Deforestation: Still moving in the wrong direction

Written by Olivia Nater | Published: June 30, 2023

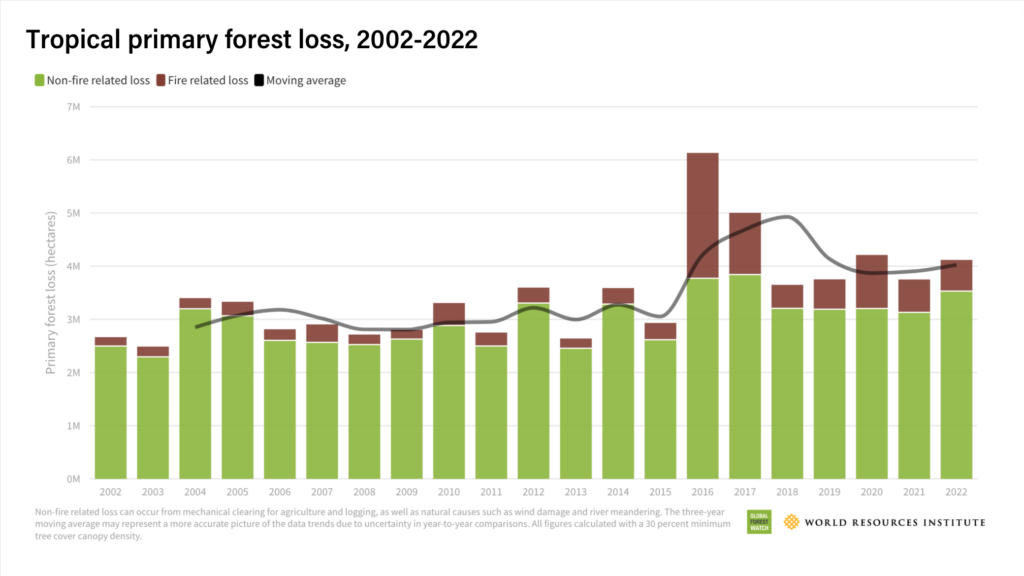

New data reveals 4.1 million hectares (approximately 10.1 million acres) of primary rainforest were destroyed in 2022 — a ten percent increase since the year before, with dire consequences for the climate, communities, and biodiversity. Having pledged to end deforestation by 2030, world leaders are clearly not doing enough to meet this goal.

The report by the World Resources Institute (WRI) says the loss produced 2.7 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions — roughly equal to India’s annual emissions, the third highest of all countries, after China and the United States.

While temperate and boreal forests also experience deforestation and, increasingly, fire losses, almost 97% of forest removal by humans (for agriculture and urbanization) this century occurred in the tropics. Tropical forests represent key carbon sinks and biodiversity hotspots, and provide livelihoods for more than a billion people.

