exam.

Babita’s clinic helper did not want them to waste equipment and time on Reshma. Don’t see her! If we see her, that’s one instrument we can’t use on other people.

But Babita thought otherwise, and invited her in. Come grandma, and sit.

Reshma said she had never used any form of family planning. Never in my whole lifetime. But when Babita did the exam, she found a thread, and then something pricked her finger. She called in the attending doctor. There was an IUD in Reshma’s uterus. So old was the model of IUD, the 54-year-old doctor had never seen one. A throwback to times when women were sterilized or given IUDs without consent. “That mother didn’t even know she used the family planning method,” Babita marvels.

In mobile camps, they offer a range of services, from contraceptive education to pregnancy tests to “gynies.” They give special emphasis to providing the full range of contraceptive options, including longer-acting forms of contraception like vasectomies and IUDs, often preferable to rural couples hoping to avoid the long commutes to top up their contraception.

Trump’s Global Gag Rule

Nurses like Babita are fighters. Where the health and wellbeing of her patients is concerned, Babita does not like being told what to say—or what not to say—or which services she can and can’t offer.

This dedication to comprehensive care clashes with funding rules from Washington, DC. When asked about Trump’s Global Gag Rule, Babita isn’t familiar with the term. But when prompted by a list of restrictions on talking about abortion, the light bulb goes on: “I know about that.”

Whether or not she knows the name of the policy or the letter of the law, she certainly grasps the spirit of Trump’s Global Gag Rule: “We don’t speak about abortion because the funding is from the U.S. We have to control our mouth.”

A key part of the mobile clinics Babita ran was pregnancy tests and options counseling. Many unsuspecting women were shocked to discover unwanted pregnancies during these tests. Babita says:

We know each and every thing about abortion, but again that compliance comes in. With the U.S., compliance is we should not speak about abortion. At that time, I feel bad. We should have the right to give counseling, you should go for safe abortion. But we don’t want to talk. Because the compliance.

She tried to talk around the issue, as best she could. “I tell them to consult there. Another medical person. Consult with them.” She waives in the general direction of the central clinic in Kathmandu.

I cannot. I don’t want to speak, because of compliance and our project doesn’t work on abortion. So please, I don’t want to say those things. I don’t want to write that I have talked about abortion. So you consult with them…

Babita waves her thumb again, pointing to a general “elsewhere.”

Already distressed, patients’ confusion would escalate to desperation. And Babita could say nothing.

They are so upset. They say, Please tell me. A little bit awareness about abortion. I don’t know where to go. I’m afraid. If I don’t say anything to them, what do they do? Where will they go? For unsafe abortion…because U.S. funding does not allow us to talk about abortion. We need abortion. Because if they can’t get the safe abortion service, obviously with an unwanted pregnancy, they will go for an unsafe abortion anyhow.

As of January 2020, Babita has seen countless friends and colleagues lose their jobs with FPAN. You might think her transfer to the Kathmandu headquarters would be a sweet relief for Babita. No more tongue-biting, playing dumb, citing compliance to suicidal teen girls. It isn’t. Her heart is in rural outreach. She still misses working in the villages, with the women and girls who need her most.

And Babita is just one nurse working for one program. Says Sajja Singh of YUWA:

There are so many organizations funded by the United States. There are clinics that used to be run by the funds, but these clinics are now on the verge … they lack staff, they don’t have the medication and the equipment, they are not functioning like before. Due to the Global Gag Rule, the clinics … most of them are hardly functioning. So they are seeking alternative sources of funding. But clinics are being shut down. People are bound to choose unsafe abortion. Women’s lives are at stake.

Meanwhile, anti-abortion activists in Nepal concede that the Global Gag Rule will do little to curb abortions in their country. In a 2019 report on the impacts of Trump’s Global Gag Rule in Nepal[1], an anonymous anti-choice NGO director is quoted saying, “Other countries will bridge the gap it has created. European nations will support if America doesn’t. I don’t think this policy will make a massive difference.” According to the report, the respondent also “showed concern towards poor women who might seek out unsafe abortion due to the closure of clinics as the result of this policy.”

[1] Early Impacts of the Expanded Global Gag Rule in Nepal, CREHPA and IWHC

Investment Outcomes

Modern contraceptive use in Nepal already prevents an estimated 799,000 unintended pregnancies, 524,000 abortions, and 400 maternal deaths each year. If the 44 percent of women who currently have an unmet need for family planning began using modern contraception, health outcomes would improve immensely: There would be 469,000 fewer unintended pregnancies, 306,000 fewer abortions, and 300 fewer maternal deaths each year.

But instead of scaling up the U.S. investment in life-saving family planning programs in Nepal, Trump’s Global Gag Rule is cutting the U.S. government investment. FPAN lost its U.S. funding in November of 2018 ($5.5 million) and has since closed four clinics, reduced services at 29 more, and laid off 150 staff and 270 volunteers. Krishna Prasad Bista, the director general of FPAN, estimates that FPAN will now only be able to provide half the services each year that it had been providing before the Global Gag Rule.

Babita and Saraswati are only two of the hundreds of health care providers who have been impacted by Trump’s Global Gag Rule in Nepal. And the stories they told me about their patients are only a few examples of the stories of the 10 million people Krishna Prasad Bista estimates will be affected by the FPAN funding cut. That represents a third of Nepal’s population. Imagine: 10 million people’s health care being directly threatened by one person sitting in the White House, 7,700 miles away.

When talking with these brave, dedicated, hardworking women, I couldn’t help but think of that photograph taken of Donald Trump signing the Global Gag Rule into law, surrounded entirely by middle-aged and elderly white men. Men who knew nothing of the suffering their policy would cause. Men who perhaps didn’t—and still don’t—care about causing suffering to poor and marginalized people around the world.

Come to think of it, perhaps it is not Babita and Saraswati who should control their mouths, but, rather, Donald Trump and the members of his administration.