Climate change is one of humanity’s most critical challenges. The warming of the planet threatens food security, freshwater supply, and human health. The effects of climate change, including sea level rise, droughts, floods, and extreme weather, will be more severe if actions are not taken to dramatically reduce emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere [1]. While the link between human action and the planet’s recent warming remains an almost unanimous scientific consensus, the links between population growth and climate change deserve further exploration [2].

In 2023, the global population surpassed 8 billion. With 1 billion people projected to be added to our human ranks by 2040 and an additional 1 billion more by 2060, demographic trends and variables play an important role in understanding and confronting the world’s climate crisis [3]. Population growth, along with increasing consumption, tends to increase emissions of climate-changing greenhouse gases. Rapid population growth worsens the impacts of climate change by straining resources. It also exposes more people to climate-related risks [4-8].

Including population dynamics in climate change-related education and advocacy can help clarify why improving access to reproductive health care, family planning options, girls’ education, and gender equity are important climate mitigation strategies. Increased investment in health and education, along with improvements in infrastructure and land use, would strengthen climate resilience and build adaptive capacity for people around the world [5, 9, 10].

EARTH’S TEMPERATURE IS RISING

Earth’s average temperature is higher than at any point in recorded history, with new temperature records now being set on a regular basis [11]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that human emissions of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, and nitrous oxide, have raised the global average temperature by 1.1°C (2°F) above pre-industrial levels [12].

To limit the risks posed by climate change, countries around the world agreed to hold the average temperature increase well below 2°C, aiming for a 1.5°C threshold [13]. If current warming trends continue, the Earth’s average temperature increase is likely to reach 1.5°C by the 2030s [1, 14]. Global warming above this level would significantly increase the risk and frequency of extreme weather events and damage to many of the planet’s terrestrial and marine ecosystems [12].

Holding the temperature rise to 1.5°C involves fundamentally changing the processes that produce the most greenhouse gas emissions, especially burning fossil fuels for energy, industry, and transportation. A global energy transition involving using energy more efficiently, generating it from renewable sources, such as solar and wind, and electrifying transportation would reduce emissions from coal, oil, and natural gas. This is especially relevant for high polluting areas such as the United States, Europe, China, and India [15]. Stopping forest loss, planting new forests, reducing food waste, and managing land to conserve soil carbon also are additional important steps to limit warming for both the industrial and developing countries.

