Photo above: Daniel Lozano Valdes, Unsplash

Written and edited by Hannah Evans, MA, Population Connection, and Janet Larsen, Principal, One Planet Strategies LLC

Updated December 2025

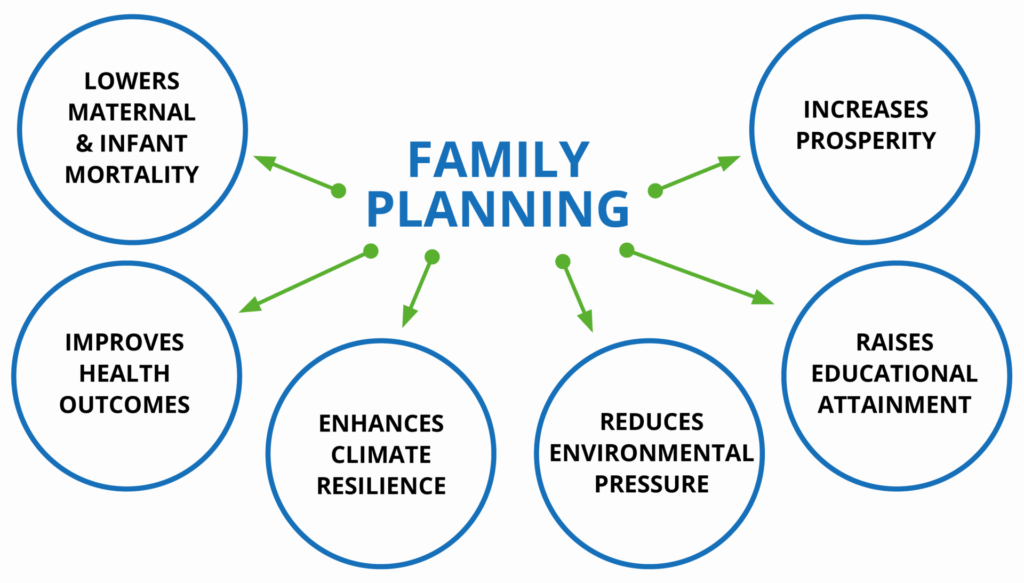

Abstract: Voluntary family planning is a human rights–based intervention that improves maternal and child health, expands educational and economic opportunities for women and girls, and reduces poverty. By slowing population growth, contraceptive use decreases pressure on natural resources and reduces future greenhouse gas emissions, making it an important yet often overlooked climate change mitigation solution. Integrating reproductive health services into climate and development strategies strengthens community resilience, especially in low-income countries facing rapid population growth and high climate vulnerability. Meeting the global unmet need for contraception is therefore both a critical health priority and a cost-effective climate solution.

Family Planning Enables People to Fight Climate Change

Access to family planning services is recognized internationally as a human right, as there are few rights more fundamental than the ability to choose whether, when, and with whom to have children. Expanding access to family planning services yields myriad social, economic, and environmental benefits. It also is vital for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, including for climate action [1]. Unfortunately, 259 million women worldwide have an unmet need for family planning.

Population growth and climate change are directly linked. Reproductive health and education play a role in climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. This is true because slowing population growth through rights-based investments in voluntary family planning services can reduce emissions and significantly increase individual, community, and national resilience in a changing climate.

