UN survey shows overpopulation concerns are widespread

Written by Olivia Nater | Published: May 10, 2023

A UN-commissioned survey on people’s perceptions of human population size revealed that the most commonly held belief is that our population is too large. The findings were reported in UNFPA’s State of World Population 2023 report, which explores how some attitudes toward population trends can be harmful.

The online survey was conducted by international research and analytics group YouGov in December 2022 and polled close to 8,000 adults across eight countries — Brazil, Egypt, France, Hungary, India, Japan, Nigeria, and the United States.

Respondents were asked whether they think the current world population, as well as the national population in their country, is “too high,” “too low,” or “about right.” They were also asked the same questions about the global and their national fertility rate (described in the survey as the total number of children per woman).

Overpopulation as the majority view

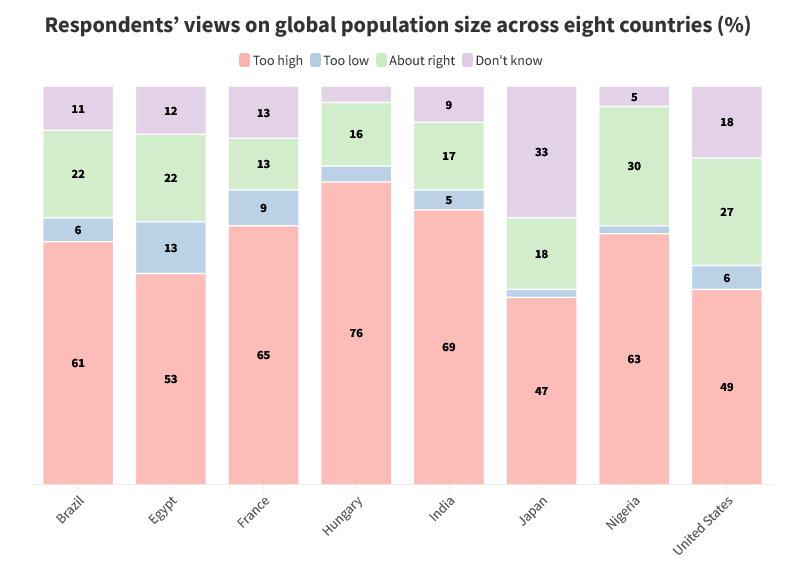

In all eight countries, the most common view among respondents was that the global population was too high. In six of the countries (Brazil, Egypt, France, Hungary, India, and Nigeria), this was the opinion of the majority of people — from 53% in Egypt to 76% in Hungary. Only a small minority of people across all countries said that they thought the global population was too low — from 2% in Nigeria and Japan, to 13% in Egypt. In the U.S., 49% of respondents said they thought the global population was too high, while only 6% said it was too low. Across all countries, between 13% (France) and 30% (Nigeria) said the global population was about right, while between 4% (Hungary) and 33% (Japan) said they didn’t know.

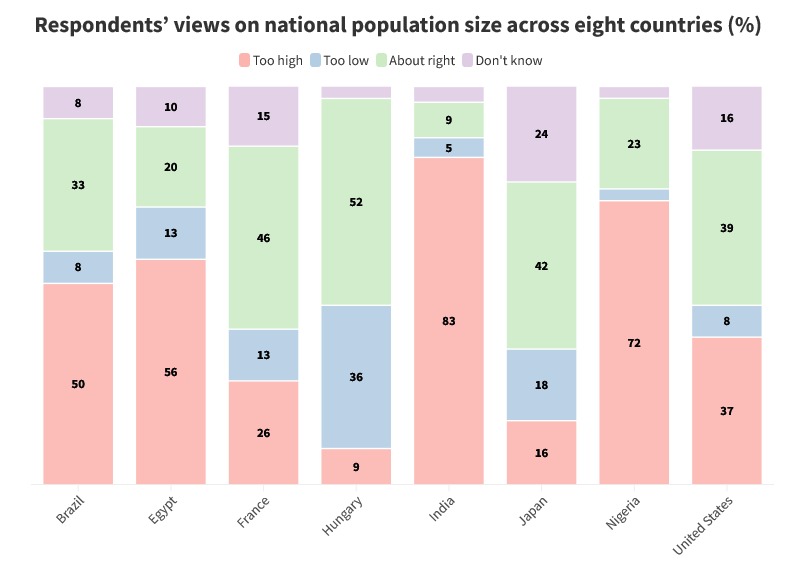

When asked about their own country’s population, “too high” was the most common response in half the countries — India (83%), Nigeria (72%), Egypt (56%) and Brazil (50%). In the remaining four countries, France, Hungary, Japan, and the U.S., the most common perception was that the national population size was about right. In Hungary, more than a third of respondents said their national population was too low.

