Written by Marian Starkey, Vice President for Communications |

Published: January 21, 2022

There’s been much written since the 2020 Census and 2020 CDC births data were released, about desired vs. actual fertility, i.e. how many children Americans say is ideal vs. how many they themselves end up having by the time their reproductive years have ended. The tone of these articles (examples here, here, and here) tends to be one of concern that women are having fewer children than they’d like to have.

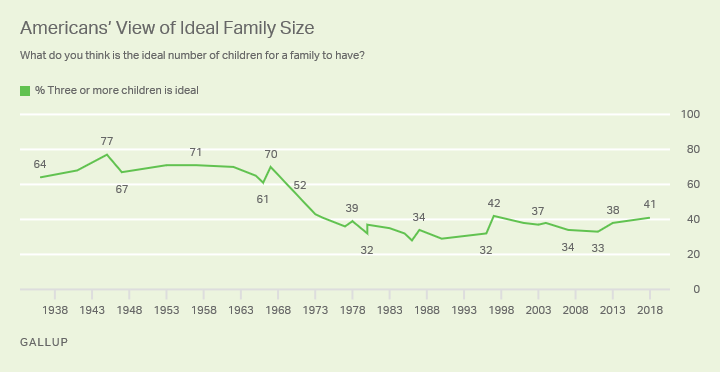

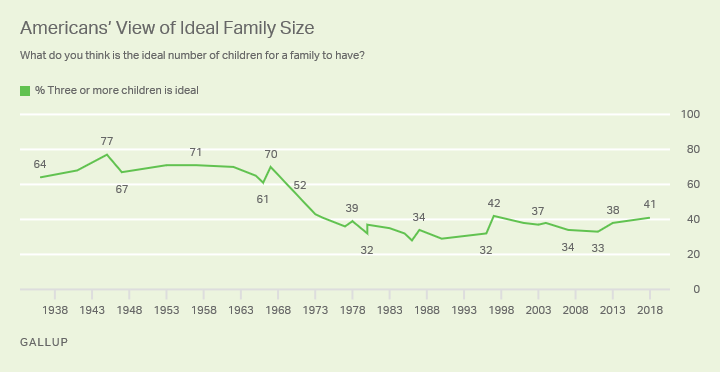

Many of these articles cite a Gallup poll, conducted every few years, which asks the question: “What do you think is the ideal number of children for a family to have?” When last measured, in 2018, the average answer was 2.7 (the current U.S. total fertility rate is more than a full child less than that, at 1.64 births per woman).

As someone who is eternally grateful for having a sister who I admire, respect, and enjoy spending time with, I might answer the Gallup poll by saying that two children are ideal for a family to have—after all, having a sibling has enhanced and added meaning to my life.

But that is a very different matter from how many children I myself want to have—which is none. Same goes for that fabulous sister of mine—no kids in her future either.

Like many of my childfree friends, I fall squarely into the demographic of people who have low fertility in this country: I’m a non-Hispanic white woman, have a graduate degree, make an upper-middle-class salary, don’t practice any religion, and live in the northeast. I also happen to be in an 18-year marriage to a wonderful man and have a deep love for other people’s babies and children. I can only imagine how the reality of having one’s own children could be less appealing or feel more out of reach for people who are single, struggling financially, or not crazy about kids in the first place. And yet, people who fall in those categories could still reply to the Gallup poll that two, three, or four children are ideal.

Frank Newport, Senior Scientist at Gallup, says, “[T]hese data reflect Americans’ perceptions of an idealized state of affairs and not what individuals think might be best for themselves personally.” And Lydia Saad, Director of U.S. Social Research at Gallup, says, “Americans, including young people, still embrace the idea of multiple children making for an ‘ideal’ family. Whether they ever strive for that ideal in their own lives is a different question.”

Whether to have children is the most consequential decision most of us will ever make, and preferences change over time and as life circumstances evolve. Treating childbearing like a decision made at one moment in time (when responding to a survey) doesn’t reflect most people’s lived reality. Some women assume they’ll have children and then the desire never strikes. Some try and aren’t able to conceive or carry a pregnancy to term. Some don’t meet a suitable partner in time. And yes, some would like to have a child or more children but don’t because of cost—this is the barrier that most of the articles I’ve seen have focused on alleviating.

I am all for making childrearing more affordable, most importantly because it improves so many critical outcomes for kids. President Biden’s American Families Plan brought that scenario closer to reality for so many and halved child poverty in the months after it was introduced. But creating national policy for the express purpose of raising fertility rates is a futile and misguided exercise. Whenever pronatalist policies have been introduced, whether in Hungary, Russia, or Singapore, people have generally responded by saying thanks, but no thanks. After all, a cash subsidy doesn’t equalize the burden of domestic work between mothers and fathers. It doesn’t make pregnancy or childbirth easier on women’s bodies. It doesn’t avert the reduced lifetime earnings of women who enter the “mommy track.” And it doesn’t give people their leisure time back to pursue interests outside of parenting.

Perhaps the Gallup question should be rewritten to ask people in their mid-late 40s: “Do you wish you had had more children than you actually had, and if so, what stopped you from having your ideal number?” That might give us a more accurate picture of where American policies and safety nets are falling short vs. to what extent low fertility is simply an inevitable result of cultural and societal progress.