Population Growth and Climate Vulnerability

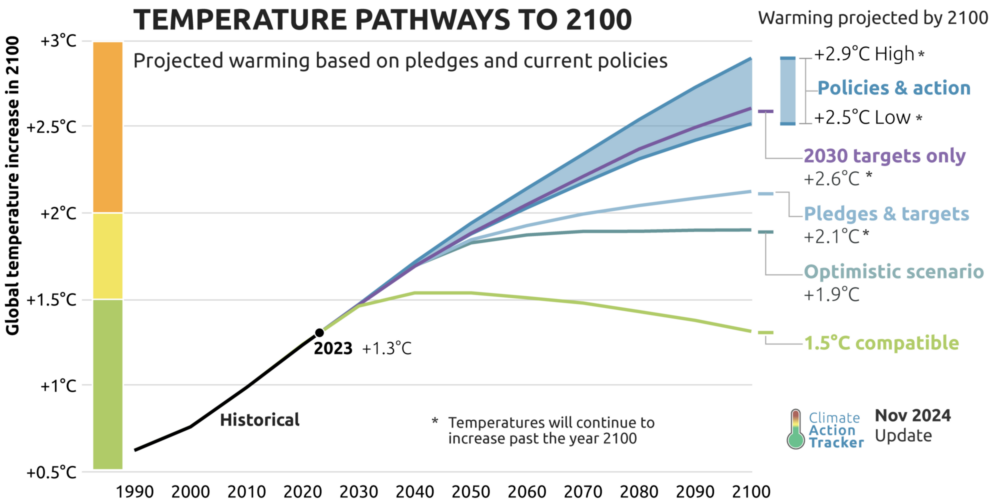

Population growth exacerbates the threats posed by climate change in a number of ways. Rapid population growth can lead to resource depletion, economic insecurity, and negative health outcomes, all of which make it harder for communities to adjust to a changing climate. Many countries experiencing rapid population growth are also those most affected by climate change impacts. The world’s low-income populations are especially vulnerable to population and climate pressures—both of which are expected to rise significantly in coming decades (see Figures 1 and 2) [3-5].

Figure 1

Figure 2

Climate change is the most threatening environmental crisis that humanity has ever faced. By burning fossil fuels and deforesting vast areas, humans have increased concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to levels unprecedented in at least 800,000 years [6]. As a result, the earth’s average temperature is rising, endangering food security, fresh water supply, and human health.

Rapid population growth compounds the negative impacts of climate change. For example, both population growth and climate change contribute to natural resource depletion, such as soil erosion, deforestation, and reduction of fresh water supplies. Growing demand for food can lead to conversion of forested areas to food production or intensified use of agricultural and pastoral lands for farming and grazing. As forests shrink, they become more vulnerable to climate change-related threats, such as wildfires, droughts, and pest outbreaks. When trees die and decompose, they release stored carbon to the atmosphere, further accelerating climate change [7].

People in low-income countries are among the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, despite their disproportionately small contribution to the problem. Due to geography, many of the world’s least developed countries are already prone to drought, flooding, and natural disasters. Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of such adverse weather events in many parts of the world [6]. Low-income populations have the least capacity to prepare for and respond to changing weather patterns, rising sea levels, and weather extremes. Additionally, the world’s poorest people are more likely to rely directly on natural resources for food security and livelihoods. They also have limited alternative employment opportunities and are less likely to have savings [8].

Climate change-induced disasters will lead people living in vulnerable situations to move. Climate refugees could cross national borders or move in-country in large-scale waves. The World Bank projects that without concerted action to slow climate change and bolster development, more than 143 million people in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America could be forced to leave their homes and migrate within their countries by 2050 as a result of crop failure, water scarcity, and sea level rise [9, 10]. Much of the coming migration will shift populations from rural to urban areas, further crowding cities.

Migration to large cities, which has already occurred in most high-income countries, is accelerating throughout the developing world, and will likely increase climate vulnerability. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes with very high confidence that “heat stress, extreme precipitation, inland and coastal flooding, landslides, air pollution, drought, and water scarcity pose risks in urban areas for people, assets, economies, and ecosystems” [11]. Within the context of sea level rise, more than a third of the world’s urban population lives within 100 kilometers (60 miles) of a shoreline, and two-thirds of the world’s largest cities are in low elevation coastal areas [12-14]. Urban areas’ impermeable surfaces and high population densities combine to put large numbers of people at risk from coastal and inland flooding and storm surge.