POPULATION AND EMISSIONS LINKS

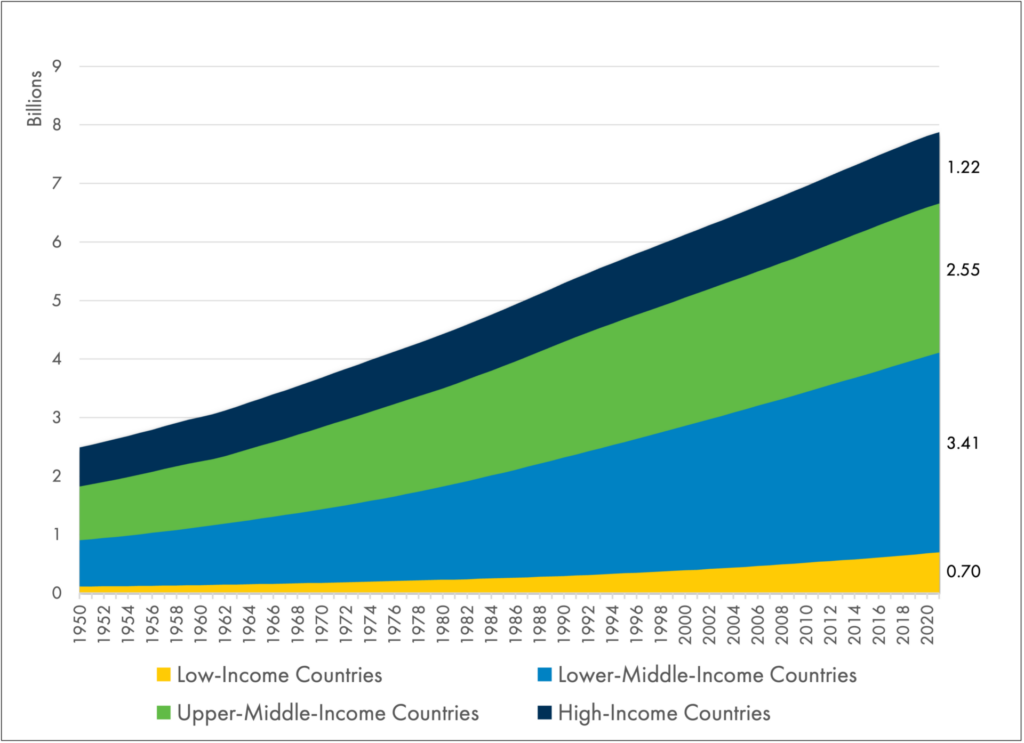

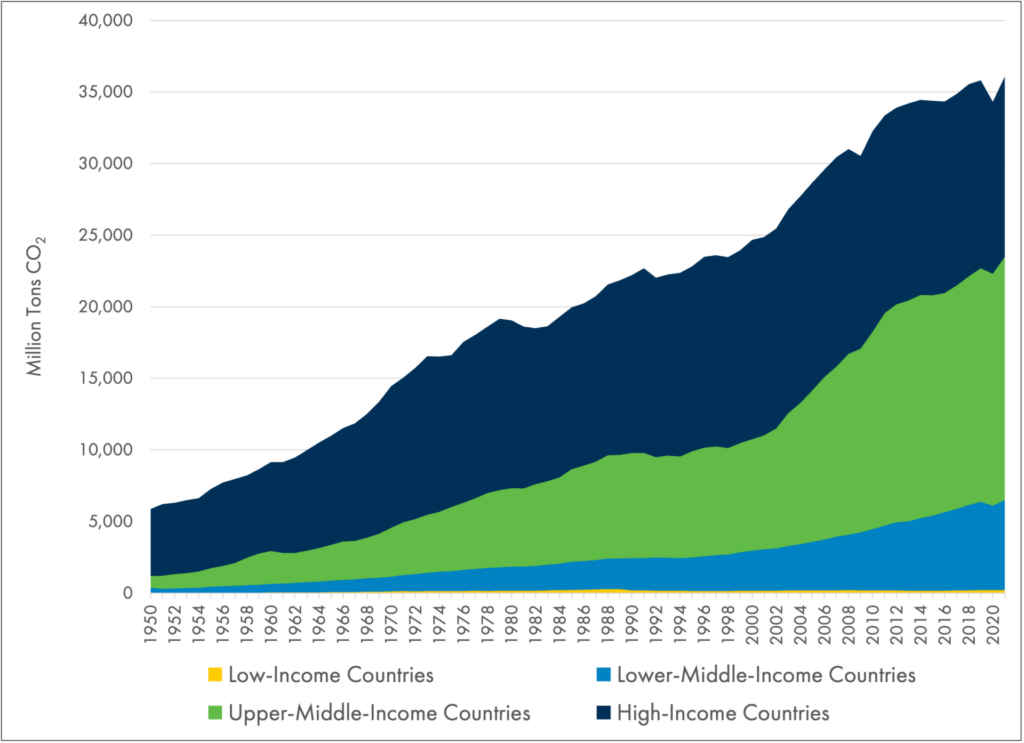

There has been a reluctance to integrate discussions of population into climate education and advocacy. Yet climate change is tightly linked to population growth. As the U.K.-based charity Population Matters summarizes: “Every additional person increases carbon emissions—the rich far more than the poor—and increases the number of climate change victims—the poor far more than the rich” [16]. At the national level, there is a clear relationship between income and per capita CO2 emissions, with average emissions for people living in industrialized countries and key oil producing nations topping the charts [17]. Consumerist lifestyles and polluting production practices in the highest-income countries result in much higher emissions rates than in middle- and low-income countries, where the majority of the world’s population lives (Figures 1 and 2) [3, 18-22].

For example, the United States represents just over 4% of the global population but accounts for 17% of the world’s energy use [3, 23]. Per person carbon emissions in the U.S. are among the highest in the world. People living in the United States, Australia, and Canada have carbon footprints close to 200 times larger than people in some of the poorest and fastest-growing countries in sub-Saharan Africa, such as Chad, Niger, and the Central African Republic [17]. In the middle of the spectrum are the middle-income economies, home to 75% of the world’s population [24]. In these places, industrialization likely will increase standards of living and consumption patterns over the coming decades [25, 26]. Without changes to how economies tend to grow—namely by decoupling rising affluence with carbon emissions—their contribution to global warming will rise.

As there is no panacea for climate change mitigation, a wide variety of options needs to be exercised. An integrated approach includes educating girls and empowering women to make their own decisions about reproduction [27].

FIGURE 1. GLOBAL POPULATION BY INCOME LEVEL, 1950-2021

FIGURE 2. CARBON DIOXIDE EMISSIONS BY INCOME LEVEL, 1950-2021

Examining the effects of different population growth rates on future economic growth and energy use shows that slowing population growth can significantly reduce future greenhouse gas emissions [4, 6, 7]. Incorporating various population projections into climate models shows that higher population growth typically results in higher emissions. For example, one study found that if the global population were to peak in mid-century and then shrink to 7.1 billion by 2100, carbon emissions could be as much as 41% lower than if the population continued to grow to 15 billion [28].