These results were largely reflected in the responses to the questions on global and national fertility rates. In seven countries (all except Japan), the most common view was that the global fertility rate (currently at 2.3 live births per woman) is too high, ranging from 35% of respondents in India to 60% in France, while the second most common view was that it is about right. Only between 7% (France) and 18% (Egypt) said it is too low. Regarding their own country’s fertility rate, in Brazil, Egypt, India, and Nigeria, the most common view was that it is too high. In the U.S. and France, the prevailing view was that the national fertility rate is about right, while in Hungary and Japan, the most common perception was that it is too low.

People’s views align with the degree of population pressure their country is experiencing. The high proportion of people in India, Nigeria, Egypt, and Brazil saying their national population is too large, for example, is unsurprising considering all four countries have more than quadrupled in size since 1950 and are struggling to provide sufficient services, infrastructure, and jobs for their booming cohorts of young people.

The populations of Japan and Hungary, on the other hand, have been aging and shrinking for a while due to low fertility and emigration. Both governments have been framing this development as a big problem and have introduced policies to try to encourage couples to have more children, while paradoxically making it hard for people from other countries to immigrate. Hungary’s populist Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has been stoking the white nationalist “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory, espousing extreme anti-immigration views while spending vast sums to promote childbearing among heterosexual, Christian Hungarian women.

Media exposure and gender differences

The report’s authors found that in all countries, those who reported being exposed to media or conversations about the world’s population in the past 12 months were substantially more likely to view the global population as being too high.

The survey results also revealed an interesting gender difference: Men were more likely than women to view their national population as being too small, and more men than women thought lower domestic fertility rates would have a negative impact, while higher fertility rates would have a positive impact.

People worried about economic and environmental impacts

Respondents were also asked to identify up to three out of 20 issues related to population change that they deem the most important. Options included environmental, economic, human rights, and socio-cultural concerns, such as environmental impacts, increased competition for jobs, government restrictions on reproductive rights, and impacts on traditional culture.

Various economic issues were named as top concerns for the majority of people across all eight countries (from 60% in Egypt to 80% in Nigeria). Environmental concerns were the second most commonly cited priority in seven countries (from 34% in Egypt to 55% in Nigeria) — all except Hungary, where reproductive health policies and rights restrictions took second place. Rights restrictions were overall the third most commonly cited concern, with as many as 40% of respondents in Nigeria identifying them as an important issue.

Various economic issues were named as top concerns for the majority of people across all eight countries (from 60% in Egypt to 80% in Nigeria). Environmental concerns were the second most commonly cited priority in seven countries (from 34% in Egypt to 55% in Nigeria) — all except Hungary, where reproductive health policies and rights restrictions took second place. Rights restrictions were overall the third most commonly cited concern, with as many as 40% of respondents in Nigeria identifying them as an important issue.

Increase in pronatalist policies

Another analysis for the report looked into the number of governments adopting policies aimed at raising, lowering, or maintaining fertility rates over time. The authors report a “notable recent uptick” in these policies, especially those aimed at boosting fertility rates (pronatalist policies).

Predictably, the data show countries with high fertility rates (above the 2.1 replacement rate) mostly intend to use policy measures to reduce fertility rates. According to the UN’s 2021 World Population Policies report, in 2019, 69 countries had policies to lower fertility, with more than half of them in sub-Saharan Africa. Fifty-five countries (concentrated in Europe, Northern America, and Eastern and South-Eastern Asia) had policies aimed at raising fertility, and 19 had policies to maintain current levels of fertility. Overall, the countries with no fertility policies or policies aimed at increasing fertility rates tended to be the world’s wealthiest.

Population perceptions and targets inherently problematic?

The State of World Population report states that believing there are too many or too few people, or that fertility rates are too high or too low, is wrong, as are policies intended to change fertility rates. UNFPA argues that focusing on numbers creates a risk that policymakers will make decisions that lead to rights restrictions.

The authors state, “Over and over, we see birth rates identified as a problem — and a solution — with little acknowledgement of the agency of the people doing the birthing.”

They claim that all overpopulation rhetoric is harmful:

“Even when calls for limiting human reproduction are accompanied by caveats about respecting human rights, the overarching logic continues to allocate responsibility for reversing global scarcity, environmental degradation and climate change to those who have had the least chance to access opportunities, have contributed less to these problems given lower levels of consumption, and whose rights are most easily undermined.”

In a radical move away from UNFPA’s roots — the organization was founded in response to the challenges countries were encountering due to rapid population growth — the report argues that population concern portrays women’s bodies as tools to achieve a certain outcome.

At Population Connection, we disagree with this view — we believe bringing attention to the wider environmental and socio-economic benefits of women’s empowerment is key to leveraging the funding and policy action required to achieve gender equality. This is not the same as “allocating responsibility” for saving the world to underprivileged women and girls.

