COVID-19: Pandemics and Population Growth

All any of us are reading about these days is the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. The Democratic Primary? Harry and Meghan ditching their royal crowns and moving to Canada? It truly…

Read More

Zoonotic diseases or zoonoses, infectious illnesses that spread between animals and humans, are closely linked to global population growth. All recent epidemics and pandemics, including COVID-19, Bird Flu (H5N1), Ebola, Zika virus, SARS, and West Nile virus were caused by zoonotic diseases. Animal-to-human viral spillovers are increasing because the growing human population is encroaching on wildlife habitats and exploiting wild and domesticated animals on a massive scale. Adding ever more humans and livestock to a finite planet, combined with increasing movement of people around the world, raises the risk of epidemics and pandemics.

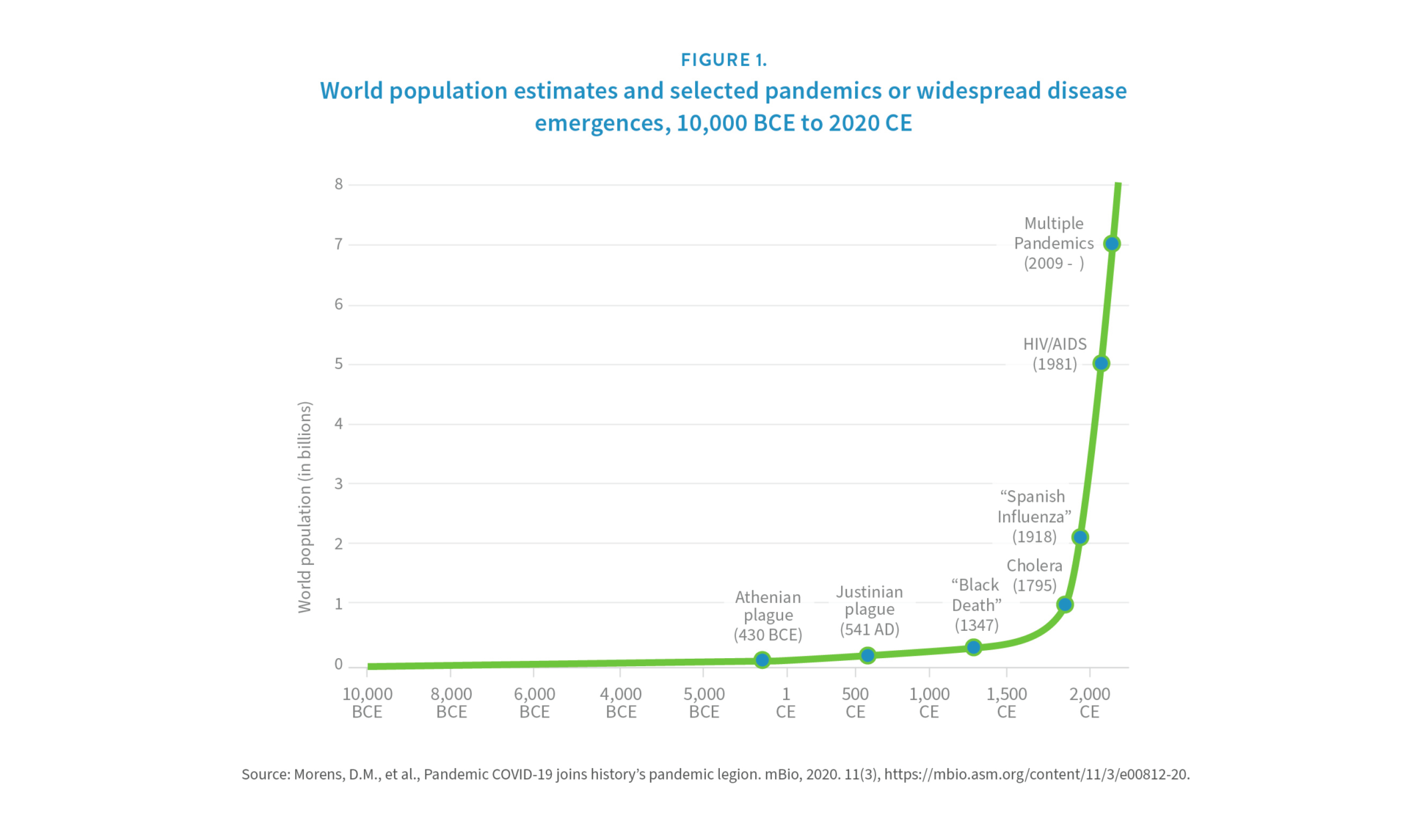

It took thousands of years for human numbers to reach 1 billion (in 1804) and just 218 more reach 8 billion (in 2022). Although the rate of growth is slowing, human population growth could continue into the next century, depending on fertility rates in the next few decades. The United Nations medium-fertility projection shows the global population increasing to 8.5 billion in 2030 and 9.7 billion in 2050, eventually peaking at 10.4 billion in the 2080s.