Even in scenarios of low population growth, however, carbon-intensive economic growth and technological choices can result in high emissions [9]. Nevertheless, a growing body of research indicates that slowing global population growth through rights-based measures, such as by increasing access to voluntary family planning services, can play a key role in mitigating climate change [4-7, 18, 28-30].

POPULATION AND CLIMATE VULNERABILITY

Despite contributing very little to overall emissions, people living in some of the world’s most impoverished regions are in a position to bear the brunt of climate change’s most disastrous impacts. High rates of poverty and social inequality leave many low-income populations vulnerable to the weather extremes, water stresses, and food production challenges associated with a warming climate [31]. This vulnerability can be affected by factors like urbanization, geography, land use, infrastructure, and access to capital [32]. The combination of climate change impacts and rapid population growth to regions already dealing with poverty and gender inequalities presents a humanitarian problem that will only continue to worsen if left unaddressed.

Low levels of education, gender inequality, and a significant unmet need for family planning information and services together lead to high levels of unplanned pregnancies. Globally, close to half of pregnancies are unintended [33]. In low- and middle-income countries alone, some 218 million women want to avoid pregnancy but are not using any form of modern contraceptives [34].

Population pressures pose challenges for the environment and for economic development, undermining food security, poverty alleviation, natural resource conservation, and human health prospects. The UN’s medium variant projection shows that the global population could grow to 8.5 billion in 2030, 9.7 billion in 2050, and 10.3 billion in 2100 [3]. The fastest growth occurs among the 46 Least Developed Countries (LDCs), many of which are projected to double in population by mid-century [35].

Under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, LDC governments can assess their vulnerability to climate change with the intention of identifying needs and appropriate actions in National Adaptation Programmes of Action [36]. The vast majority of these plans recognize rapid population growth as a key factor worsening climate vulnerability [36, 37].

The links between population growth and climate vulnerability are visible around the world. In Pakistan, population pressures have led to land clearing, which exacerbates flooding at the same time that more people have been crowded into flood-prone areas [38, 39]. In Afghanistan, multi-year droughts have compounded the ongoing stresses of conflict and economic collapse, forcing millions of people from their homes [40, 41].

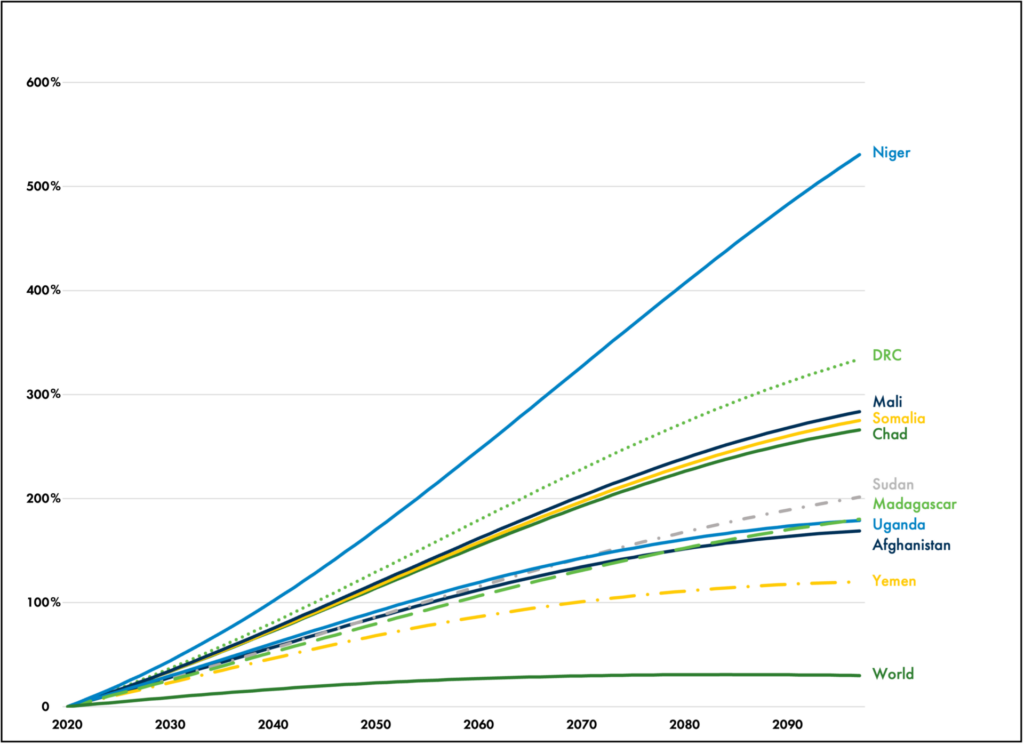

FIGURE 3. PROJECTED POPULATION CHANGE IN SELECTED COUNTRIES MOST THREATENED BY CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS, 2023-2100

Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to double in population by 2050—accounting for half the world’s population growth [3]. The region is home to many of the countries most threatened by the impacts of climate change [42]. People in Niger, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Somalia, and Chad are among those facing more frequent droughts, severe floods, extreme heat, and soil erosion, all amidst rapidly growing populations (Figure 3) [3, 42]. In Malawi, where 95% of agriculture is rainfed, severe droughts and floods hamper food production [43-45]. Climate change is expected to deliver more extreme weather events there, including both flooding and droughts. [45]

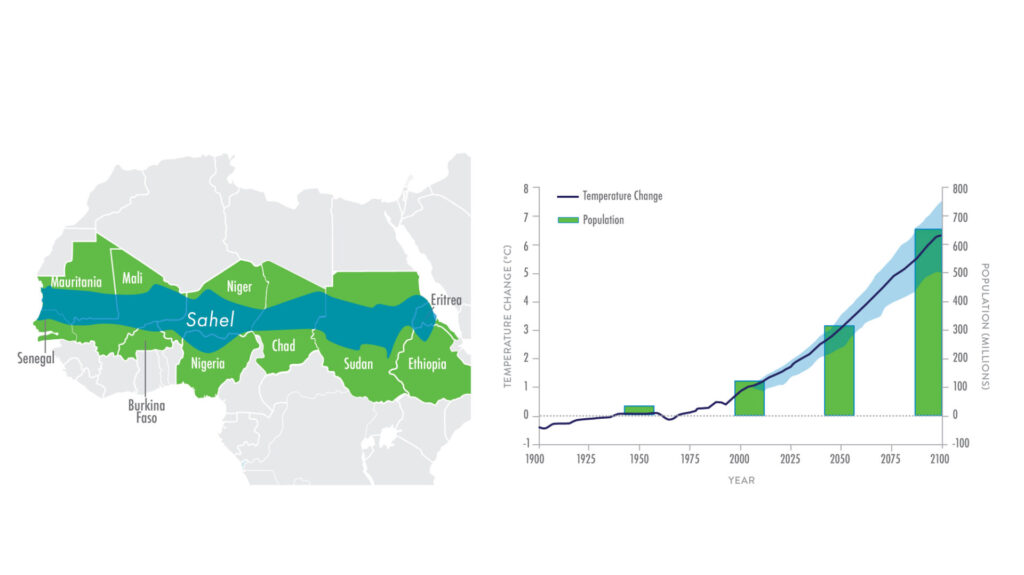

An extreme example can be found in sub-Saharan Africa’s Sahel region (Figure 4), where tens of millions of people already face food insecurity [46]. The Sahel population grew from 31 million in 1950 to 100 million in 2013. Projections show it reaching 300 million by 2050 and more than 600 million by 2100 [47]. Temperatures in the Sahel are rising 1.5 times faster than the global average [48]. Scientists project a temperature increase of 3–5°C by mid-century and by as much as 8°C by 2100 (Figure 5) [47]. As a result, increasingly frequent droughts and floods threaten to further impair food production in a region where over 80% of farmland is already degraded and growing populations are shrinking the pastureland available to each family [48, 49]. Hundreds of millions of people could lack sustainable food supplies in future decades.

FIGURE 4. THE SAHEL REGION, FIGURE 5. TEMPERATURE AND POPULATION IN SAHEL

Around the globe, climate change is increasing the variability of precipitation patterns, making water management more difficult [49]. High population growth rates compound the challenge as they shrink water supplies available per person. Water withdrawals from rivers and underground sources can outpace natural replenishment.

Currently, people in 25 countries, totaling a quarter of the world’s population, live with extremely high water stress [50, 51]. Many are in the Middle East and North Africa, where annual average population growth of 1.5% is nearly double the global average rate of 0.8% [19, 50]. In India, the world’s most populous country, water shortages pose a significant threat to the country’s 1.4 billion inhabitants. India encompasses nearly 18% of the global population but holds less than 4% of the world’s freshwater resources [3, 19, 52]. Agriculture in the densely populated country is heavily dependent on irrigation; however, rivers have been diverted and wells have been overdrawn to meet the food and water needs of the growing population. Groundwater depletion or contamination affects more than half of Indian districts, and underground water levels are falling by between 1-3 meters a year in key food producing states [52, 53]. As climate change alters the patterns of the monsoon rains and the frequency of droughts, tens of millions of people could be forced to migrate in search of fresh water [54-56].

While a warmer world will experience more water scarcity in some regions, flooding is also a threat, both inland and along coastlines, which also face rising sea levels and increased storm surge. Many of the world’s floodplains and coastlines are densely populated. Low-elevation coastal zones represent 2% of the world’s land area but contain well over 10% of the world’s population [57]. Of the world’s 31 megacities, 21 are along a coastline, and migration to the coasts is increasing [58]. As coastal and riverine populations grow, more people are at risk [5]. The World Resources Institute projects that the number of people affected by flooding will double between 2010 and 2030 [59].