The biggest losers

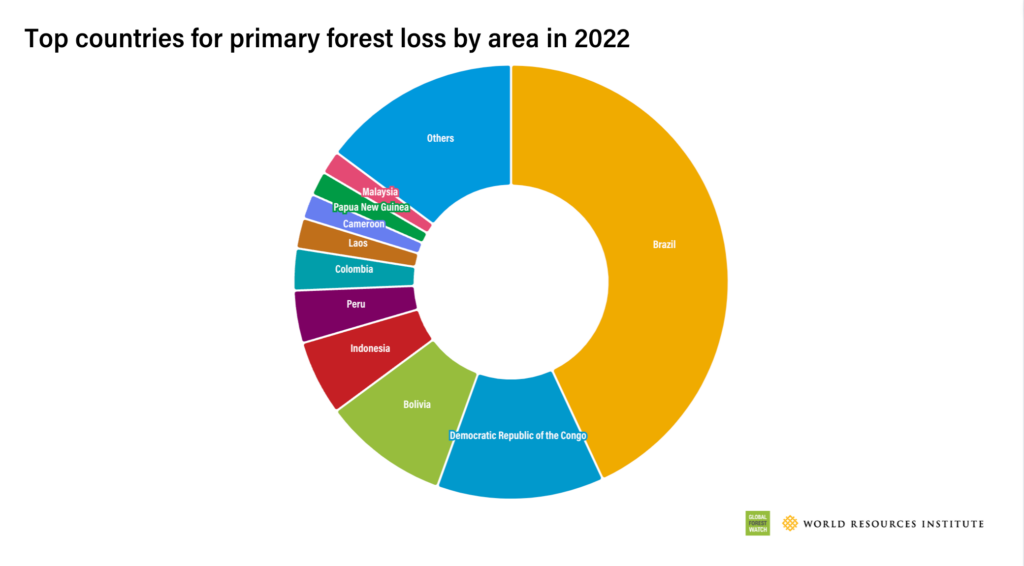

The majority of primary (old-growth, mature) forest loss occurred in Brazil (43.1%), followed by the Democratic Republic of the Congo (12.5%), Bolivia (9.4%), and Indonesia (5.6%).

A separate analysis of the data estimated that deforestation in the Amazon in 2022 was the second highest on record, behind a peak in 2004. Brazil’s rate of primary forest loss increased by 15% from 2021 to 2022. This was the last year of President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, which stripped away environmental protections and weakened Indigenous land rights, making it easier for damaging industrial activities to expand.

In the early 2000s, under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula), deforestation rates dropped dramatically, and his recent re-election offers hope for Brazil’s rainforests: President Lula has promised to end deforestation in Brazil by 2030.

Beef and soy production (mainly to feed livestock) are the leading causes of global tropical deforestation, including in Brazil and Bolivia, which experienced its highest forest loss ever recorded. In Indonesia, palm oil production is the biggest culprit. Demand for palm oil and meat has soared over the past 50 years, driven by population growth and rising incomes.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) lost over half a million hectares of rainforest in 2022, with the rate of loss continuing to increase. The biggest driver is small-scale agriculture and logging for charcoal production, which together accounted for as much as 84% of forest loss in the Congo Basin between 2000 and 2014 — see Population Connection’s June magazine issue for an in-depth exploration of deforestation in the Congo Basin.

The WRI report notes,

“DRC’s growing population is increasing demand for food, leading to shorter fallow periods and the expansion of agriculture into primary forest.”

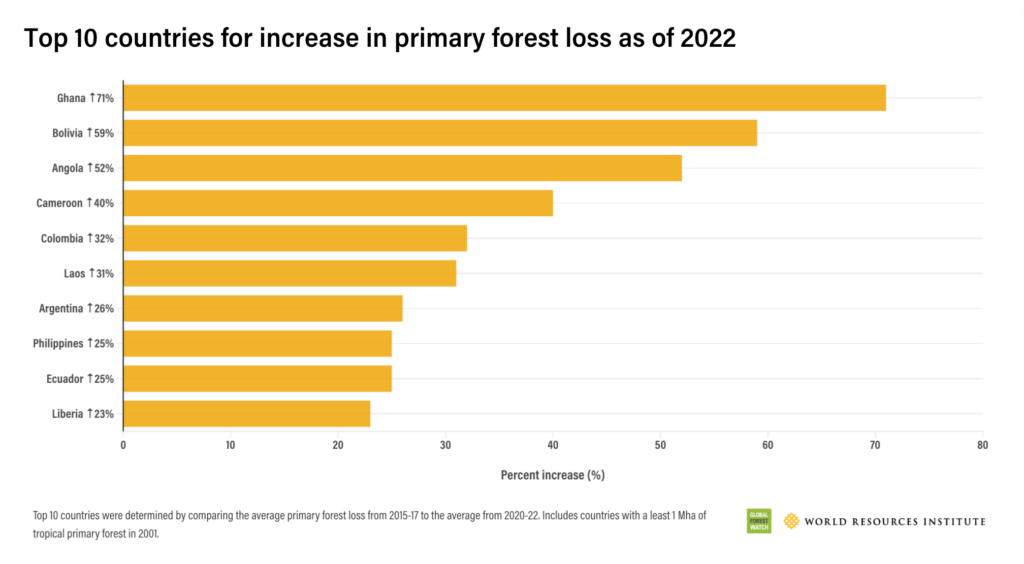

Ghana, Bolivia, Angola, Cameroon, and Colombia were the biggest losers in terms of their increase in primary forest loss in 2020-2022 relative to 2015-2017.

