Water is an essential resource for all life on Earth, yet our rapidly growing population, combined with worsening climate change, is threatening fresh water supplies. While water scarcity is hitting the world’s most vulnerable communities the hardest, wealthy countries are not spared. On World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought, we look at how parts of the U.S. are running dry and what we must do to avert a water crisis and an even drier future.

Record heat and drought

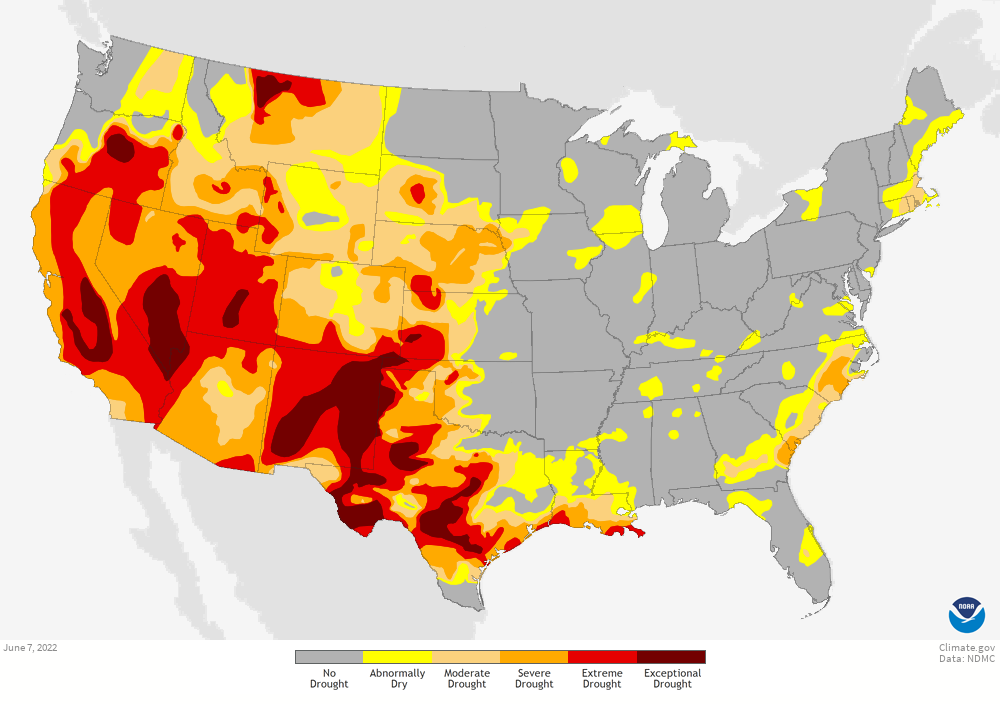

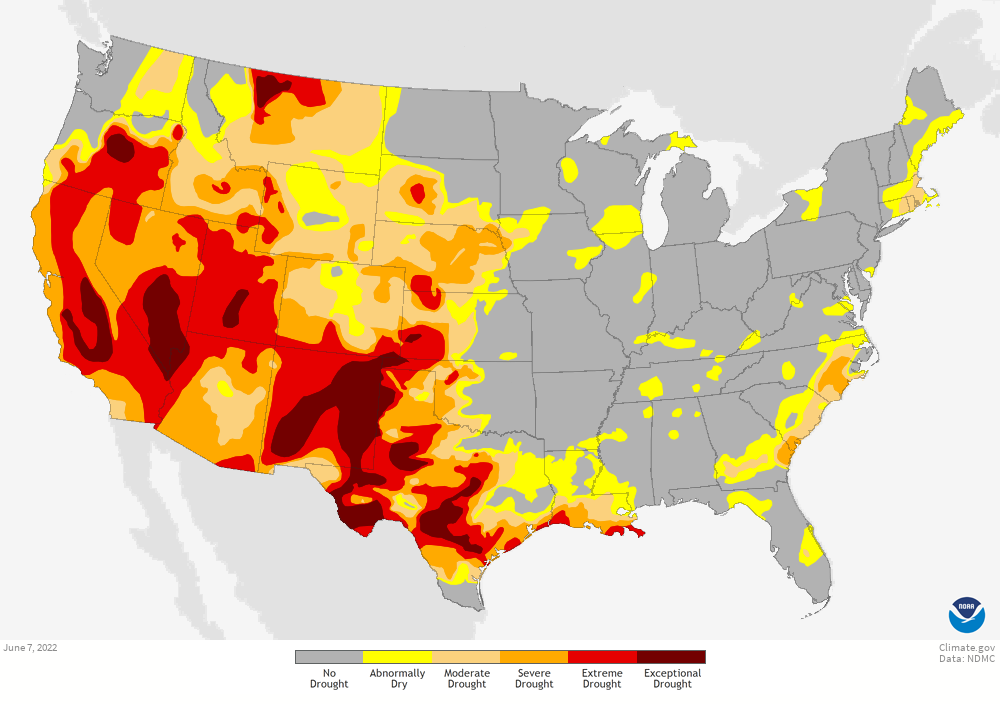

You may well be sweating as you read this, as more than 125 million people, almost 40% of the US population, are currently under heat alerts due to unseasonably high temperatures. While posing a direct threat to human health and survival, increasing temperatures are also leading to worsening drought, especially in the already arid Southwest, which is in the grip of an unrelenting ‘megadrought‘. Scientists estimate that 2000–2021 was the driest 22-year-period in the region since 800 AD.

Climate models predict that US droughts will continue to worsen over the coming decades, which is particularly concerning as water demand is likely to increase under continued population growth. Many of the southwestern cities facing the worst dry spells and water shortages, such as Las Vegas and Phoenix, also have some of the fastest-growing populations in the country.

Shrinking reservoirs, grim warnings

Lake Mead — the nation’s largest reservoir, formed in the 1930s through the construction of the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River — made headlines recently because its water level has dropped so low that bodies of long-lost murder victims are beginning to surface in previously submerged barrels. It’s hard to imagine a more grisly climate warning. Even more worrying, if the lake continues to shrink, it will eventually reach the rather fittingly named ‘dead pool’ status, meaning its level will be too low for the Hoover Dam to deliver water downstream or produce hydropower. Lake Mead now stands at only 28% of its former level, and Lake Powell, the country’s second largest reservoir, is only 27% full.

The Colorado has been a poster child for drought and over-extraction for decades, yet last August was the first time the US government declared a water shortage on the river. With reservoir levels continuing to break record lows and 40 million people dependent on the Colorado River for their water supply, federal water officials are now pushing for an emergency deal to protect what’s left.

The Colorado has been a poster child for drought and over-extraction for decades, yet last August was the first time the US government declared a water shortage on the river. With reservoir levels continuing to break record lows and 40 million people dependent on the Colorado River for their water supply, federal water officials are now pushing for an emergency deal to protect what’s left.