UNMET NEED FOR FAMILY PLANNING

Population growth is seen as a potential barrier to meeting the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 [60]. These goals include ending poverty and hunger, ensuring access to clean water, achieving global gender equality, educating all children, stopping biodiversity loss and ecosystem destruction, and combating climate change. Rapid population growth stifles development by increasing hunger rates, resource use, greenhouse gas emissions, and species extinction [61, 62].

Human-rights-based policies that empower women, educate all children, and address unmet needs for reproductive health services in all regions of the world would reduce population growth rates through voluntary reductions in fertility. These changes, in effect, would help avoid future climate-changing emissions while fostering sustainable development and increasing capacity for communities to adapt to climate change impacts [5].

A woman’s ability to choose whether and when to bear children, as well as how many children to have over the course of her lifetime, is a basic human right. Empowering women can lead to poverty reduction and foster sustainable development [63]. It also creates a more equitable society over time. When people, in particular women and girls, gain access to education, they also gain political, economic, and social power. This facilitates economic growth, improves health and livelihoods, and delivers higher levels of bodily autonomy [64]. Women who are educated tend to have fewer children, and those that they bear are healthier [65, 66]. As individuals, families, and communities access higher levels of education and quality health care, these tools are passed onto subsequent generations [67]. Thus, the benefits of health and education compound over time [68]. Within the context of climate change, the additional health, education, and economic benefits afforded through family planning would greatly reduce climate vulnerability and increase resilience for women and families across the world.

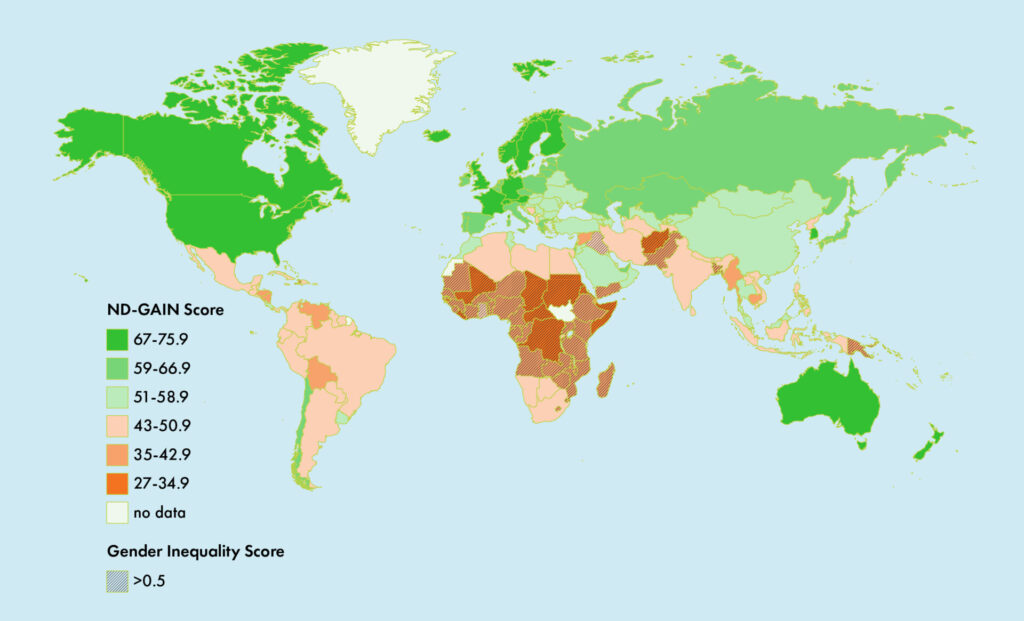

Many of the same regions of the world with high rates of poverty and pronounced vulnerability to the impacts of climate change also have high levels of gender inequality, where many women experience relatively low levels of reproductive health, education, empowerment, and participation in the labor market (Figure 6) [42, 69, 70]. Contraceptive availability and use tend to be limited. In much of the Sahel region, for example, fewer than 10% of women are using modern contraception [19, 47]. While surveys indicate that only 10% of Niger’s married women of reproductive age use modern contraceptives, about 20% have expressed an unmet need for family planning [19, 71]. Family size averages close to 7 children [3]. Nearly 45% of girls of primary school age do not attend school [72].

FIGURE 6. CLIMATE CHANGE VULNERABILITY AND GENDER INEQUALITY

Note: The University of Notre Dame’s ND-GAIN score indicates a country’s vulnerability to climate change impacts combined with its readiness to adapt. Higher values indicate less vulnerability and more readiness. The Gender Inequality Index from the United Nations Development Programme covers three dimensions: reproductive health, educational and political empowerment, and labor force participation. Scores range from 0 (perfect equality between women and men) to 1 (extreme inequality).

