Will the new global biodiversity agreement halt the extinction crisis?

Written by Olivia Nater | Published: December 22, 2022

On Monday morning, nations agreed on a major new plan to save the world’s biodiversity. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) aims to protect 30% of all land and marine areas by 2030 but is lacking in many areas, including on tackling root drivers of nature loss such as rapid population growth. Here’s a rundown of the framework’s strengths and weaknesses.

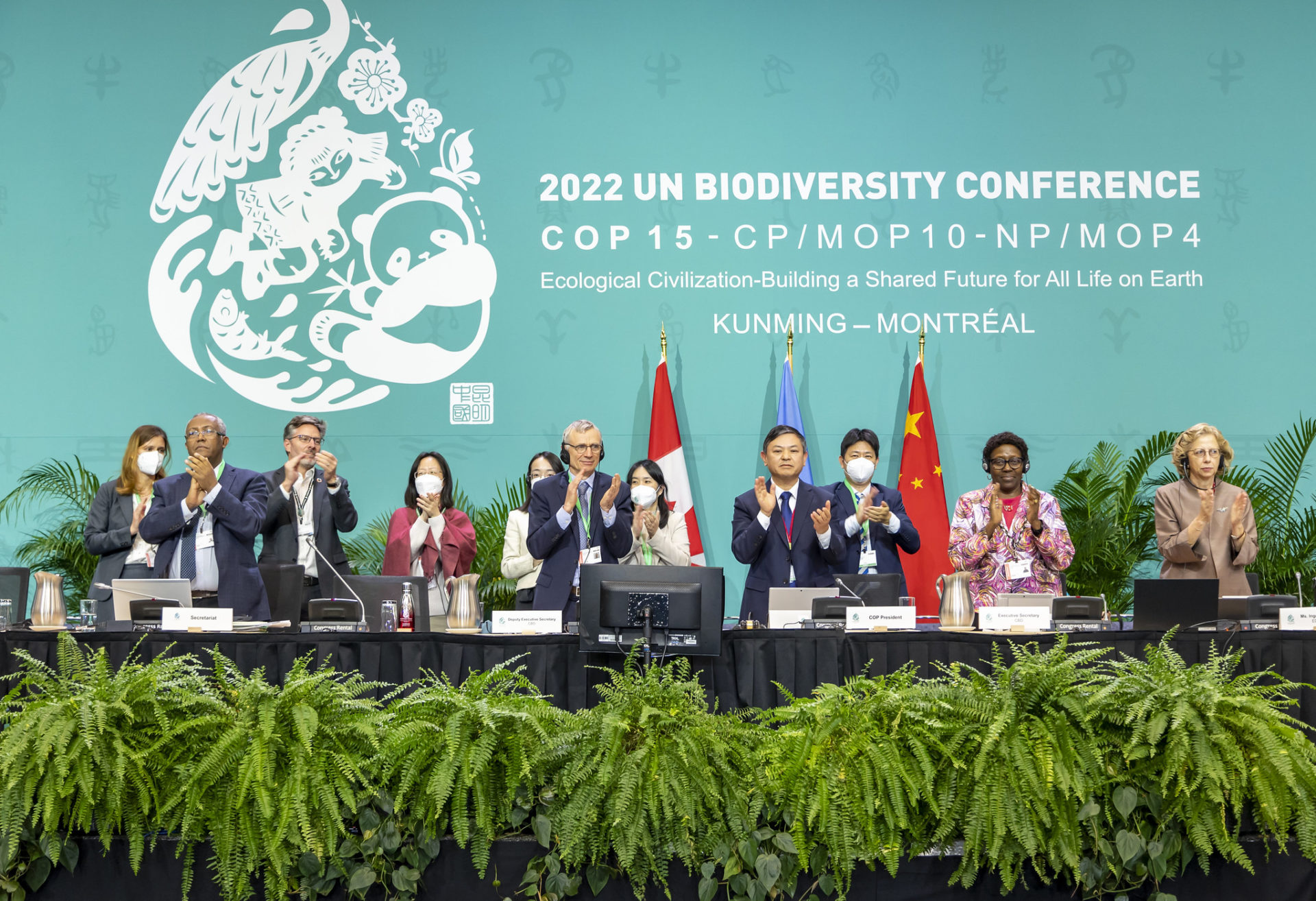

The agreement came out of the long overdue COP15 of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (UN CBD), held in Montreal, Canada, from December 7-19. The meeting was originally supposed to take place in Kunming, China, but had been postponed several times due to Covid-19 and was eventually relocated.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres praised the deal, saying, “We are finally starting to forge a peace pact with nature.”

Due to Republican resistance to international treaties to protect the environment, the United States is one of only two countries that are not parties to the UN CBD (the other is the Vatican) and so was only able to participate from the sidelines.

A history of failure

The GBF consists of four overarching goals supported by 23 targets and will replace the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, which were set in 2010 and expired in 2020. Unfortunately, none of the Aichi targets, which included halting habitat loss, ending harmful subsidies, and sustainably managing natural resources, were met.

The GBF consists of four overarching goals supported by 23 targets and will replace the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, which were set in 2010 and expired in 2020. Unfortunately, none of the Aichi targets, which included halting habitat loss, ending harmful subsidies, and sustainably managing natural resources, were met.

