Slower population growth is a good thing

Panic surrounding low fertility and population aging in the United States has become such a common theme in the news, one might expect readers to believe that we are suffering from a population collapse (a claim perhaps most famously and most frequently made by Elon Musk). Instead, a quick perusal of the comments section of any of these news articles will reveal that the majority of people who weigh in believe that population growth is unsustainable and must end. People intuitively understand that so many of the crises we face today, from housing shortages to suburban sprawl and the loss of natural spaces to regional water scarcity, are driven or exacerbated by population growth. They understand that the population cannot grow infinitely on a finite planet that’s already buckling under the pressure we’ve put on it over the past two centuries, during which our population has ballooned from 1 billion to over 8 billion.

Low fertility, population aging, and the workforce

It’s true that U.S. birth rates have declined — a sign that women have gained more agency over their own lives and bodies. The total fertility rate (the number of births a woman would have if current age-specific birth rates remained stable over the course of her lifetime) is currently 1.6 — well below the replacement rate of 2.1 (replacement rate fertility would keep the population stable in the absence of other demographic factors such as migration and changing age structure).

Growth rates vs. absolute growth

Despite the declining fertility rate, the United States population is still growing. In fact, it grew in 2024 at a higher rate (0.98%) than at any time in the past quarter-century, with the exception of 2001, when the U.S. population grew at 0.99%. The U.S. Census Bureau projects that the U.S. population will increase from 338 million in 2025 to 370 million in the 2080s. The increase will occur because of population momentum due to large numbers of women in their childbearing years, and because of immigration.

Teen pregnancy

It’s worth noting that one of the primary reasons for the declining U.S. fertility rate is the dramatic decrease in teen pregnancies since the 1990s — an inarguably positive development. And as long as we’re talking about birth rates and the economy, it’s relevant to mention that teen pregnancies and deliveries are disproportionately publicly funded, meaning that a reduction in teen pregnancies saves the government (and, by extension, taxpayers) money. This savings is magnified when considering the public costs associated with the myriad health and socioeconomic risks that teen parents and their children face.

The dependency ratio

Fears around slower population growth are typically rooted in changes to the “old-age dependency ratio” — the proportion of people who are older than 65, compared to those who are of “working-age.” The higher the dependency ratio, the fewer working-age people there are to support retired people, which is of particular concern because of the way our entitlement programs are set up (more on that below).

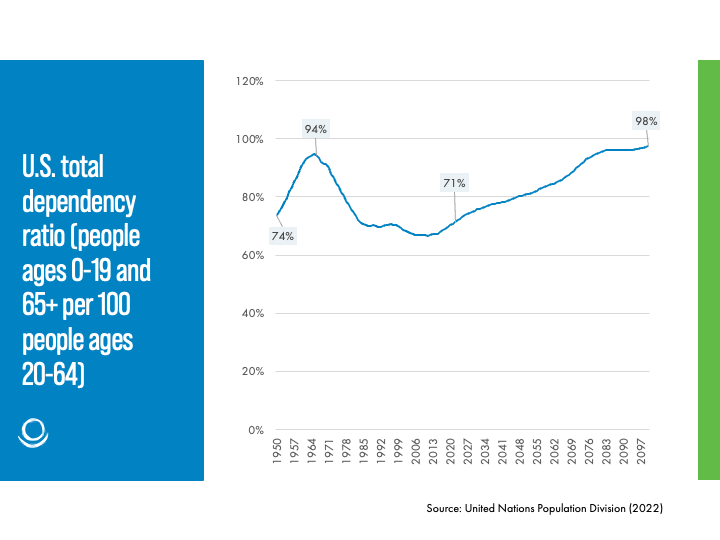

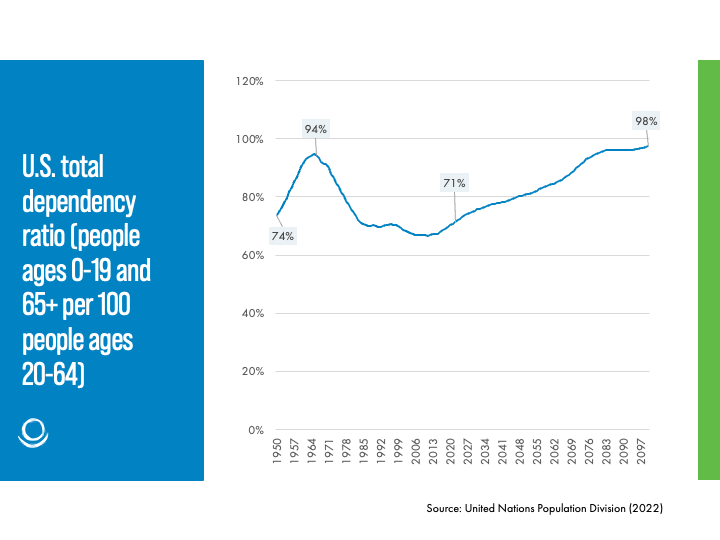

A better, more comprehensive measure is the total dependency ratio, which looks at elderly dependents (typically considered those over the age of 65) and at youth dependents (typically considered those under the age of 20). The total dependency ratio peaked in 1965 due to the baby boom, and it’s projected to rise to just above that peak level by the end of the century. In other words, we’ve been here before.