In the face of very real threats that a changing climate poses to food security, increasing access to voluntary family planning services and education can lower fertility rates and reduce pressures on food and water supplies, helping to better ensure that children do not go hungry. The UN medium projection showing the global population reaching 9.7 billion by 2050 assumes a fertility decline for countries where large families are still prevalent [35]. Without investments in family planning and the removal of barriers preventing people from accessing reproductive health care and schooling, the global population could grow much faster and climate resilience could be weakened.

INVESTING IN WOMEN AS A LOW COST CLIMATE SOLUTION

Global greenhouse gas emissions averaged a record 54 gigatons of CO2-equivalent per year between 2010 and 2019, over two-thirds of which came from fossil fuel burning. Keeping the global average temperature from exceeding 1.5°C in a cost-effective manner would require reducing global emissions by 45% by 2030 [73].

Research examining the potential impacts of increased investment in family planning found that funding family planning and girls’ education could prevent a cumulative 69 gigatons of CO2 emissions between 2021 and 2050 [74]. That scale of reduction is similar to what could be achieved by shutting down some 18,000 coal-fired power plants [75].

Family planning options could be provided in low-income countries at an annual cost of only around $10 per user [34]. The cost of avoiding emissions through investments in family planning comes out to about $4.50 per ton of CO2 [76]. Educating girls yields emissions reductions at close to $10 per ton of CO2 [77]. Both are cheaper than some other attractive emissions reduction options, such as wind and solar power (each less than $20 per ton), and represent a small fraction of outfitting new coal plants with carbon capture and storage technology (upwards of $95 per ton) [74, 76]. Investing in family planning and education is an incredibly cost-effective climate change solution—both in terms of upfront cost and return on investment. Fully meeting unmet needs for family planning worldwide could yield long-term health and economic benefits equal to $120 for each dollar spent on family planning [78].

The annual funding gap for meeting family planning needs worldwide is just under $6 billion [79]. Family planning programs receive well under 1% of international development aid [80, 81]. Increasing spending to fill the unmet need for family planning services will help improve lives and mitigate climate change. In addition, healthy and educated populations will be better equipped to weather the effects of climate change [82]. This much is clear: Efforts to address climate change must include increasing access to reproductive health care services, education, and family planning options.

“Honoring the dignity of women and children through family planning is not about governments forcing the birth rate down (or up, through natalist policies). Nor is it about those in rich countries, where emissions are highest, telling people elsewhere to stop having children. When family planning focuses on health care provision and meeting women’s expressed needs, empowerment, equality, and well-being are the result; the benefits to the planet are side effects.”

–Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming (2017)

Want to learn more about the relationship between population growth and environmental issues? Sign up to our newsletter!

ENDNOTES

- IPCC, Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield, Editor. 2018: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/.

- NASA. Scientific consensus: Earth’s climate is warming. 2023; Available from: https://climate.nasa.gov/scientific-consensus.

- United Nations. World Population Prospects database. 2023; Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp.

- Dodson, J.C., P. Dérer, P. Cafaro, and F. Götmark, “Population growth and climate change: Addressing the overlooked threat multiplier.” Science of the Total Environment, 2020. 748: p. 141346.

- Guzmán, J.M., et al., Population dynamics and climate change. 2009, https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/pop_dynamics_climate_change_0.pdf.

- O’Sullivan, J.N., Synergy between population policy, climate adaptation and mitigation, in Pathways to a Sustainable Economy: Bridging the Gap between Paris Climate Change Commitments and Net Zero Emissions, Moazzem Hossain, Robert Hales, and T. Sarker, Editors. 2018, Springer. p. 103-125.

- Population Action International. Why population matters to climate change. 2011; Available from: https://pai.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/PAI-1293-Climate-Change_compressed.pdf.

- Population Institute, Population and climate change vulnerability: Understanding current trends to enhance rights and resilience. 2023: https://www.populationinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Population-and-Climate-Change-Vulnerability.pdf.

- Riahi, K., et al., The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Global Environmental Change, 2017. 42: p. 153-168.

- Samir, K. and W. Lutz, The human core of the shared socioeconomic pathways: Population scenarios by age, sex and level of education for all countries to 2100. Global Environmental Change, 2017. 42: p. 181-192.

- NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, G.T. GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP), version 4. 2023; Available from: https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp.

- IPCC, Summary for policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Core Writing Team, H. Lee, and J. Romero, Editors. 2023: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/.

- United Nations. Paris Agreement. 2015; Available from: https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf.

- World Meteorological Organization. Global temperatures set to reach new records in next five years. 2023; Available from: https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/global-temperatures-set-reach-new-records-next-five-years.

