Upzoning: No Magic Fix to Affordable Housing Woes

Written by John Seager, President and CEO | Published: August 30, 2022

I live in Perkasie, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Population: 9,120. Our town is bisected by the East Branch of the Perkiomen Creek, alongside which you’ll find a Dairy Queen and our new amphitheater, where free concerts are held throughout the summer. Thanks to foresight and good fortune, our community has wonderful parks and recreation. You can buy a nice home here for about $300,000.

Perkasie enacted local zoning in 1937, inspiring our local newspaper to quip, “The Zoning Ordinance appearing elsewhere in this paper tells you where how and what kind of house or building you may erect in the future. In fact, nearly everything you want to know, except where to get the money to build it.”

Perkasie enacted local zoning in 1937, inspiring our local newspaper to quip, “The Zoning Ordinance appearing elsewhere in this paper tells you where how and what kind of house or building you may erect in the future. In fact, nearly everything you want to know, except where to get the money to build it.”

We were a bit late to zoning compared with New York City, which introduced it in 1916. Andrew Dolkart, professor of Historic Preservation at Columbia University, wrote, “The idea was that light and air would reach the sidewalk; light and air were a major issue.”

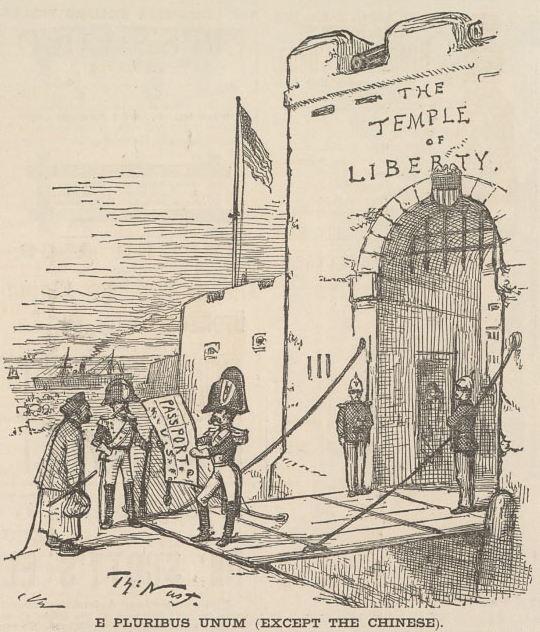

I’m fond of light and air, so those seem like sound driving factors. But efforts to regulate land use haven’t always been benign. In 1882, San Francisco effectively banned public laundries from most areas, which prevented many Chinese immigrants from engaging in their chosen enterprise. The Supreme Court blocked that effort four years later, citing Fourteenth Amendment guarantees of equal protection.

Zoning has variously reflected both aspiration and rank discrimination. It’s often fraught since, for many Americans, their home is their most cherished—and most valuable—possession.

Like zoning itself, efforts to increase density known as upzoning can be viewed from various perspectives. Affordable housing matters, but so does light and air, not to mention peace and quiet. Solutions often can’t be boiled down to the length of a tweet.

Lately in California and elsewhere, there has been increased focus on upzoning. We published a thoughtful blog post by a member of our Population Education staff on the advantages of upzoning. But, like many things in life, upzoning is not without its challenges and drawbacks. One warning flag comes from the enthusiastic support for upzoning by some affiliates of the Koch Brothers. It can be a Trojan horse used to decimate environmental regulation.

If the goal is affordable housing, upzoning may not be the most effective option. For example, a recent New York Times article about Atherton, CA, the richest ZIP code in America, quotes a developer’s claim that, due to the town’s high land costs, “affordable” units would sell for at least $4 million—beyond the pocketbook of most “middle class” Americans.

It’s been argued that “every new unit permitted in a wealthy place like Atherton eases price pressure on housing further down the market.” It seems improbable any such ripple effect would ever reach those priced out of decent housing. It’s quite possible that uber-wealthy people would just take the opportunity to add a fourth or fifth home to their portfolio by purchasing an Atherton condo.

One commenter in the Times story pointed out that “developers can’t make a profit if they have to provide infrastructure. So they want to build in towns that are already built out.” It doesn’t make much sense for developers to be rewarded for not paying their fair share of existing parks, schools, roads, and other infrastructure.

A Brookings article notes that “upzonings will fuel real estate speculation and gentrification, as landlords of upzoned buildings will be incentivized to sell their properties at inflated prices reflecting their added development potential.” Outside the relatively few communities with rent control, developers can use upzoning to replace now-affordable housing with higher density units beyond the financial reach of current tenants.

I’ve visited Atherton. It’s a lovely place. I’ve eaten lunch at the friendly local taqueria. But being able to afford a home would be far beyond my means, which is OK by me. As I write this, the least expensive home on the market in Atherton is a 1,650 SF “cozy ranch style home” on about one-third of an acre, with three bedrooms and two baths, priced exactly one dollar below $3 million. Atherton’s 2002 Plan seeks “to preserve the Town’s character as a scenic, rural, thickly wooded residential area with abundant open space.” Is that so terrible?

Recent changes in state law demand increased construction in many towns, including Atherton. There is strong local opposition to increased density there as in many other communities. Back East, a proposal has been put forward in Connecticut that could allow communities seeking to avoid upzoning to provide financial support to less-well-off communities. Some argue that this would let wealthier communities off the hook. Yet it might benefit more people now priced out of the housing market. That could be a “win” for families in need. Isn’t that what matters most in terms of meeting affordability challenges?

If some developer proposed a high rise building next to my home in Perkasie, I’d lead the charge against that effort. But I’m fine with the car repair shop right behind my house and the small apartment building two doors up the street. What makes sense in Perkasie may not be what works in Atherton. We can strive for the greater good while respecting our complex diversity.

It’s worth keeping in mind that one great way to make life better and simpler for all is to reduce population pressures and remove barriers to having smaller families. For all the hand-wringing about ostensibly damaging impacts from slower population growth, if there are fewer people competing for housing, it stands to reason that prices might decrease over time. With 3.7 million U.S. births in 2021, and with more than a third of U.S. births unintended (37 percent, according to a 2012 CDC survey of new mothers), we can estimate that there were over 1.35 million unintended births in 2021. With a shortfall of 7 million affordable homes, imagine what a difference it might make if we could substantially reduce unintended births, while also investing in programs that help people escape poverty. We might well accomplish more than “one-size-fits-all” efforts at upzoning.