In Utah, Great Salt Lake is also dwindling dangerously fast as the region’s population expands. The lake has already shrunk by two-thirds, and Salt Lake City’s water demand is expected to exceed current supply by 2040. Like Lake Mead, Great Salt Lake also hides a dark secret that presents another pressing reason to prevent it from drying out — its lakebed is full of toxic heavy metals that can cause serious health issues when they become airborne.

Parched land

Aside from affecting vital fresh water sources, worsening drought is increasing the incidence and severity of wildfires and is exacerbating desertification, threatening our ability to grow food. Desertification occurs when poor land management practices, such as over-grazing, over-cultivation, and deforestation, combined with climate change, degrade arable land to the point of making it infertile, as demonstrated by the devastating Dust Bowl in the 1930s. Desertification and land degradation are a growing concern around the world, as population growth increases demands on agriculture and climate change makes those increasing demands harder to meet.

Scaling up water conservation

Drought-stricken cities must implement more sustainable water management and encourage mindful water use in homes — for example, green lawns may look pretty to some, but they have no place in a desert, not to mention that they have zero biodiversity value.

Domestic water use is just a drop in the bucket of overall water extraction, however. Agriculture uses by far the biggest share of water in the US, exceeding 75% in many basins, including the Colorado. More than half of the water extracted from the Colorado River basin is used to grow feed for livestock instead of crops for human consumption. An obvious yet rarely mentioned solution is to decrease our production of meat and dairy by ending subsidies for overproduction and reducing our per capita consumption of animal products, which is among the highest in the world. Scaling back livestock farming also happens to be one of the best things we can do to curb emissions and protect biodiversity.

Runaway climate change and water scarcity do not have to be our reality — we must ramp up efforts to end our reliance on fossil fuels and decarbonize our economies, stabilize our global population, and end overconsumption and waste, both in the US and globally.

The Colorado has been a poster child for drought and over-extraction for decades, yet last August was the first time the US government

The Colorado has been a poster child for drought and over-extraction for decades, yet last August was the first time the US government