- WMO, et al., United in science: High-level synthesis report of latest climate science information convened by the Science Advisory Group of the UN Climate Action Summit 2019. 2019: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/30023/climsci.pdf.

- Population Matters. Climate change. 2018; Available from: https://populationmatters.org/the-facts/climate-change.

- Ritchie, H. and M. Roser. CO₂ and greenhouse gas emissions. Our World in Data 2021; Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-other-greenhouse-gas-emissions.

- Satterthwaite, D., The implications of population growth and urbanization for climate change. Environment and Urbanization, 2009. 21(2): p. 545-567.

- World Bank. World Bank open data. 2023; Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/.

- Deuster, C., et al., Demography and climate change. 2023, European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, Publications Office of the European Union: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC133580.

- Ritchie, H., et al. Data on CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions by Our World in Data. 2023; Available from: https://github.com/owid/co2-data.

- Global Carbon Project. Global carbon budget: Data. 2022; Available from: https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/carbonbudget/22/data.htm.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. What is the United States’ share of world energy consumption? 2022; Available from: https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=87&t=1.

- World Bank. The World Bank in Middle Income Countries. 2019; Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/mic.

- OECD, Perspectives on global development 2012: Social cohesion in a shifting world. 2011, OECD: Paris.

- OECD, Perspectives on global development 2021: From protest to progress? 2021, OECD Publishing: https://www.oecd.org/development/pgd/.

- International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) and Population and Sustainability Network, Climate change: Time to “think family planning”. 2016.

- O’Neill, B.C., et al., Demographic change and carbon dioxide emissions. The Lancet, 2012. 380(9837): p. 157-164.

- Bongaarts, J. and R. Sitruk-Ware, Climate change and contraception. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health, 2019. 45(4): p. 233-235.

- Stephenson, J., K. Newman, and S. Mayhew, Population dynamics and climate change: What are the links? Journal of Public Health, 2010. 32(2): p. 150-156.

- Islam, N. and J. Winkel, Climate change and social inequality. DESA Working Paper No. 152, 2017.

- Jiang, L. and K. Hardee, How do recent population trends matter to climate change? Population Research and Policy Review, 2011. 30(2): p. 287-312.

- Baker, D., et al., Seeing the unseen: The case for action in the neglected crisis of unintended pregnancy, in State of World Population 2022. 2022, UNFPA: https://www.unfpa.org/swp2022.

- Sully, E.A., et al., Adding it up: Investing in sexual and reproductive health, 2019. 2020, Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- United Nations, World population prospects 2022: Summary of results. 2022, UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- UNFCCC. National Adaptation Programmes of Action. 2020; Available from: https://unfccc.int/topics/resilience/workstreams/national-adaptation-programmes-of-action/introduction.

- Hardee, K. and C. Mutunga, Strengthening the link between climate change adaptation and national development plans: lessons from the case of population in National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs). Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 2010. 15(2): p. 113-126.

- O’Sullivan, J.N. Population growth as a variable providing the single most powerful lever for minimising the extent of climate change and the negative impacts of climate change. Submission to UNFCCC Secretariat from Sustainable Population Australia 2013; Available from: https://unfccc.int/files/science/workstreams/the_2013-2015_review/application/pdf/spa_submission_to_sbsta_review_of_global_goal-march_2013.pdf.

- Sathar, Z. and K. Khan, Climate, population, and vulnerability in Pakistan: Exploring evidence of linkages for adaptation. 2019, Islamabad: Population Council.

- Sayed, N. and S.H. Sadat. Climate change compounds longstanding displacement in Afghanistan. Migration Policy Institute 2022; Available from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/climate-change-displacement-afghanistan.

- ReliefWeb. Afghanistan: Drought – 2021-2023. 2023; Available from: https://reliefweb.int/disaster/dr-2021-000022-afg.

- University of Notre Dame’s Global Adaptation Initiative. ND-GAIN country index. 2022; Available from: https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/rankings/.

- USAID. Climate risk profile: Malawi. ClimateLinks 2017; Available from: https://www.climatelinks.org/resources/climate-change-risk-profile-malawi.

- USAID. Climate risk profile: Malawi. 2017; Available from: https://www.climatelinks.org/resources/climate-change-risk-profile-malawi.

- World Bank. Malawi. Climate Change Knowledge Portal 2021; Available from: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/malawi/vulnerability.

- World Food Programme. Food insecurity and malnutrition in West and Central Africa at 10-year high as crisis spreads to coastal countries. 2023; Available from: https://www.wfp.org/news/food-insecurity-and-malnutrition-west-and-central-africa-10-year-high-crisis-spreads-coastal.

- Potts, M., et al., Crisis in the Sahel: Possible solutions and the consequences of inaction. A report following the OASIS Conference (Organizing to Advance Solutions in the Sahel) hosted by the University of California, Berkeley and African Institute for Development Policy on September 21, 2012. 2013: http://oasisinitiative.berkeley.edu/publications/2016/2/20/crisis-in-the-sahel-possible-solutions-and-the-consequences-of-inaction.