At Population Connection, we disagree with this view — we believe bringing attention to the wider environmental and socio-economic benefits of women’s empowerment is key to leveraging the funding and policy action required to achieve gender equality. This is not the same as “allocating responsibility” for saving the world to underprivileged women and girls.

The report laments the fact that overpopulation concern is still prevalent, saying that the seminal 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo reframed the population narrative around the need to ensure women have agency over their own bodies.

It goes on to ask:

“Why, then, are so many women still deprived of their bodily autonomy? The most recent data from 68 countries show that an estimated 44 per cent of partnered women are unable to make decisions over health care, sex or contraception. The result? Nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended,…”

Interestingly, several population experts argue that the “Cairo consensus” was actually responsible for the ensuing drop in funding for and deprioritization of international family planning.

In a 2008 presentation, Steven Sinding, Former Director-General of the International Planned Parenthood Federation, argued:

“I believe that without intending to do so, the architects of the Cairo consensus, as it is often called, transformed family planning from what had been seen as a global imperative to one among many desirable but non-essential public services. The crisis mentality that had sustained such high levels of support and so high a priority for family planning in the years before Cairo was no longer present at Cairo and it has almost entirely disappeared in the years since Cairo.”

Even though the Cairo consensus was entirely right to position women’s rights at the center of development efforts — especially in light of human rights violations perpetrated in the name of population control — an unfortunate unintended consequence was that world leaders no longer viewed improving access to contraception as a global imperative. The new mindset was essentially to “leave women alone,” without recognition that the status quo was deeply harmful for most women.

The fact is, women and girls around the world do need help. The report notes:

“Unmet need for contraception has barely fallen in decades, moving from 12.2 per cent in 2000 to 10.6 per cent in 2023 among partnered women. Looking forward, projections to the year 2030 indicate an increase in the number of women with a need for family planning to 1.2 billion and, because of population growth, 262 million women would still have an unmet need for modern contraception, up from the absolute number of 257 million in 2023.”

It also points out that “in the vast majority of countries with data, particularly in recent years, wanted fertility was noticeably lower than total fertility.” In other words, on average, women are still having more children than they would like.

Demonstrating how sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) are critical to achieving environmental and development goals is necessary to garner the attention and funding they deserve. It is possible to be concerned about population growth, and to recognize that ensuring women’s autonomy over their bodies and lives is the way forward.

The problems with “too few”

A population narrative in which women’s bodies are indeed viewed as a means to an end, without much regard for what women want, is that population sizes or fertility rates are too low. As revealed by the report, the number of countries with pronatalist policies is increasing as governments worry about the impacts of population aging. Fortunately, the report criticizes this mindset as well.

Policies that provide financial and other support for parents and would-be parents are beneficial to society, but the overall goal should not be to encourage people to have more children than what they decide is right for them. Some pronatalist policies are even coercive, taking choice away from people — for example, Afghanistan recently banned the sale of contraceptives.

Policies that provide financial and other support for parents and would-be parents are beneficial to society, but the overall goal should not be to encourage people to have more children than what they decide is right for them. Some pronatalist policies are even coercive, taking choice away from people — for example, Afghanistan recently banned the sale of contraceptives.

The report also explains why seeking to boost births to fight population aging makes little sense:

“Responding to an ageing population by encouraging people to have more babies, for example, ignores the fact that this will do little to relieve shortages of workers and pension burdens in the short term, and in fact will increase the need for other large investments like education long before the babies become productive, tax-paying workers.”

We need progressive, fact-based population concern

It’s simply unscientific to deny the impact population growth has on our environment, and on people’s quality of life. Further, ignoring the wider benefits of empowering women does not help anyone, as evidenced by its chronic underfunding.

The report admits that the goals of population and SRHR organizations are closely aligned:

“Both call for greatly expanding access to high-quality contraceptive services and information. Both call for investing in girls’ education and women’s economic empowerment. Both highlight the development benefits that accrue to societies and countries more broadly when individuals are able to responsibly plan their families, secure an education and invest in their children. Both also note the broad development gains that can be achieved in the years following fertility decline.”

It goes on to claim that “the two camps diverge” regarding who should make decisions. The authors state that reproductive agency is a secondary consideration for people concerned about overpopulation, but this is not true for progressive organizations like Population Connection: “Upholding sexual and reproductive health, rights, and justice so that people everywhere can live meaningful lives free of coercion and rooted in their own choices” is one of our core values.

We’re on the same side, and we all need to work together to kickstart the currently stagnating progress toward ending the unmet need for contraception and other injustices that prevent women from choosing their family size and exercising their full rights.