Additionally, many of the world’s key food producing areas are vulnerable to rising seas and other changes associated with global warming. Over 500 million people live within the world’s agriculturally productive river deltas, which are at risk from sea level rise [15]. For example, a 1-meter rise in sea level could submerge a third of the densely populated and fertile Nile River Delta [16, 17]. It would also put much of Bangladesh under water (see previous page) and inundate large areas of the low-lying Mekong Delta, where 90% of Vietnam’s rice is grown [15]. Agricultural yields also take a direct hit from the high temperatures and changing rainfall patterns associated with climate change. India and sub-Saharan Africa are two major regions expecting to add large numbers to populations while facing climate change-induced food productivity losses of 40% or greater by 2080 [18].

Bangladesh, an Illustration of Climate Vulnerability

In Bangladesh, climate change jeopardizes economic growth, environmental sustainability, and social progress. Bangladesh is geographically about the size of New York State, but its population of over 175 million is nearly nine times larger [19, 20]. Human numbers there have doubled over the past 45 years [19]. As the eighth most populous country in the world, Bangladesh is home to 2% of the global population, yet its annual carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions represent just 0.3% of the global total [19, 21].

Despite its negligible contribution to climate change, Bangladesh is especially at risk for climate impacts because of its low elevation, high population density, and precarious infrastructure [22]. Two-thirds of Bangladesh’s land area is less than 5 meters above sea level [23]. Already, the country is enduring the effects of rising seas, intense and irregular storms, cyclones, drought, erosion, landslides, and flooding [23-25]. Soil salinization from sea level rise is causing agricultural yield losses [26]. Most Bangladeshis live along the flood-vulnerable coast and in the low-lying fertile river delta [23, 25]. The meter-plus sea level rise anticipated this century could inundate vast tracts of land and lead upwards of 110 million people in Bangladesh to migrate to more hospitable locations [27].

Two-thirds of Bangladesh’s land area is less than 5 meters above sea level [9].

As dire as this sounds, without Bangladesh’s previous work to slow population growth, its predicament would be even worse. The country’s population is expected to surpass 226 million before peaking in 2071 (based on the UN’s medium-variant projection) [19]. Substantial government investments in reproductive health raised contraceptive prevalence nearly eightfold between 1975 and 2014, a jump from 8% to 62% [28]. Over the same time period, family size shrunk, with the total fertility rate (TFR) dropping from an average of 6.8 births per woman to 2.3 births per woman [19, 29]. Bangladesh also witnessed marked improvements in maternal and child health [30, 31].

Despite improvements in contraceptive prevalence, some 10% of Bangladeshi women of reproductive age still have an unmet need for family planning, meaning that they want to avoid pregnancy but are not using contraception [28]. The country continues to work with organizations such as Family Planning 2030 to develop and implement national action plans for family planning education and to reduce social and geographical disparities by increasing services and training providers [32]. Bangladesh’s success in slowing population growth will be an asset to climate adaptation efforts and overall resilience in that country.

Future Population Size Matters for Climate Change

The principal cause of climate change is the production of greenhouse gases from the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas. The IPCC has identified that the leading drivers of growth in global emissions are growth in economies and populations [33]. Greenhouse gas emissions—primarily carbon dioxide (CO2)—dramatically increased in the twentieth century and continue to hit record levels as the global population grows and industrializes [6].

The world’s largest contributors to climate change are the early industrializers: the United States, Russia, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Japan. Within recent decades, they have been joined by the world’s two most populous countries: China—now the world’s largest carbon emitter—and India [34]. Over the last decade, CO2 emissions have fallen in the United States and many European countries, even while economic growth has continued [34, 35].

Per person annual CO2 emissions currently are the highest in certain Middle Eastern oil producing countries, such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, and in automobile-dependent industrial economies like Australia, the United States, and Canada [34]. In contrast, lower-income countries, such as Bangladesh, Guatemala, and Uganda, have far lower per person emissions yet are endeavoring to industrialize their economies. Unfortunately, the conventional pathways of economic growth and human development involve processes that intensify climate change and put more people at risk for climate impacts.

The UN’s medium-variant projection from 2024 shows the global population reaching 8.6 billion in 2030, 9.7 billion in 2050, and 10.2 billion in 2070 [19]. This projection assumes that fertility falls in countries where large families are still widespread, based on shifts to smaller families that have occurred in other countries as incomes have risen. Historical data show that lower fertility follows many indicators of human development, including reduced child mortality, increased levels of education for girls, urbanization, growing labor force participation, and expanded access to reproductive health care services, including family planning [36].