The human activities most likely to put people at risk of contracting zoonoses include intensive animal agriculture, habitat destruction (especially deforestation), bushmeat hunting, and the generation of greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change.

We already use almost half of all habitable land for agriculture, and most of this is used to feed and rear livestock. Growing human populations combined with increasing demand for meat and dairy drive habitat destruction such as deforestation, and human encroachment into wildlife habitats. This brings humans and their livestock into contact with wildlife and the diseases they harbor. Zoonotic diseases often pass to livestock before they infect humans.

Intensive animal agriculture is particularly risky as it forces animals to live in unnaturally high concentrations, in cramped and unsanitary conditions. Intensively reared livestock are often fed unsuitable, low quality food. All this leads to lowered immunity and frequent illness, which can quickly affect entire herds or flocks, creating a high risk of viral mutations that can infect farm workers and then spread to the rest of the population.

The wildlife trade, especially illegal poaching activities, presents a major threat to biodiversity and causes the emergence and spread of novel diseases. The COVID-19 pandemic is believed to have emerged in a wet market in Wuhan, China. Wet markets sell exotic animals imported from all over the world which are kept in unsanitary, extremely cramped conditions, and their unnatural proximity to each other makes it easy for viral diseases to spread.

In low-income countries, many people hunt and consume wild animals (known as bushmeat) for subsistence. Some wild animals, such as bats, have particularly high viral loads and are risky to eat. In addition, the risk of infection is high from animals that are genetically similar to us, such as great apes. Both HIV and Ebola have been traced back to the consumption of bushmeat. Low-income communities living near biodiversity hotspots are among some of the fastest growing populations, which presents a major threat to both nature and human health.

Climate change is making it easier for some infectious diseases to spread. Many areas are warming as a result of the climate crisis, which is expanding the range of disease vectors like mosquitos and ticks.

Until humans change the way we produce food and energy and how we treat animals, and until we end our unsustainable population growth, the threat of novel zoonotic diseases with epidemic- and pandemic-potential remains very high.

Decreasing our consumption of animal products is key, as are concerted efforts to fight climate change and the illegal wildlife trade. A stable, sustainable human population can be achieved by empowering women to take charge of their bodies and lives. Shifting mindsets to end the belief in human exceptionalism and treat nature and animals with more compassion is essential to achieving the changes we need.

We humans have pushed our way into all types of habitats, forcing interactions with wildlife that harm them and us; gathered up the exotic species that people will pay top dollar to eat and stacked them in cages to bleed and defecate on each other in wet markets; and farmed them in cruel, unsanitary conditions that allow livestock feces to find its way into our food and water.

Why are we pushing into wildlife habitats? Because we are driven to consume more space to build communities, more natural resources to sustain our lives and livelihoods, more wild game to feed more people. In short, because of rapid human population growth. Which is the same reason we’ve taken to farming livestock in such horrific conditions. We’re no longer eating meat produced at our local family-run farms. We’re eating meat that’s been factory farmed, sometimes thousands of miles away, in huge, depressing feedlots—because that’s the only way to produce enough of it for our massive population, which still grows by tens of millions of people a year.

Read the full issueThis resource explores the links between human activities and zoonotic disease emergence. The presentation slides use a case study from the Amazon rainforest to argue that population growth, intensified agriculture, habitat loss, wildlife trade, and climate change create the conditions necessary for viral animal-to-human spillover. Recognizing that human interaction with the natural environment must change in order to prevent the next pandemic, a One Health approach to land use and conservation is introduced as one potential solution.

This info brief explores the links between human activities and zoonosis—including global wildlife trade, intensified agriculture, habitat destruction, and deforestation—and highlights the role of integrated developmental approaches like One Health and Nature-based Solutions (NbS) in reducing the risk of new disease emergence and creating better health outcomes for people and the planet.