The extinction crisis is still accelerating, with a million species at risk of disappearing before the end of the century. A report published earlier this year found that vertebrate wildlife populations shrank by an average of 69% in just five decades, from 1970 to 2018.

Unlike the Paris Agreement on climate change, the new GBF is not legally binding, which raises doubt that it will be any more effective than its predecessor. To improve the new framework’s chance of success, states agreed to implement a monitoring and reporting mechanism to regularly evaluate progress — details will be hashed out at the next UN CBD meeting, COP16, in Turkey at the end of 2024.

Protection and restoration

The commitment to protect 30% of land and seas by 2030, also known as the 30×30 target, is a welcome concrete target that, if met, would be a significant improvement. Currently, only 17% of terrestrial areas and 10% of marine areas are under protection. Nevertheless, some groups, including those influenced by E.O. Wilson’s Half Earth project, were hoping for a more ambitious 50% target. Another shortcoming of the 30×30 target is that protection is not clearly defined in the framework — different countries use different definitions, which could lead to “protected areas” open to damaging activities, such as livestock grazing. For example, the United Kingdom currently designates 28% of its land as protected but research shows that in fact only 5% is effectively protected for nature.

As a non-member of the CBD, the United States is not bound to the GBF, but upon taking office, President Biden signed an executive order that would similarly place 30% of U.S. land and waters under protection. Policies to support the domestic 30×30 goal are facing strong opposition from conservative groups, however.

As a non-member of the CBD, the United States is not bound to the GBF, but upon taking office, President Biden signed an executive order that would similarly place 30% of U.S. land and waters under protection. Policies to support the domestic 30×30 goal are facing strong opposition from conservative groups, however.

Another new target that would give biodiversity a much-needed boost if implemented calls for restoring 30% of degraded ecosystems by 2030. Only a third of marine areas and a quarter of land areas remain relatively undisturbed by human activity — regenerating damaged areas, such as through reforestation, represents an important step in restoring healthy ecosystem function and fighting climate change.

The framework also calls for reducing the overall risk from pesticides and hazardous chemicals by at least half, but critics have pointed out that what’s really needed is a commitment to reduce pesticide and chemical use, rather than “risk.” The text does not explain what exactly is meant by “risk”, making this a rather toothless target.

Funding progress and shortfalls

As at the COP27 climate conference held in Egypt in November, financing was a major sticking point at the COP15 biodiversity conference. In the end, nations agreed that by 2030, conservation funding from all public and private sources must rise to at least $200 billion per year. Included in this commitment is a contribution of $20 billion per year from wealthy to low-income nations, increasing to at least $30 billion by 2030, but still a lot lower than what some delegates from developing countries were pushing for.

Any increase in funding is progress, but the $200 billion figure falls way short of the roughly $844 billion a year by 2030 that is needed to effectively protect and restore nature, according to a 2020 report.

The world currently spends about $1.8 trillion annually on subsidies that harm ecosystems and wild species, including for fossil fuels and intensive agriculture. The GBF includes a target for reducing harmful subsidies by at least $500 billion per year by 2030, although many called for wording to phase them out altogether.

Indigenous rights recognized

An encouraging aspect of the new framework is that the rights of Indigenous people are acknowledged throughout the text, as well as the need to include Indigenous voices in decision-making. Thanks to Indigenous influence, even the term “Mother Earth” made it into the final agreement, which represents a small but hopeful step towards transforming our broken relationship with the natural world.

Vague wording and major omissions

Clear, quantitative targets are key to successful conservation measures, but most of the targets use vague wording, such as “significantly” and “substantially,” which leaves the door open to insufficient action.

Probably the biggest weakness of the GBF is that it fails to adequately address the root causes of biodiversity loss. Ecological overshoot is a result of unsustainable population pressure and consumption patterns. The framework does aim to “reduce the global footprint of consumption” and to “encourage and enable sustainable consumption choices” but doesn’t call for specific measures other than halving global food waste by 2030.

Many have said the agreement should have specifically mentioned the need for widespread adoption of plant-based diets, seeing as overfishing is the most important threat to marine species, and habitat loss is the leading cause of biodiversity decline globally — agriculture is by far the biggest driver of habitat loss, and 77% of all agricultural land is used for rearing livestock.

Many have said the agreement should have specifically mentioned the need for widespread adoption of plant-based diets, seeing as overfishing is the most important threat to marine species, and habitat loss is the leading cause of biodiversity decline globally — agriculture is by far the biggest driver of habitat loss, and 77% of all agricultural land is used for rearing livestock.

Importantly, despite the undeniable negative impact of human population growth on nature, the GBF does not once mention it, nor the need to leverage empowering solutions like universal access to family planning and education. While the agreement aims to “ensure gender equality in the implementation of the framework,” both the GBF and the post-2020 Gender Plan of Action to support it fail to recognize that advancing women’s rights in itself represents a powerful conservation measure.

Will it work?

Ultimately, any global plan to halt biodiversity loss will only be successful in the long-term if it tackles all drivers. The new GBF is certainly better than no international agreement, and hopefully it will at least help slow the extinction crisis, but as with the climate crisis, nations must keep increasing their ambitions and confront the root causes: overconsumption and overpopulation. A more sustainable future is within reach, but it requires a profound transformation of our societies: normalizing more sustainable lifestyles in wealthy nations and ensuring that everyone, everywhere is free to choose a small family size.