Close to 6 billion people—75% of the world’s population—currently live in middle-income countries, many of which are rapidly industrializing [37]. As their economies continue to grow and integrate with global markets, increases in living standards and consumption will likely drive up the production of greenhouse gases.

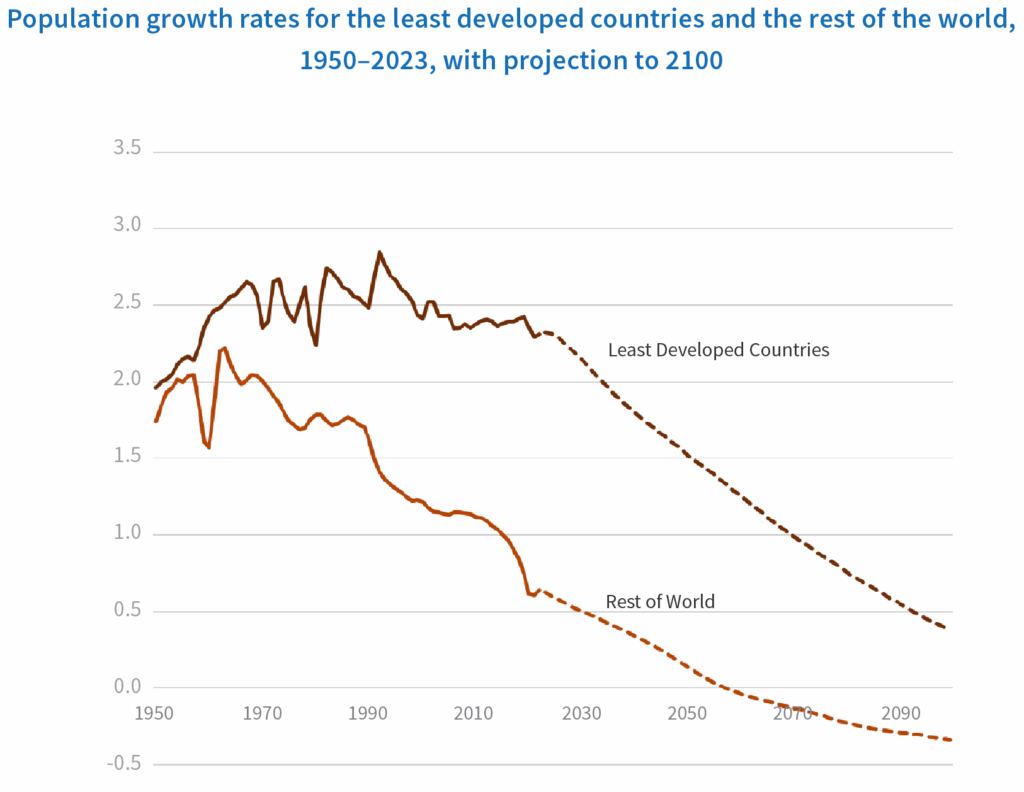

Meanwhile, rapid population growth continues to present challenges for sustainable development in most impoverished regions. The combined population of the 45 countries that the United Nations considers “least developed” is growing 3.8 times faster than the average for the rest of the world and is projected to double between 2025 and 2065 (see Figure 3) [19]. High fertility is positively correlated with extreme poverty: many of the fastest growing countries are also the poorest, with annual income per person averaging less than $1,000 (see Figure 4) [38]. Both conditions increase vulnerability to stresses associated with climate change.

Figure 3

In Uganda, for example, nearly 60% of people live in extreme poverty, earning less than $3 per day [39]. Over 73% of the country’s 51 million inhabitants are under the age of 30, and fertility rates remain high—averaging 4 births per woman—portending rapid future population growth. Uganda has maintained an annual growth rate near 3% for the past several decades, indicating population doubling roughly every 23 years. With the current growth rate of 2.7%, the country adds more than 1 million people each year [19].