- Muggah, R. and J. Cabrera. The Sahel engulfed by violence, climate change, food insecurity and extremists are largely to blame. in World Economic Forum. 2019.

- IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, H.-O. Pörtner, et al., Editors. 2022, Cambridge University Press: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/.

- World Resources Institute. Aqueduct™ Water Risk Atlas (Aqueduct 4.0). 2023; Available from: https://www.wri.org/aqueduct.

- Kuzma, S., L. Saccoccia, and M. Chertock. 25 countries, housing one-quarter of the population, face extremely high water stress. 2023; Available from: https://www.wri.org/insights/highest-water-stressed-countries.

- Arcanjo, M., The future of water in India. 2019: Climate Institute.

- World Bank. Helping India manage its complex water resources. 2019; Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/03/22/helping-india-manage-its-complex-water-resources.

- Parth, M.N., India’s water crisis: Bundelkhand residents take to the road as water shortage forces migration, in Bloomberg Quint. 2019.

- Pundir, P., Expert says Indians will soon become water refugees heading for water-rich Europe, in Vice. 2019.

- Temple, J., India’s water crisis is already here. Climate change will compound it., in MIT Technology Review. 2019.

- Neumann, B., A.T. Vafeidis, J. Zimmermann, and R.J. Nicholls, Future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding-a global assessment. PloS one, 2015. 10(3): p. e0118571.

- Daigle, K. and M. Singh, As waters rise, coastal megacities like Mumbai face catastrophe. Science News, 2018.

- Kuzma, S. and T. Luo. The number of people affected by floods will double between 2010 and 2030. World Resources Institute 2020; Available from: https://www.wri.org/blog/2020/04/aqueduct-floods-investment-green-gray-infrastructure.

- UN News. UN highlights profound implication of population trends on sustainable development. 2019 April 1; Available from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/04/1035841.

- United Nations, Global population growth and sustainable development. 2021, UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/global-population-growth.

- FAO, et al., The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2018. Building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. 2018, U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome.

- UNFPA. Family planning. United Nations Population Fund 2020; Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/family-planning.

- Greene, M., S. Joshi, and O. Robles, By choice, not by chance: Family planning, human rights and development. State of the World Population, 2012: p. 128 pp.

- Yineger, N. and C. Greenbaum, Fertility intentions: Getting the right insights by asking the right questions. Population Reference Bureau, Policy Brief, 2018.

- Götmark, F. and M. Andersson, Human fertility in relation to education, economy, religion, contraception, and family planning programs. BMC Public Health, 2020. 20(1): p. 1-17.

- Sperling, G.B. and R. Winthrop, What works in girls’ education: Evidence for the world’s best investment. 2015: Brookings Institution Press.

- UNFPA, Investing in three transformative results: Realizing powerful returns. 2022: https://www.unfpa.org/publications/investing-three-transformative-results-realizing-powerful-returns.

- United Nations Development Programme. Gender inequality index. 2023; Available from: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematic-composite-indices/gender-inequality-index.

- Andrijevic, M., et al., Overcoming gender inequality for climate resilient development. Nature Communications, 2020. 11(1): p. 6261.

- Mueller, R., In Sahel: Family planning meets climate change. Yale Climate Connections, 2019.

- UNICEF. UNICEF data warehouse. 2023; Available from: https://data.unicef.org/dv_index/.

- UNEP, Emissions gap report 2022. 2022, United Nations Environment Programme: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2022.

- Project Drawdown. Drawdown solutions library. 2023; Available from: https://drawdown.org/solutions.

- Calma, J., Birth control and books can slow down climate change, in The Verge. 2020.

- Gillingham, K. and J.H. Stock, The cost of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2018. 32(4): p. 53-72.

- Wheeler, D. and D. Hammer, The economics of population policy for carbon emissions reduction in developing countries. Center for Global Development Working Paper, 2010(229).

- Coulson, J., V. Sharma, and H. Wen, Understanding the global dynamics of continuing unmet need for family planning and unintended pregnancy. China Population and Development Studies, 2023. 7(1): p. 1-14.

- UNFPA, Costing the three transformative results. 2019: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Transformative_results_journal_23-online.pdf.

- OECD. Official development assistance (ODA). 2023; Available from: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/official-development-assistance.htm.

- Wexler, A., J. Kates, and E. Lief, Donor government funding for family planning in 2021. 2022, Kaiser Family Foundation: https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/report/donor-government-funding-for-family-planning-in-2021/.

- Striessnig, E., W. Lutz, and A.G. Patt, Effects of educational attainment on climate risk vulnerability. Ecology and Society, 2013. 18(1).