The lone and level sands stretch far away: Confronting desertification

Written by Olivia Nater | Published: June 5, 2024

Today is World Environment Day, an annual UN observance day aimed at increasing awareness of and mobilizing action on environmental issues. This year’s focus is land restoration, desertification, and drought resilience, tying in with the upcoming World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought, observed on June 17. These themes are becoming increasingly relevant and pressing in light of the climate crisis and the ongoing expansion of human numbers and activities.

A sandy legacy

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

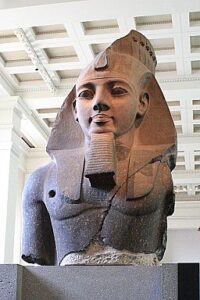

Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s famous sonnet “Ozymandias” (first published in 1818) is a reminder of the ephemerality of power and how time eventually reduces even major empires to dust. Ozymandias was the Greek name for the pharaoh Ramesses II, and the poem was inspired by archeological remains found in Egypt at the time. Ramesses II is thought to have lived between 1303 and 1213 BC, ruling during the peak of the ancient Egyptian empire’s power. But the image of once-thriving civilizations turning into nothing but sand is also highly relevant for this year’s World Environment Day.

Egypt is a lot drier now than it was during pharaonic times, and some scientists think that the entire Sahara Desert may have been verdant until around 8,000 years ago, before the expansion of pastoralism, which may have led to overgrazing.

Land degradation and desertification are happening a lot faster today due to the combination of intensive agriculture, worsening climate change, deforestation, and water overextraction. Land degradation is the loss of soil fertility — degraded land is no longer able to support healthy plant growth and thus large human populations. In severe cases, land degradation can escalate to desertification, whereby the land turns into desert.

Egypt’s Nile Delta has always been of critical importance for food production. During the Pharanoic Era, the fertile soils along the Nile supported an estimated 3 million people. Since then, Egypt’s population has grown more than 38-fold, to around 114.5 million today. Satellite data show that Egypt is losing around 2 percent of its arable land every decade due to urbanization, while existing farmland is also increasingly being lost to land degradation and desertification.

A global crisis

Egypt is just one of many severely affected countries. According to the UNCCD, the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (whose 30th anniversary is this year), up to 40 percent of the planet’s land is degraded or degrading, and at least 100 million hectares (386,000 sq. miles, or about the entire size of Egypt) of healthy, productive land is lost every year.

Many of the areas that are experiencing the worst land degradation also have the fastest growing populations, which is exacerbating food insecurity. Under the UNCCD, over 130 countries have pledged to achieve “land degradation neutrality” by 2030, meaning human activity has a neutral or even positive impact on the land. Initiatives to restore degraded land and stop the expansion of deserts are widely recognized as critical, yet they haven’t seen much success so far.

A notable example is the Great Green Wall Initiative, an ambitious project launched by the African Union in 2007 to combat land degradation, desertification, and the negative impacts of climate change in the Sahel region of Africa. The movement aims to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land by planting a band of trees (interspersed with sustainably managed grass- and farmland) across the entire width of Africa, approximately 5,000 miles, from Dakar in the west to Djibouti in the east.

Running to (not even) stand still

As well as fighting land degradation and desertification, the Great Green Wall is intended to help sequester carbon and support millions of livelihoods. It’s supposed to be completed by 2030, but we are less than six years away from this deadline, and the most recent assessment estimated that only between 4 and 20 percent of the restoration target has been achieved so far. Not to mention that we would have to meet this very ambitious 100-million-hectare restoration target every single year just to achieve net zero land degradation on a global level.

Time to get real

Time to get real

While ecosystem restoration efforts are essential, they won’t do much good if we fail to stop deforestation and land degradation in the first place. We are still cutting down forests and losing fertile land much faster than we are trying to restore them. Just like with every other environmental crisis, the only way to truly end land degradation and desertification is to tackle the root cause — ecological overshoot driven by global human population growth and overconsumption of resources in rich countries. Let’s get serious about real, positive solutions and ensure that future generations inherit a healthy, fertile planet teeming with life.