The vast majority of Ugandans are small-scale or subsistence farmers who depend on rain-fed agriculture to survive [40]. In recent decades, Uganda has experienced major droughts, with more rain falling in extreme events rather than spread out over a season. This, along with an increase in the number of hot days and nights, makes farming more difficult and unpredictable [41]. With future warming projected, Uganda is likely to see more heat waves, droughts, and flooding, to the detriment of crop yields [42]. The country’s meager contribution to global CO2 emissions (0.01%) is disproportionate to the impact it faces: Uganda ranks among the countries most vulnerable and least prepared to face climate change [43, 44]. Population pressures together with large-scale deforestation, soil erosion, and climate impacts threaten to undermine the significant improvements in poverty eradication the country has achieved over the past several decades [45].

Figure 4

Family Planning and Sustainable Development

Climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts will be most effective when they recognize the links between poverty reduction, slower population growth, and environmental conservation. The clear association between high fertility rates and poverty signals the potential efficacy of voluntary family planning interventions to foster sustainable development. Meeting the global unmet need for family planning is a prime example of an integrated solution, as it holds substantial potential to reduce climate-warming emissions and mitigate climate impacts while protecting human rights. The benefits associated with providing women tools and information to control their fertility include environmental conservation, improved food security, decreased poverty, and heightened community resilience [46].

One significant outcome of enabling women to autonomously manage whether and when they become pregnant is increased educational attainment for women and girls [2, 47]. And because higher levels of education afford more options for formal employment and improved livelihoods, women with more education tend to have fewer and healthier children [48]. Better employment outcomes often lead to fewer children because higher incomes, education levels, and career opportunities improve access to family planning, delay family formation, and increase the real and opportunity costs of child-rearing. For example, a World Bank analysis on the relationship between fertility rates and education in Ethiopia concludes that girls receiving 12 years of education have four fewer children than their unschooled peers [49].

Meeting the global unmet need for family planning is a prime example of an integrated developmental solution.