Ghana saw the largest proportional increase in primary forest loss of all countries, up by 71%. In 2022, this country — approximately the size of the United Kingdom — lost 18,000 ha, the majority within protected areas, which contain the last fragments of Ghana’s primary forest. WRI’s data suggest most of the loss is associated with cocoa production, as well as fire, and gold mining.

The biggest winners

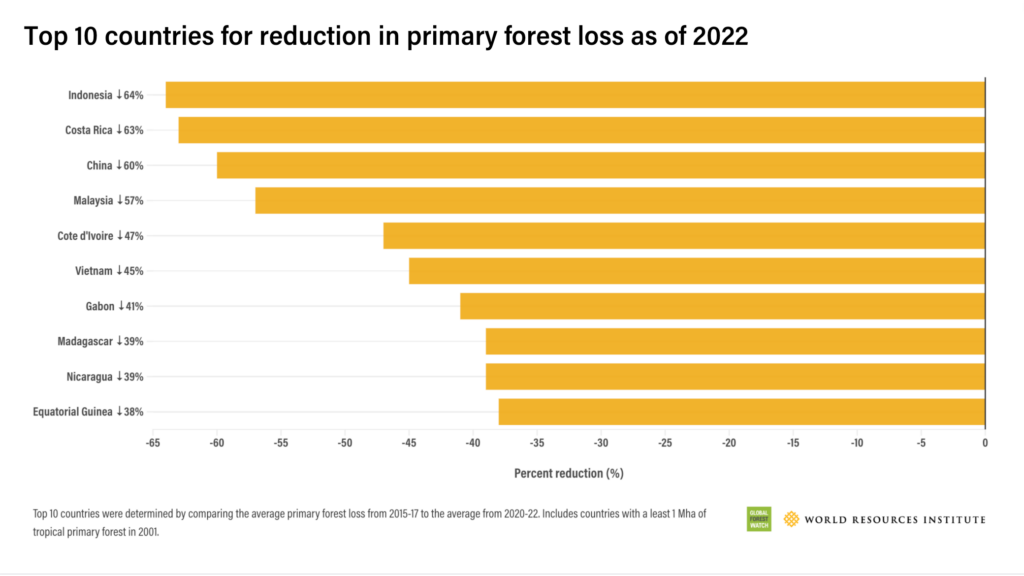

Indonesia is both a loser and a winner, as despite having incurred the fourth greatest amount of forest loss in 2022, it has also reduced its primary forest loss more than any other country in recent years. Indonesia’s forest loss dropped by 64% in 2020-2022 relative to 2015-2017 — the WRI report states that government policies have contributed to this reduction, in line with Indonesia’s target of turning forestry and other land use sectors into net carbon sinks by 2030. Successful measures include increased fire prevention and monitoring, a moratorium on new licenses in primary forest or peatland, law enforcement, and efforts to restore mangroves.

Costa Rica, China, and Malaysia also saw a significant drop in primary forest loss. Costa Rica is widely hailed as an environmental champion for reversing its deforestation rate thanks to the introduction in the 1990s of a country-wide ban accompanied by financial incentives for landowners to conserve and restore forests.

Even Costa Rica’s forests are far from safe, however — according to estimates, around a third of the country remains cattle pasture, and previously reforested areas have undergone a new round of deforestation. A 2018 study found that in the southern part of the country, half of regenerated forest patches had been cleared again within 20 years.

Making lasting progress

At the 2021 COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, the heads of 145 countries vowed to halt and reverse forest loss by the end of the decade, yet we are still moving in the wrong direction.

Ultimately, as with other environmental issues, we can only end deforestation for good if governments tackle its root driver: the growing human enterprise. Stabilizing human populations globally and cutting back on the consumption of environmentally-costly commodities like beef and palm oil, as well as reining in destructive corporate interests, are critical to achieving zero deforestation. We desperately need healthy forests to fight climate change, mitigate its impacts, and preserve biodiversity and livelihoods.