Higher birth rates, as prescribed by Elon Musk, J.D. Vance, and others of their ilk, would not have near-term positive effects on the economy. That’s because young people don’t tend to become economically productive until their early-to-mid-20s. An increase in the birth rate now would take up to 25 years to pay off. In the meantime, it would actually increase the total dependency ratio because the youth dependency ratio would rise.

A smaller youth population means lower expenditures on public services such as education (including higher education) and the children’s health insurance program (CHIP). It also — because much of the decline in birth rates is due to the drop in teen pregnancies — saves money on teens’ health care, since the majority of teenagers who give birth (78% in 2020) finance their deliveries via Medicaid. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and housing assistance also disproportionately serve teen mothers and their children. Finally, the children of teen mothers are twice as likely to be placed in foster care, and the sons of teen mothers are twice as likely to be incarcerated.

Entitlement programs were set up to depend on population growth

The Social Security and Medicare trust funds are “pay as you go” systems, meaning that today’s workers pay the benefits of today’s retirees. Without a growing population of workers, these funds risk insolvency. This may sound like a pyramid scheme, and it is — a population pyramid scheme.

Without policy changes, Social Security is projected to be depleted by 2033, and Medicare is projected to be drained by 2036. Exhausting these funds will result in benefits cuts for people drawing on them after these insolvency dates.

The variables used in Social Security projections are the fertility rate, the number of people receiving disability benefits, the level of labor productivity, and the employment rate of the working-age population. Medicare projections use all of these same variables, plus assumptions around future health care costs.

Given that all workers spend their careers paying into these two systems and expecting to be able to draw on them when they reach retirement age, it’s logical for there to be concerns around the ability of these two programs to continue to fund people’s benefits well into the future. Fortunately, there are several policy interventions that can alleviate the pressure on Social Security and Medicare, discussed in the next section.

Policy levers to prevent insolvency

In the absence of a growing population (which, to reiterate, the United States still has), there are ways to protect the economy from the effects of a growing dependency ratio. Here are a few, ranging from those that would increase human capital and improve productivity to those that would adjust the way benefits are funded:

Increasing the employment rate:

- This can be achieved by making it easier for parents, especially mothers, to join or remain in the workforce while caring for young children, through generous leave policies, flexible work schedules, and high-quality affordable childcare. It’s worth noting that women who have smaller families tend to have higher employment rates.

- Another group that has historically been excluded from participating in the workforce is people with disabilities. The unemployment rate for people with disabilities is around 10%, compared to around 5% for people without a disability. Various workplace accommodations could raise labor force participation among people living with disabilities.

- Finally, supporting seniors who would like to continue working would boost workforce participation, potentially delay the age at which they begin collecting Social Security benefits, keep them healthier and more engaged in their community, and allow employers to retain invaluable institutional knowledge that gets lost when they retire.

Improving workers’ health and technical skills:

- There are currently 11 million U.S. children living in poverty — many of whom will struggle to realize their full potential as adults. Ensuring that kids grow up living in safe neighborhoods, eating nutritious food, getting high-quality education, and avoiding teen pregnancy will set the best foundation for them to become productive workers when they reach adulthood (among countless other benefits to them, their future children, and entire communities).

- Improving the “health span” of older people will enable them to remain in the workforce longer and miss fewer days of work due to illness and injury.

- Prioritizing the training of current and future workers to have the technical skills that are necessary for the job market of today and tomorrow is crucial to raising worker productivity. Technical colleges and adult education programs can play an important role here.

Capitalizing on immigration to close workforce gaps:

- Immigrants tend to skew younger than the “native” populations they are joining. The disproportionate share of immigrants who are of working age can benefit the economies of receiving countries. This is especially true when considering that aging societies often have difficulty filling health and eldercare roles. Care workers from other countries can be critical to filling these important positions.

Raising the retirement age:

- Life expectancy continues to rise from where it was when Social Security and Medicare were created (1935 and 1965, respectively). Increasing the retirement age is an unpopular option but could be used to reduce the dependency ratio without necessarily reducing the number of years the average American spends in retirement (compared to past generations). For example, the average life expectancy at age 65 (the number of years the average 65-year-old is expected to continue living) was 14 years in 1950. Since then, it has risen to 20 years.

Social Security tax reforms:

- The revenue used to pay Social Security benefits comes from taxes on current workers’ wages (half is paid by employers, and the other half is paid by employees). However, not all income is taxed.

- The cap on wages taxed by Social Security is $176,100 in 2025. This means that any wages earned above this amount are exempt from being taxed by the Social Security program. Raising or eliminating the payroll tax gap would increase the program’s revenue and would make it more equitable. For example, someone currently making $176,100 pays 6.2% of their wages to Social Security ($10,918). Someone making $1 million pays the same absolute amount — $10,918 — which is only 1.1% of their total wages.

- Currently, wages reported on a W-2 are the only income taxed by Social Security. Expanding the tax base to include income such as interest, dividends, and capital gains would solve any present concerns around insolvency and would also make Social Security taxation more equitable, as those in the highest income brackets tend to rely less on wages for their incomes than do people who are in lower income brackets. “Taxing the expanded base could more than pay for promised Social Security benefits for 35 years and there would even be some money to eliminate poverty among all Social Security recipients,” [labor economist Teresa Ghilarducci of the New School] observes.

Whatever policy measures this country pursues to protect the economy as we transition to an aging and, eventually, slower-growing population, pushing women to increase the U.S. birth rate should not be among them. The population pyramid scheme must end at some point, and the sooner it happens, the better it will be for the planet and the future generations it must support.