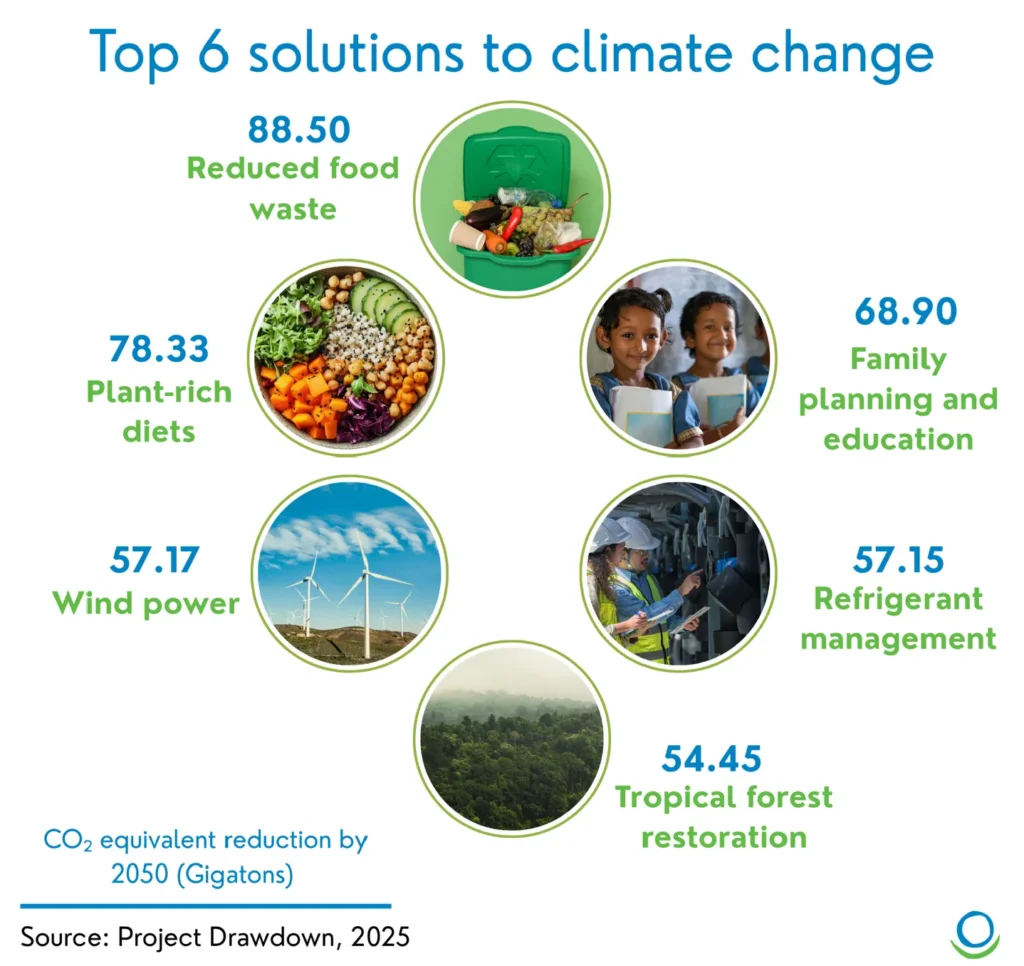

Reducing population growth also benefits the environment. It reduces demand for food, energy, and infrastructure thereby reducing pressures on local natural resources. Over time, slower population growth also reduces greenhouse gas emissions—so much so that access to voluntary family planning and universal high-quality education could avert 68.9 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions between 2020 and 2050 [50, 51]. Research from Project Drawdown shows that this is comparable in scale to emissions reductions associated with widespread development of wind power or from reducing food waste (see Figure 5) [51, 52].

The climate-warming emissions averted through investments in voluntary family planning programs are also inexpensive (about $4.50 per ton of CO2) in comparison to other options such capturing emissions from refrigerants (close to $11 per ton) or from new coal plants (at least $95 per ton), neither of which are guaranteed to last [18, 51, 53].

Figure 5

The positive and cross-sectoral impacts of family planning are vital for meeting the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030, particularly health (SDG 3), education (SDG 4), gender equality (SDG 5), and climate action (SDG 13) [1]. Slowing population growth through voluntary family planning services is increasingly being identified as a human rights-based and cost-effective component of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Reproductive Health and Family Planning Bolster Resilience to Climate Change

Including family planning and quality reproductive health care in community development strategies enhances resilience to climate change. Building resilience involves anticipating changes and developing capacity to allow social and ecological systems to “more readily recover from environmental change and shocks, avoid recurring crises, and develop sustainably” [54]. Ways that communities can bolster resilience to climate change include managing ecosystems, adopting adaptive governance practices, and developing natural disaster mitigation and response strategies [54]. Such approaches that recognize the connections among population dynamics, overall health, and environmental conservation are known as Population, Health, and Environment (PHE) approaches. Development efforts focused in areas such as food and water security and natural resource management could be improved by incorporating family planning and reproductive health care—a holistic PHE approach that ultimately enhances climate resilience.

Family planning improves the health of mothers and their children, which in turn augments climate resilience at the individual and population levels.

Family planning works to strengthen people’s ability to adapt to environmental changes and climate impacts. Family planning improves the health of mothers and their children, which in turn augments climate resilience at the individual and population levels. This is because good health is an important indicator of one’s ability to endure major environmental disturbances in both physical and psychological terms [54]. Additionally, family planning helps facilitate women’s empowerment and personal autonomy, which increases the likelihood of participation and engagement in climate adaptation efforts [55].

Furthermore, the smaller families resulting from avoided unintended pregnancies reduces the number of people at risk from climate impacts [55]. Recovery efforts are more manageable with fewer people needing assistance.

Filling the Family Planning Gap

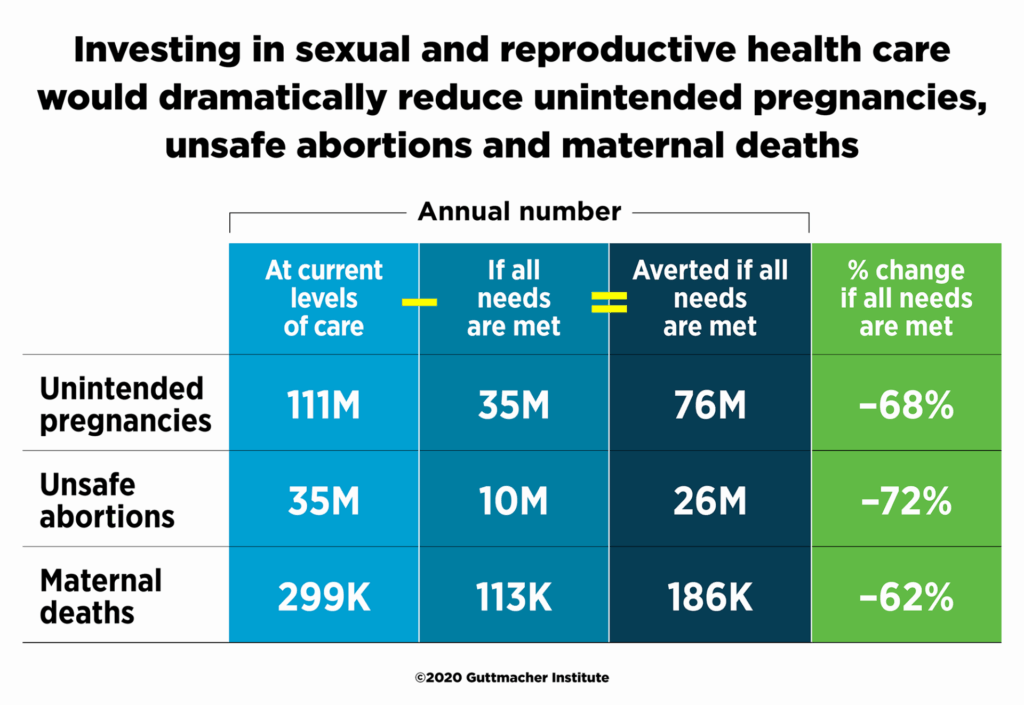

Worldwide, 259 million women have an unmet need for family planning. Of these, 214 million women in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) want to avoid pregnancy but are not using modern forms of contraception [2]. According to the Guttmacher Institute, there are 96 million unintended pregnancies in LMICs annually—almost half of all pregnancies in those countries. Meeting needs for contraception and quality reproductive health care services could prevent more than one-third of unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions, and nearly two-thirds of maternal deaths (see Figure 6) [2].

The estimated annual cost of meeting family planning needs in LMICs is $14 billion per year [2]. A total of $9.25 billion is already

being spent, leaving $4.8 billion still required to address unmet need. At the 1994 International Conference on Population and

Development held in Cairo, governments from around the world agreed to share the costs of this investment based on their relative wealth. The U.S. share of this bill would come to $1.7 billion

annually [56].

Funding family planning yields an impressive return on investment: Every dollar invested in providing sexual and reproductive health services and meeting the unmet need for contraception yields

$120 worth of other benefits [57]. Among such benefits are reduced poverty, improved health outcomes, increased economic opportunity, increased gender equality, enhanced climate resilience, and a more educated population of girls and women.

Expanding access to reproductive health care and family planning information and services helps women realize their right to control whether, when, and with whom they become pregnant. Meeting existing needs for reproductive health care would decrease poverty and improve health while slowing population growth—and therefore the growth of greenhouse gas emissions. Together these gains improve the capacity of individuals, communities, and countries to adapt to a changing climate.

Funding for reproductive health care, especially in low-income regions, is crucial both within the context of human rights and climate change mitigation and adaptation. Efforts to expand access to family planning and gender equity represent integrated solutions for sustainable development that should be included in broader strategies for low-carbon and climate-resilient development.

Sources available on PDF linked at top of page.